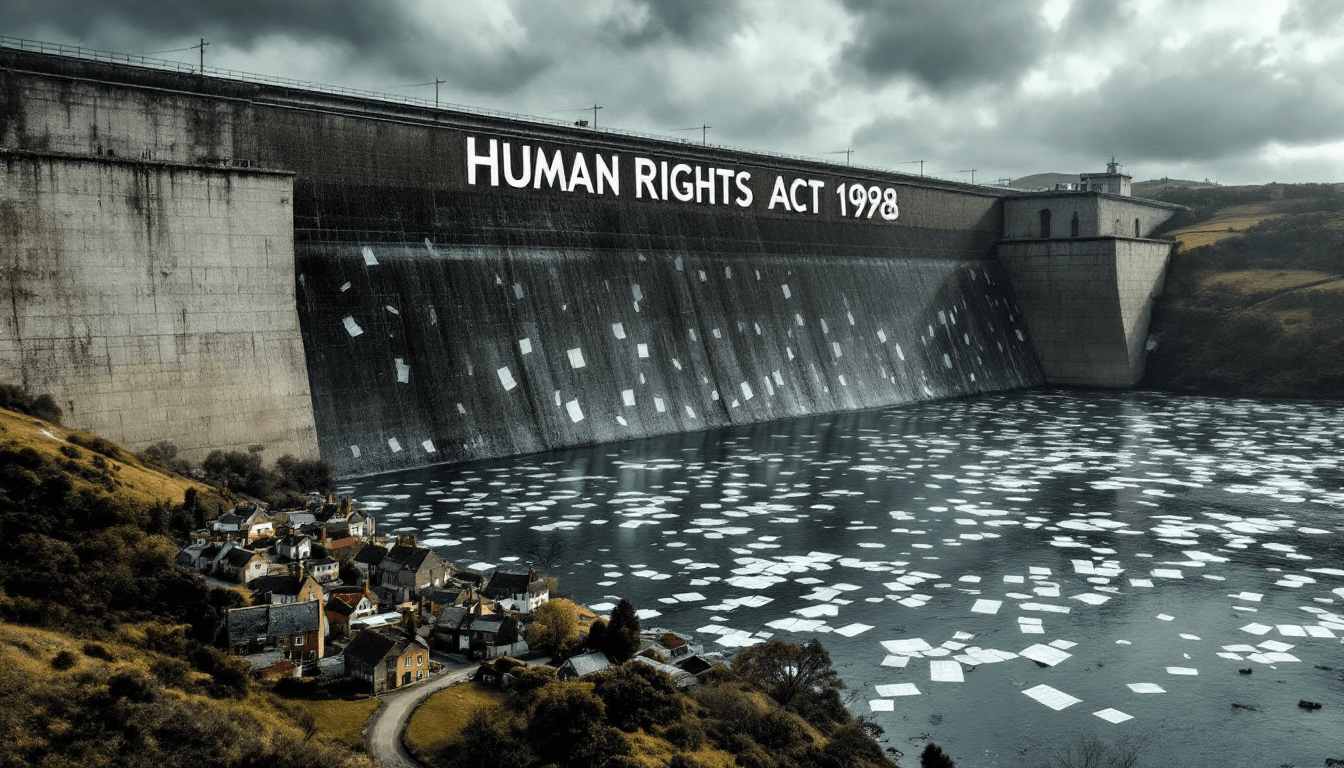

Dambusters Beware: The Devious Human Rights Act Trap

The HRA is a dam which cannot be destroyed without unleashing the floodwaters of New Labour’s quangoes and secondary legislation. The ECHR it entrenches is an ill-fitting garment which fails to protect liberty when it matters most, and a constitutional democracy cannot outsource its legitimacy.

The Human Rights Act of 1998 is not just a statute. It is a dam. Behind it lies the vast reservoir of New Labour’s reforms, the floodwaters of Blairite governance which have swollen over a quarter of a century.

The dam itself is solid concrete, constitutional in stature, deceptively permanent. Behind it, some three hundred and thirty tonnes of water – the legislation, the quangos, the secondary instruments drafted to widen their remit and multiply their cost – press against the structure. This water is not clear and sparkling but stagnant, thick with the malaise of bureaucratic accretions and institutional inertia.

Blair, in his political genius, understood to entrench the Human Rights Act was to entrench all which followed. To breach the dam is to risk the sudden release of the whole reservoir, cascading down the valley and drowning what remains of English liberty in the deluge. That was the true brilliance of Blair’s settlement: not the Act itself, but the way it secured the permanence of everything built behind it.

