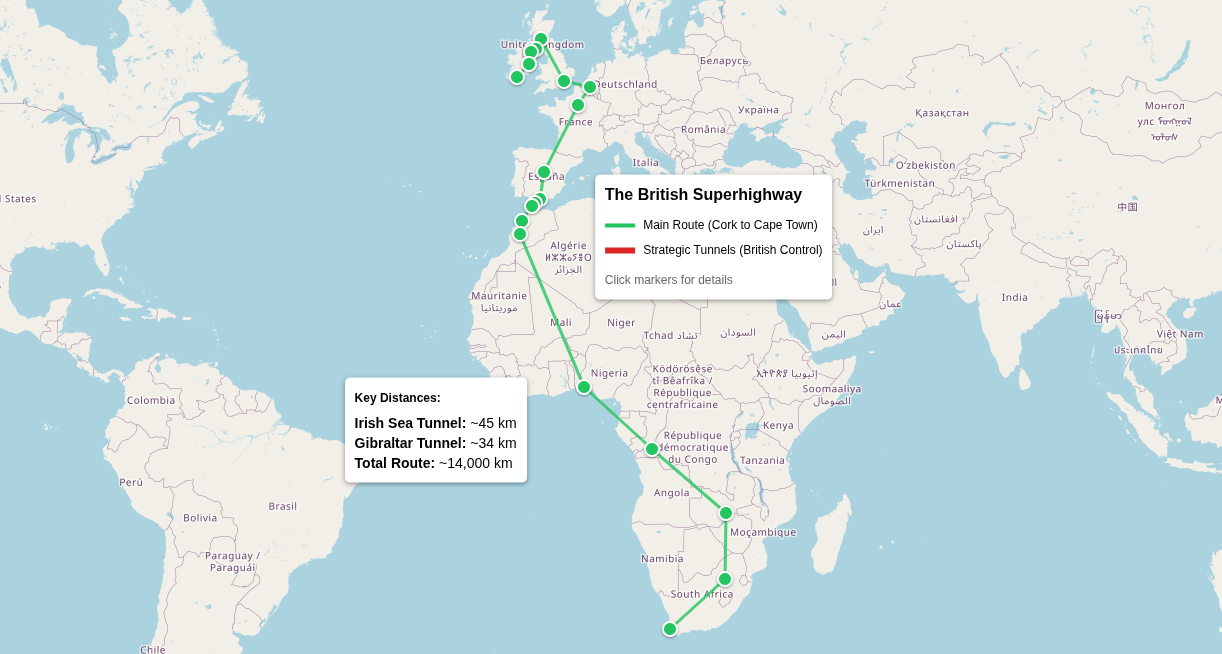

Cork To Cape Town: The British Superhighway

Building two underwater tunnels linking Northern Ireland to Scotland, then Gibraltar to Morocco, would give England strategic control of the trade across the Britannic Isles, Europe, and Africa. All for the annual price of a month's NHS spending. Whoever controls global trade commands world affairs.

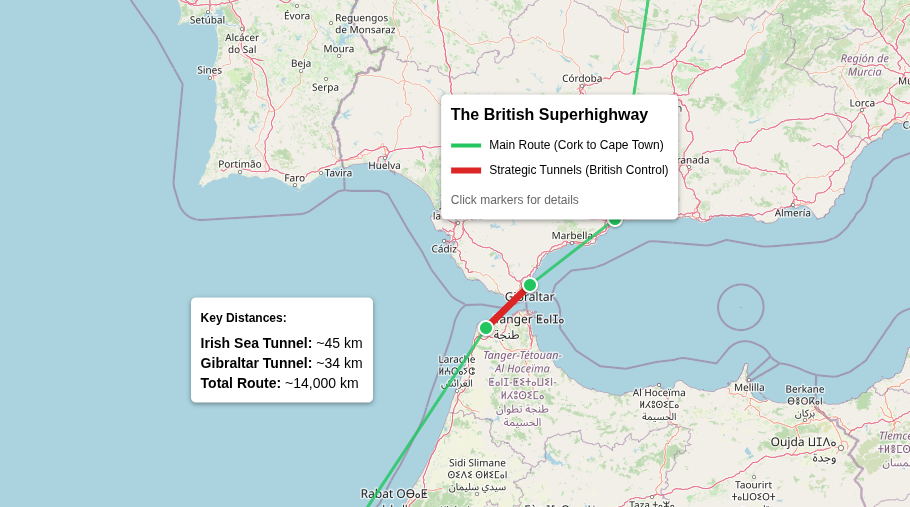

In an era when global trade determines national prosperity and geopolitical influence flows through commercial channels, Britain stands at the threshold of an unprecedented opportunity. The construction of two underwater tunnels—one beneath the Irish Sea connecting Northern Ireland to Scotland, and another under the Strait of Gibraltar linking the British territory to Morocco—would forge an unbroken transportation corridor from Cork to Cape Town. This ambitious infrastructure project would not merely represent an engineering triumph; it would restore Britain to its historical position as the indispensable intermediary of intercontinental commerce.

