A New Lexicon For Countering Linguistic Subversion

British politicians have relied on loaded language to influence public perception on multiculturalism since the 1960s. The term 'ethnic minorities' subtly relativises the distinction between indigenous and non-indigenous populations, manipulatively steering the public debate.

Since the Second World War, and particularly since 1997, British politicians and others have sought to subvert the British people, that is, the English, Scots, and Welsh. This is done physically by mass immigration, and technically by legislation, but it is also achieved via cultural and psychological methods.

Cultural and psychological techniques include: telling schoolchildren Britain has always been multiracial; using black actors to play historic British characters on television; a black Dr Who; propagandising black footballers; the Windrush statue at Waterloo railway station; and portraying the transatlantic slave trade Britain’s founding event. All these examples act as grease on the physical and legal mechanics of demographic change.

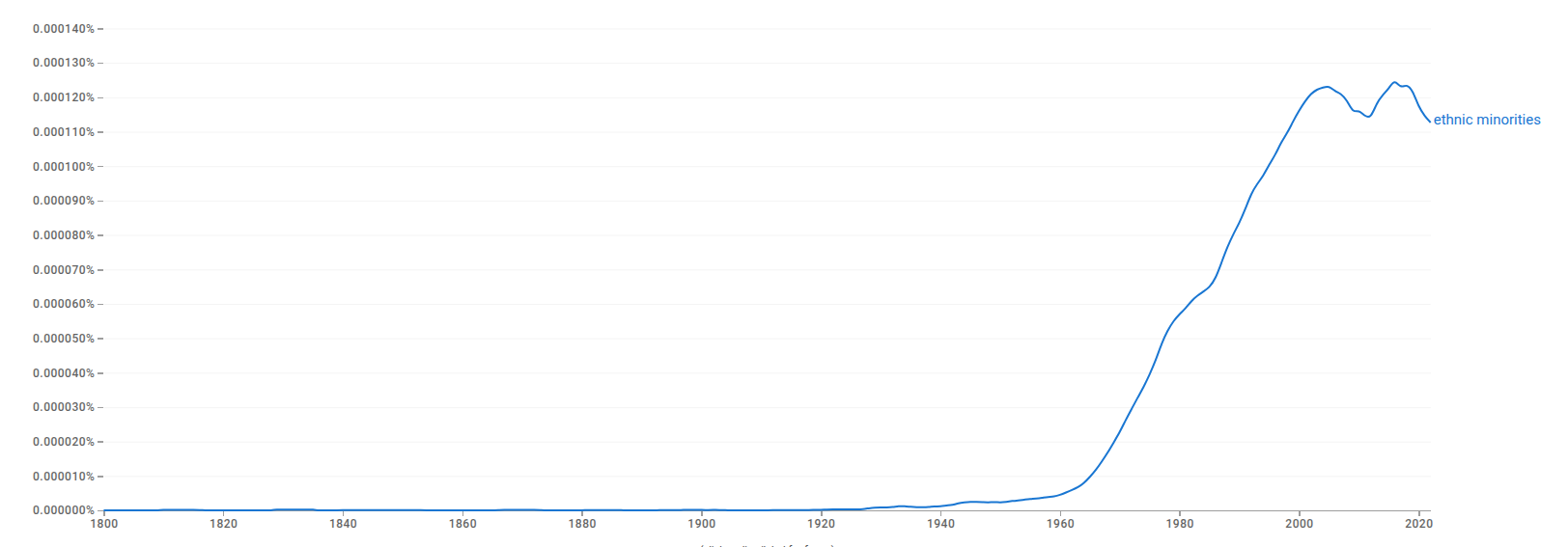

The most important of these psychological techniques, the one that is foundational to all others, is the term “ethnic minorities,” which first emerged in 1919 within Reform Advocate (Chicago), but entered the government lexicon in the late 1960s. The term “ethnic minorities” has become so pervasive that even people who are aware of Britain’s dismantling fall into the trap of using it. The term evolves constantly, usually due to the Civil Service, into absurdities like "BAME" to "Global Majority."

The problem is this: referring to foreign groups in Britain as “minorities” implies the difference between them and the host nation is merely numerical; i.e. an ethnic minority as opposed to the ethnic majority. The effect is to deny the true distinction between the two, which is indigenous/native and non-indigenous/non-native - or, for those who prefer a legal perspective, sovereign and non-sovereign.

The misuse of the term “ethnic minorities” can be illustrated by reference to early colonial America; nobody describes, then or now, English settlers in Massachusetts in the 17th century as an “ethnic minority”; they were English settlers and the various Indian tribes were native Americans.

In the British context, the English, Scottish, and Welsh, who founded the nations that carry their names, have constituted “the British” since the Acts of Union in 1707. Applying the term “ethnic minority” to foreign peoples who have arrived subsequently obscures the fact that these newcomers do not possess the same relationship to the modern state of Britain as the founding peoples, let alone to the nations of England, Scotland, and Wales

“Ethnic minority” is at best a non sequitur; at worst, it is a loaded or weaponised abstract term used to annul the founding population’s native status so foreign groups can be installed with equivalent status; in fact, immigrants are designated “ethnic minorities” as soon as they arrive. Elsewhere in the world, “minority” typically means an indigenous group, on their own historical land, but caught within a national boundary set by a larger group, often by way of conquest. In Britain, “minority” means the reverse: a non-native group whose settlement is facilitated by the State to change Britain’s population.