Successors who promised to repeal or replace the Act discovered too late that to do so was to endanger the entire edifice of post-1997 government. The dam cannot be destroyed without unleashing the flood.

We, the Restorationists, may play at being the dambusters – minus the questionably named dog – but unlike the originals we are not reckless in our charge. Compassion requires not explosion but drainage. The water must be siphoned carefully, deliberately, systematically.

Yet the sheer volume is daunting. No political party seems aware of how much has accumulated, and those who claim awareness in the civil service are either dissembling or paralysed, knowing that they have no plan to release it. The dam holds, the waters rise, and liberty waits downstream for the breach.

The European Convention on Human Rights has been sold to the British public as a bulwark against tyranny, a safety net for liberties, a noble post-war guarantee that the atrocities of the twentieth century would not be repeated. The reality, as it has evolved, is stranger and less reassuring. It is a system born of inter-state arbitration, refashioned by Strasbourg into a quasi-federal court for half a continent, imported into British law by Tony Blair’s government in the form of the Human Rights Act, and subsequently entrenched not by popular consent but by PR, trade deals, and the convenience of governments reluctant to confront it. It is less a charter of liberty than a political straitjacket.

The myth at the heart of the ECHR is that it was conceived as a guardian of the individual against the state. In truth, its founders imagined a mechanism for avoiding war through binding arbitration between states.

It was not until Harold Wilson’s government accepted the right of individual petition in 1966 Strasbourg began to resemble a court for citizens rather than governments. The subsequent transformation into a supra-constitutional tribunal, sitting over forty-seven states and some 820 million people, was not anticipated at its creation.

The expansion of membership after 1989 and the adoption of the doctrine that the Convention is a “living instrument” turned an inter-governmental project into a judicial leviathan. Lord Hoffman once observed the right of individual petition enabled the Court to intervene in the details and nuances of domestic law. He might have added that it created the conditions for permanent mission creep.

The Human Rights Act of 1998 compounded this trajectory. Presented by "New Labour" as “bringing rights home”, it was in reality a method of offloading Strasbourg’s caseload onto British judges while advertising constitutional modernity. Blair’s government wrapped the Act in the language of patriotism, invoking Churchill as a founder of the Convention, while ensuring that an international treaty drafted in the aftermath of Nuremberg became a domestic statute of near-constitutional force.

It gave judges a novel interpretive duty to construe all legislation in a manner compatible with the Convention “so far as possible”. In practice this meant courts stretching and reshaping parliamentary language to satisfy Strasbourg’s jurisprudence, with declarations of incompatibility issued where this could not be done. What was sold as a limit on European interference became the conduit for it.

The public perception of the Act quickly diverged from its legal operation. Newspapers railed against it as a villains’ charter, highlighting cases where deportations were blocked on Article 8 family life grounds. The irony is the Act proved most potent not in protecting unpopular minorities but in enabling government.

During the coronavirus pandemic, it was the HRA that furnished the legal justification for the suspension of ordinary life. Article 2’s guarantee of the right to life was invoked as the state’s positive duty to lock down an entire population. Rather than derogate under Article 15, the government relied on public health exceptions to curtail liberty. This was not incidental: derogation would have admitted openly rights were being suspended, synchronising Britain with authoritarian states which had done the same. Better to present the suspension of liberty as compatible with the Act itself. Thus the HRA became the cloak of legality for one of the most sweeping exercises of state power in modern British history.

Challenges were predictably futile. In Dolan, the Court of Appeal held the March Regulations restricting movement did not constitute a deprivation of liberty under Article 5. Vague phrases such as “reasonable excuse” were deemed adequate to reconcile the measures with the Act. The cost of judicial review, borne by private citizens at great personal expense, ensured the test of compatibility was academic.

As Robert Buckland implied when Justice Secretary, police had enforced measures beyond what most considered reasonable, yet the HRA proved no obstacle. What emerged from this period was a lesson in the unreliability of rights culture: rights are available when not desired, and unavailable when most needed.

Brexit was supposed to be the moment of rupture. The rhetoric of “taking back control” rested on ending the jurisdiction of foreign courts. Yet the ECHR was never severed. Successive Conservative manifestos flirted with repeal of the Human Rights Act and its replacement with a British Bill of Rights, but the proposals evaporated under pressure from coalition partners, trade negotiators, and devolution settlements.

The EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement contains vague provisions on respect for international human rights obligations, leaving open the possibility of trade repercussions should Britain withdraw from the Convention. The Good Friday Agreement, meanwhile, relies on incorporation of the ECHR into Northern Irish law. Devolved governments in Scotland and Wales have embedded it into their legal orders.