In 1904, Admiral John “Jackie” Fisher (1st Baron Fisher) made the observation there are five keys to the world:

Five keys lock up the world! Singapore, the Cape, Alexandria, Gibraltar, Dover. These five keys belong to England.

As the neck contains the carotid arteries and spinal cord to the brain, the world is controlled by chokepoints. It doesn't matter how large a military you have, if you can't get through the pass of Thermopylae. Britain does not need large swathes of land; it merely needs the carotid artery.

The strategic implications of such control cannot be overstated: as the Suez Canal transformed Egypt into the pivot point of Eastern trade and the Panama Canal made the United States the gatekeeper between two oceans, these twin tunnels would position Britain as the essential junction box of Euro-African commerce.

Every lorry carrying German machinery to Nigerian factories, every train hauling Congolese minerals to European refineries, every passenger seeking swift passage between continents would traverse British-controlled infrastructure. The nation would hold in its hands the power to facilitate or frustrate the economic ambitions of three continents.

The Imperial Chokepoints

The British Empire understood, perhaps better than any power in history, the extraordinary leverage conferred by controlling strategic chokepoints. The Rock of Gibraltar has stood as sentinel over Mediterranean commerce for three centuries under British rule. Singapore commanded the Strait of Malacca and with it the wealth of Southeast Asia. Hong Kong governed access to the Pearl River and China's vast markets. These were not mere territorial acquisitions but carefully selected pressure points where minimal geographic control yielded maximum strategic advantage.

The Suez Canal offers the most instructive parallel. When British forces secured the waterway in 1882, ostensibly to protect bondholders' interests, they acquired something far more valuable than financial returns.

Control of Suez meant control over the route to India, dominance of Eastern Mediterranean trade, and the ability to project naval power from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean without circumnavigating Africa. The canal became the jugular vein of empire, so vital Britain would wage war in 1956 rather than relinquish control. Though military adventure failed, it demonstrated the enduring truth: whoever controls the critical passages of global trade commands disproportionate influence over world affairs.

The proposed British Superhighway would replicate this dynamic on an even grander scale. Unlike Suez, which Britain controlled but did not build, or Panama, which lies beyond British reach, these tunnels would be British projects from inception to operation. The engineering expertise, the construction management, the operational protocols, the toll structures, the security arrangements—all would bear the imprint of British design and reflect British interests.

Engineering Colossus: The Technical Challenge

The sheer audacity of the engineering challenge rivals the greatest infrastructure achievements in human history. The November 2021 feasibility study commissioned by Sir Peter Hendy and undertaken by Douglas Oakervee, former chairman of HS2 and Crossrail, alongside Gordon Masterson of Jacobs Engineering, laid bare both the monumental scope and the tantalising possibility of these projects. The report confirmed what engineers have long suspected: while the technology exists to build both tunnels, they would represent the longest undersea passages ever constructed, dwarfing even the Channel Tunnel in complexity and scale.

Which is all the reason we need to do it.

The Irish Sea crossing presents a labyrinth of geological and historical obstacles. The North Channel plunges to depths of 300 metres along the proposed 45-kilometre route between Portpatrick and Larne. Unlike the relatively benign chalk marl through which the Channel Tunnel was bored, the Irish Sea floor consists of complex geological strata, including areas of unstable quaternary clay deposits. The seabed bears the scars of repeated glaciation, creating unpredictable variations in rock density and composition.

Engineers would need to navigate through basalt formations, sandstone layers, and metamorphic rocks, each requiring different tunnelling techniques and equipment. Good.

Yet geology represents only one dimension of the challenge. Beaufort's Dyke, the hundred-metre deep trench running along the most direct route, contains an estimated one million tonnes of unexploded ordnance dumped after both World Wars. Recent surveys by the British Geological Survey confirmed regular explosions from degrading munitions on the sea floor.

More alarmingly, a 2020 study by the UK & Ireland Nuclear Free Local Authorities revealed radioactive waste among the deposits, much of it "short-dumped" outside the dyke's boundaries, creating a contamination field of unknown extent. The Marine Accident Investigation Branch has documented near-collisions between submarines navigating these waters for testing and passenger ferries, highlighting the ongoing dangers.