This is somewhat in keeping with Ferdinand de Saussure's notion of semiotics, and psychological literature which fallaciously promotes the doctrine language creates perception and thought; junk social science easily disproven by sign language and the deaf.

According to the 2021 census, approximately 18.3% of the population identifies with a non-white ethnic group: Indian (1.9 million, 3.1%); Pakistani (1.6 million, 2.7%); Black African (1.5 million, 2.5%); Bangladeshi (0.6 million, 1%); Black Caribbean (0.6 million, 1%); Chinese (0.4 million, 0.7%); Arab (0.3 million, 0.6%). 1.7 million people (2.9%) had mixed ethnicity, and 1.3 million people (2.1%) belonged to "other" ethnic groups.

Once the loaded nature of the term “ethnic minority” is understood, one can see any number of other terms which have a similar purpose and effect: “diversity,” “multiracial society,” ''multiculturalism," and “multicultural Britain” all imply the British people are just one component among others. Another term which is relevant is “decolonisation,” implying British society is occupied by British settlers, and so needs to be decolonised by "ethnic minorities"; this inverts the actual relationship, which is foreign settlers are colonising Britain.

The Greek root "di-" in both "divide" and "diversity" comes from the Greek prefix meaning "two" or "apart/asunder." In "divide," the word comes from Latin "dividere," which combines "di-" (apart) + "videre" (to separate). The root carries the sense of splitting something into two or more parts, separating what was once whole. In "diversity," the word derives from Latin "diversitas," from "diversus" meaning "turned in different directions." Here "di-" combines with "vertere" (to turn), literally meaning "turned apart" or "turned in different directions."

The common thread is the concept of separation or apartness - whether it's physically dividing something into pieces or describing things that are distinct from one another. Other English words with this same Greek root include "diverge," "divert," and "different," all carrying that fundamental meaning of separation or moving apart.

The opposite of diversity is "unity," or being joined together as one, or working together harmoniously. Diversity, equity, and inclusion has as its alternative, "unity, opportunity, and qualification."

The longstanding use of “ethnic minority” and its offshoots has brought about a corresponding replacement of the word “British” with “white British” or “white majority”. This affects public discourse, which feeds into policy and law; here are three examples:

- In November 2022, Nigel Farage tweeted “London, Manchester and Birmingham are now all minority white cities”, to which Conservative minister Savid Javid replied, “So what?” By referring to “minority white”, rather than “minority British” or “minority English”, Farage allowed opponents to assume there were black and brown Britons (i.e. people of non-British descent). Farage’s point could not be pressed home, because it was made at the expense of affirming who the British people are.

- In July 2025, Conservative MP Nick Timothy asked the government about the impact of MI6’s diversity policy on the recruitment of “white Britons”. The government replied intelligence agencies “must improve the diversity of their workforce in line with UK law [and] the Equality Act 2010 … Such action is considered lawful and includes … those from an ethnic minority background”. By framing his question as a matter of colour (“white Britons”), Nick Timothy steered the issue away from it being British people who are discriminated against; the government was thus able to respond in terms of racial inequality.

- In August 2025, Conservative MP Robert Jenrick wrote to the Law Society regarding its use of terms such as “minoritised ethnic” and “racially minoritised”. Jenrick said: “This guidance … seeks to divide people on the basis of race and ethnicity … It’s time to … reforge a society that is colour-blind and merit-based”. By seeking to curb the Law Society’s excesses, Jenrick made the mistake of validating the underlying notion British people should have no specific status or identity; indeed, that the population should be fluid.

Either the Conservatives and Reform do not understand the deconstructive effect of words like “white” and “ethnic minority”, or they are afraid of addressing the implication; the issue is not “racism”, “inequality” or “division”, but subversion, betrayal and treason.

A New Lexicon

To undo decades of mental channelling, a new lexicon is required that is clear, catchy, and accurate. It is the word British which needs to be recaptured most of all, more so than English and Scottish which are, to a certain extent, able to fend for themselves (although the same principles apply).

Although presently compromised, British can be properly clarified in the following ways: “native British”, “ethnic British”, “indigenous British”, “founding population”, “sovereign British”. These all avoid the trap of “white British” and “white majority”.

“Ancestral” is also useful, since it relates both to nation and family; everyone knows what a family ancestor is, and “ancestral” can extend this common understanding to the nation: the ancestral British. “Anglo-Celt” is accurate, but carries with it the risk of reducing the British to ethnic groups among others; the English, Scots, and Welsh should not lose their collective connection to the island of Britain.

The suitable term for foreigners, people born overseas, is exactly that; foreigners. For the foreign-descended population born in Britain, clarifying terms include: “non-native population”, “non-indigenous”, “non-sovereign”, etc. “Non-native British” is a non sequitur but safe to use, as it acknowledges the distinction between the politically-defined “British”, and the native and sovereign British.

A new vocabulary is likely to be met with questions like, “What do you mean by native British?” Unless asked in good faith, such questions should be closed down with a snappy response which does not waste time and energy. One possible method is to invert the word “diversity”; the native British are those prior to diversity; the post-diversity British are not the indigenous British. That forces bad-faith opponents to pretend they don’t know what diversity is, in which case, how do they justify wanting it?

By recapturing language, Restorationists can rescue people’s minds, and build a new cultural and psychological framework to convey correct understandings of nationhood and sovereignty.