The effect is a constitutional knot: withdrawal threatens not only external trade but internal stability.

The Human Rights Act is formally a constitutional statute, immune from implied repeal. More powerfully, it is entrenched by name. To repeal something called the "Human Rights Act" is to invite accusations of authoritarianism, whatever the content. Governments are reluctant to expend capital on explaining the distinction between rights in principle and the machinery of Strasbourg jurisprudence. Easier to tinker at the edges and to promise reform at some future juncture. The result is paralysis.

Into this paralysis steps Keir Starmer. His government presents itself as the antidote to chaos, pragmatic, unburdened by doctrine. Starmer himself is a former human rights lawyer, knighted for services to law, steeped in the jurisprudence of the Convention. For him the ECHR is both professional inheritance and political armour.

His Attorney General, Richard Hermer, describes it as a source of national pride. Justice Secretary Shabana Mahmood insists it must evolve but not be abandoned. Yvette Cooper tightens family reunion rules under Article 8 while affirming Britain’s commitment to Strasbourg. The message is consistent: reform, not rupture. Starmer impersonates competence by embracing the very framework his opponents blame for national weakness.

Yet the electoral picture tells another story. Starmer’s majority of 411 seats is less a mandate than a consequence of Reform UK’s insurgency. With 4.1 million votes and five seats, Farage’s party siphoned off the Conservatives’ base. Their platform, openly advocating withdrawal from the ECHR to control immigration, was the one issue on which they were more credible than the government they undermined. The Conservatives bled votes across the North and Midlands, not to Labour but to Reform, and the result was Labour’s landslide.

Starmer governs by default. His silence on the ECHR during the campaign concealed a fragile consensus: he knows touching it risks detonating the Union, yet leaving it untouched feeds the cynicism of voters convinced that Britain cannot control its borders while bound by Strasbourg.

This cynicism is not without basis. The number of deportations actually blocked by the Court is vanishingly small, yet the perception is of systemic obstruction. Media spin conflates Strasbourg with Brussels, human rights with migration, judicial review with political sabotage. Academics note the distortion, but perception is political reality.

The paradox is stark: the Convention is simultaneously invoked to justify the lockdown of an entire nation and blamed for preventing the deportation of a handful of criminals. In both cases its operation is opaque, its legitimacy fragile, its reputation poor.

The case against the ECHR, then, is not that it protects rights too jealously but it protects them unpredictably and without consent.

It was never designed to bear the weight it now carries. It has mutated into a federal court without a federation, handing down rulings that override parliamentary settlement, staffed in part by judges from states that are not themselves fully free. Its jurisprudence stretches the Convention to cover issues far from the horrors of the mid-twentieth century. Its domestic incarnation, the HRA, has entrenched judicial power without securing popular support. It is a gown cut in Strasbourg and forced to fit British shoulders.

The lesson of the past quarter century is that this gown does not fit. It constrains governments from acting decisively where they have democratic mandates, yet permits them to trample liberties when expedient. It entrenches judicial authority without democratic legitimacy. It ties Britain’s constitutional order to settlements in Northern Ireland and Scotland which render reform perilous. It hangs over trade relations with the EU. Above all, it leaves the electorate convinced their votes do not matter where courts intervene.

To continue on this path is to accept permanent incoherence. Starmer may impersonate stability by pledging fidelity to Strasbourg, but this stability is fragile and dependent on voters not asking too many questions. Reform UK will continue to provide an outlet for those who do. The Conservatives, if they are to revive, must decide whether to fill the vacuum or to surrender it. Either way, the ECHR will remain the faultline of British politics until it is confronted honestly.

Britain is not obliged to reject human rights. It is obliged to determine how they are to be protected and by whom. The HRA and the ECHR have become confused with the substance of rights themselves. They are mechanisms, not ends. If they frustrate the will of Parliament without providing real protection to citizens, they deserve scrutiny. If they have become so entangled in devolved settlements and trade agreements they cannot be reformed, they deserve challenge. A constitutional democracy cannot outsource its legitimacy to a court in Strasbourg.

The time has come to cut a new garment.

Richard Moryson once advised English lawyers, after the break with Rome, to act as tailors making an English gown out of Italian velvet. Britain must do the same with human rights law. It must design a framework that reflects its own traditions, that balances liberty with security, and that commands genuine popular consent. To continue wearing Strasbourg’s ill-fitting suit is to invite permanent disillusion.

The case against the ECHR is not only legal or political. It is existential. A nation that cannot clothe itself in laws of its own making is a nation already half undressed.