The feasibility study proposed a hybrid approach: a combination of immersed tube sections for the shallower portions, traditional bored tunnels through stable rock formations, and potentially a partially bridged section incorporating artificial islands similar to the Øresund Bridge between Denmark and Sweden.

The contaminated zones around Beaufort's Dyke would necessitate either the world's largest maritime cleanup operation or revolutionary tunnelling techniques to pass safely beneath the contamination layer. Norwegian engineers have suggested adapting their floating tunnel technology, using 500-metre deep tension cables to suspend tunnel sections above the most problematic areas of seabed.

The Gibraltar crossing confronts different but equally formidable challenges. The Strait of Gibraltar marks the collision point between the European and African tectonic plates, with the Azores-Gibraltar Transform Fault running directly through the proposed tunnel route. This remains one of the most seismically active zones in the Mediterranean, with the potential for magnitude 7.0 earthquakes.

The tunnel would need to incorporate flexible joints and seismic dampeners capable of absorbing tectonic movements without compromising structural integrity.

At 300 metres below sea level along the Camarinal Sill route, the tunnel would need to withstand water pressures of 30 atmospheres. The current record holder, Norway's Ryfylke Tunnel, reaches only 291 metres below sea level. Even the Rogfast Tunnel, under construction and due for completion in 2029, will extend only to 392 metres.

The Gibraltar tunnel would operate at the very limits of current engineering capability, requiring new materials and construction techniques to ensure structural integrity under such extreme pressures. F**k yeah.

Spanish engineers who first proposed a tunnel in 1930 discovered another obstacle: the extraordinarily hard crystalline rock formations beneath the strait, which defeated the drilling technology of their era. Modern tunnel-boring machines would need to be specially designed with diamond-tipped cutting heads and enhanced cooling systems to penetrate these formations.

The machines themselves would need to be manufactured in sections and assembled on custom-built platforms at either end of the strait, as no existing vessel could transport fully assembled boring machines of the required 15-metre diameter.

The strait of Gibraltar funnels Atlantic storms into the Mediterranean, creating wind speeds exceeding 150 kilometres per hour. Construction platforms would need to withstand these conditions while maintaining the precision required for tunnel alignment.

The Irish Sea similarly experiences severe weather, with North Atlantic storms generating waves over 20 metres high. Construction windows would be limited to summer months, potentially extending the project timeline beyond the thirty years estimated in the feasibility study.

The Gibraltar tunnel would generate approximately 50 million cubic metres of spoil, enough to create an artificial island the size of Gibraltar itself. The Irish Sea tunnel would produce similar quantities. This material would need to be transported, processed, and either disposed of at sea in designated sites or repurposed for land reclamation projects.

The Architecture of Control

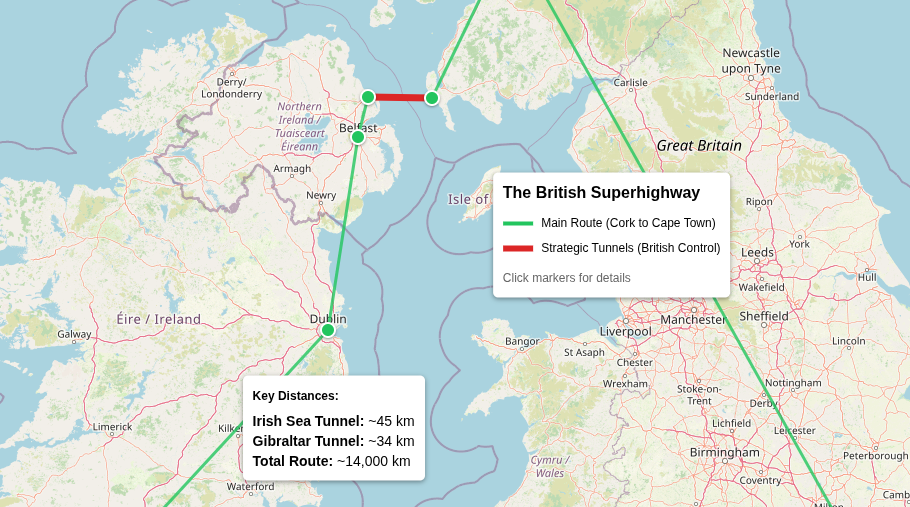

The Northern Channel tunnel, despite these challenges, would transform the relationship between Great Britain and Ireland while simultaneously binding both islands into a unified economic zone under de facto British coordination.

Currently, trade between Ireland and continental Europe must either traverse British roads or take lengthy sea routes around the British Isles. The tunnel would make the British route not merely convenient but essential, drawing Irish commerce inexorably through British infrastructure.

The 2021 feasibility study acknowledged the need for "very significant works" on both sides of the Irish Sea tunnel. The A75 road from Stranraer to the M74 would require complete reconstruction to motorway standards.

The single-track railway from Stranraer to Ayr would need electrification and expansion to accommodate high-speed rail.

On the Northern Irish side, new transport corridors would be carved from Larne to Belfast and onward to Dublin, creating an integrated high-speed network operating on British rail standards despite Ireland's broader gauge system. The solution would likely involve dual-gauge tracks or the Spanish Talgo-RD variable gauge system, but critically, the technical standards and operational protocols would be British.

The Spanish government's 2023 (EU-funded) commitment of €2.3 million for a joint design committee with Morocco signalled serious intent. The tunnel would connect directly to Spain's AVE high-speed rail network at Algeciras and to Morocco's new Al Boraq line, which already runs from Casablanca to Tangiers using the same gauge and electrification standards as the Spanish system.

This technical compatibility was no accident; it anticipates the tunnel's eventual construction and ensures both nations' dependence on maintaining operational consistency with British Gibraltar at the network's heart.

International Treaties and Legal Architecture

The Channel Tunnel provides the essential template for the legal framework governing these new passages. The Treaty of Canterbury, signed in 1986, established the binational governance structure while preserving national sovereignty. Each country retained jurisdiction over its half of the tunnel, with a jointly-owned operating company managing day-to-day operations. Critically, the treaty designated the tunnel as neutral territory for customs purposes while maintaining security controls at either end.

The Irish Sea tunnel would require a similar treaty between the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland, but with crucial differences reflecting Britain's stronger negotiating position.

Unlike the Channel Tunnel, where Britain and France entered as equals, Britain would provide the primary funding, expertise, and operational management for the Irish Sea crossing. The treaty could therefore establish British technical standards as mandatory, British security protocols as primary, and British commercial law as the governing framework for disputes.

The Gibraltar tunnel presents more complex treaty requirements, however – not least because of our pathetic government.

Britain would need to negotiate not only with Spain and Morocco but potentially with the European Union, given Spain's membership. The precedent of British Gibraltar's unique status—British territory with special arrangements for EU market access—provides a foundation.

The tunnel could be designated as an extension of Gibraltar's territory, placing it under British sovereignty while maintaining special customs arrangements for EU goods. Morocco, eager for enhanced European market access, would likely accept British operational control in exchange for preferential trade terms through the tunnel.

The treaty framework would need to address military passage rights, customs procedures, immigration controls, and emergency protocols. The Channel Tunnel explicitly prohibits military equipment transport except with special authorisation; similar restrictions would likely apply to both new tunnels.

However, Britain could negotiate exemptions for NATO operations through the Irish Sea tunnel and peacekeeping missions through Gibraltar, reinforcing its role as security guarantor for both passages.

The cleanup of Beaufort's Dyke alone would necessitate agreements on waste disposal, liability for historical contamination, and long-term monitoring. The Gibraltar tunnel would need provisions for protecting marine ecosystems, managing water flow between the Atlantic and Mediterranean, and preventing invasive species transfer.

Britain's leadership in drafting these protocols would establish British environmental standards as the baseline for intercontinental infrastructure.

Economic Leverage and Political Influence

When negotiations stall in Brussels, when African nations seek development partnerships, when Mediterranean countries require investment, Britain would possess unique leverage.

The ability to expedite or delay commercial traffic, to offer preferential rates to partners or impose punitive fees on rivals, to include or exclude nations from the prosperity flowing through these tunnels—these powers would restore to Britain the kind of "soft" coercion once exercised through naval supremacy.

The 2021 feasibility study, while absurdly concluding the projects were "impossible to justify" on purely economic grounds, acknowledged benefits the Treasury's narrow cost-benefit analysis could not capture. The creation of 35,000 jobs during construction represents only the beginning.

It's extraordinary these conclusions were reached given NHS spending.

British engineering firms would develop expertise applicable to underwater megaprojects worldwide. The expertise gained from conquering Beaufort's Dyke's contamination would position British firms as leaders in maritime environmental remediation.

The seismic engineering innovations required for Gibraltar would establish British standards for earthquake-resistant infrastructure globally.

The African Dimension

The Gibraltar tunnel's southern terminus in Morocco would position Britain as the primary European partner for African development. The 2023 joint Spanish-Moroccan committee's focus on connecting to the Al Boraq high-speed line reveals the transformative potential. This railway, Africa's first high-speed network, already links Morocco's Atlantic coast to the Mediterranean.

The tunnel would extend this network into Europe, with British Gibraltar as the mandatory transfer point.

The African Union's Programme for Infrastructure Development envisions transcontinental railways linking North Africa to sub-Saharan markets. The Maghreb-Europe Gas Pipeline already demonstrates the feasibility of fixed links across the strait.

A tunnel would accelerate these plans, creating a rail corridor from London to Lagos, from Edinburgh to Cape Town, all passing through British-controlled chokepoints.

Technological Sovereignty

The British Superhighway would establish British standards as the default for intercontinental infrastructure. The feasibility study emphasised the potential for the tunnels to carry more than just transport links.

Electrical interconnectors could transmit 5 gigawatts of power, enabling renewable energy trading between continents. Hydrogen pipelines could transport green fuel from African solar farms to European markets. Fibre optic cables could create dedicated data channels, positioning Britain as the digital gateway between continents.

Tidal turbines at tunnel mouths could harness the powerful currents flowing through both straits. The temperature differential between tunnel depths and surface waters could power geothermal systems. Solar panels on associated infrastructure and wind turbines on artificial islands could create energy-positive transport corridors. Britain would not just control the passages but the green energy flowing through them.

These utilities would require British approval for installation, British standards for operation, and British companies for maintenance.

Every additional cable or pipeline would deepen international dependence on British infrastructure. The tunnels would become not just transport corridors but multi-utility passages concentrating unprecedented technological control in British hands.

Countering Continental Rivals

The November 2021 feasibility study's publication coincided with growing concerns about Chinese infrastructure expansion through the Belt and Road Initiative. While the Treasury deemed the tunnels economically unjustifiable, the strategic calculus has evolved.

China's growing presence in African infrastructure development and its attempts to establish alternative trade routes bypassing traditional Western-controlled passages make British infrastructure investment not just advisable but essential.

The tunnels would offer African nations partnership without the debt-trap diplomacy characteristic of Chinese projects. British engineering standards, with their emphasis on safety, environmental protection, and worker rights, provide a compelling alternative to Chinese corner-cutting.

The common law legal framework, the English language advantage, and Britain's historical ties to Africa through the Commonwealth create natural complementarities Chinese competitors cannot match.

The Question of Will

The £335 billion estimated cost for bridges or £209 billion for tunnels represents a generational investment comparable to the Victorian railway boom or the post-war welfare state construction.

Yet spread over the – absurd – thirty-year construction period identified in the feasibility study, annual costs would amount to less than 1% of government expenditure.

The Treasury's conclusion that the cost was "impossible to justify" reflects orthodox economic thinking unsuited to infrastructure of imperial significance.

These two tunnels would cost the same as running the NHS for a single year, and give Britain unprecedented global power.

History demonstrates that great powers become great precisely by undertaking projects others deem impossible. The Victorians built railways across deserts where financial returns seemed doubtful. The Americans constructed the interstate highway system without clear economic justification. The Chinese are building Belt and Road infrastructure despite questionable commercial viability.

These nations understood what Britain's current leadership seemingly does not: infrastructure of strategic significance cannot be evaluated through conventional cost-benefit analysis.

The Imperial Restorationist Imperative

The engineering challenges are monumental but surmountable: exactly our type of thing. Beaufort's Dyke's million tonnes of munitions and radioactive waste can be cleared or bypassed. The Gibraltar fault zone's seismic risks can be managed through flexible engineering. The extreme depths can be conquered with new materials and methods. Norwegian engineers are already building deeper tunnels. Japanese engineers have spanned greater distances. The technology exists or can be developed; only political will remains absent.

The treaties can be negotiated, with the Channel Tunnel providing precedent and Gibraltar offering unique leverage. The engineering challenges can be overcome, with each solution adding to British technical supremacy. The economic benefits, while difficult to quantify in Treasury models, would compound over centuries of operation.

The nineteenth century belonged to Britain because Britain controlled the sea lanes. The twentieth century belonged to America because America controlled the financial systems.

The twenty-first century will belong to whoever controls the critical infrastructure of global commerce. The British Superhighway would position Britain to claim this role, transforming two tunnels into instruments of national revival.

The precedents are clear, the engineering is possible, the treaties have templates, and the strategic logic remains compelling. The only question remaining is whether Britain possesses sufficient imperial ambition to begin drilling.

We are Restorationists. We are Imperialists.

Of course the answer is yes.