Gatehouses And Englishness: Reclaiming Tudor Architecture In The Academic Canon

Tudor gatehouses represent a distinctly English architectural language unfairly ignored by classical scholarship. Featuring portcullis symbols and heraldic decoration, gatehouses evolved from defence to ceremony while maintaining cultural continuity from Anglo-Saxon times, to Parliament.

In the scholarly dialogue surrounding architecture, the English Tudor period has often been portrayed as an eccentric outlier, a whimsical deviation from the so-called correct classical tradition. Yet this view obscures a more nuanced and profound truth: Tudor architecture, particularly its most consistent and symbolically potent form, the gatehouse, represents a distinctly English architectural language. This language, emerging long before the introduction of the term "architecture" into the English lexicon, speaks to a deeper national identity. The Tudor gatehouse should be rescued from academic dismissal and insert into its true role as a cornerstone of Englishness.

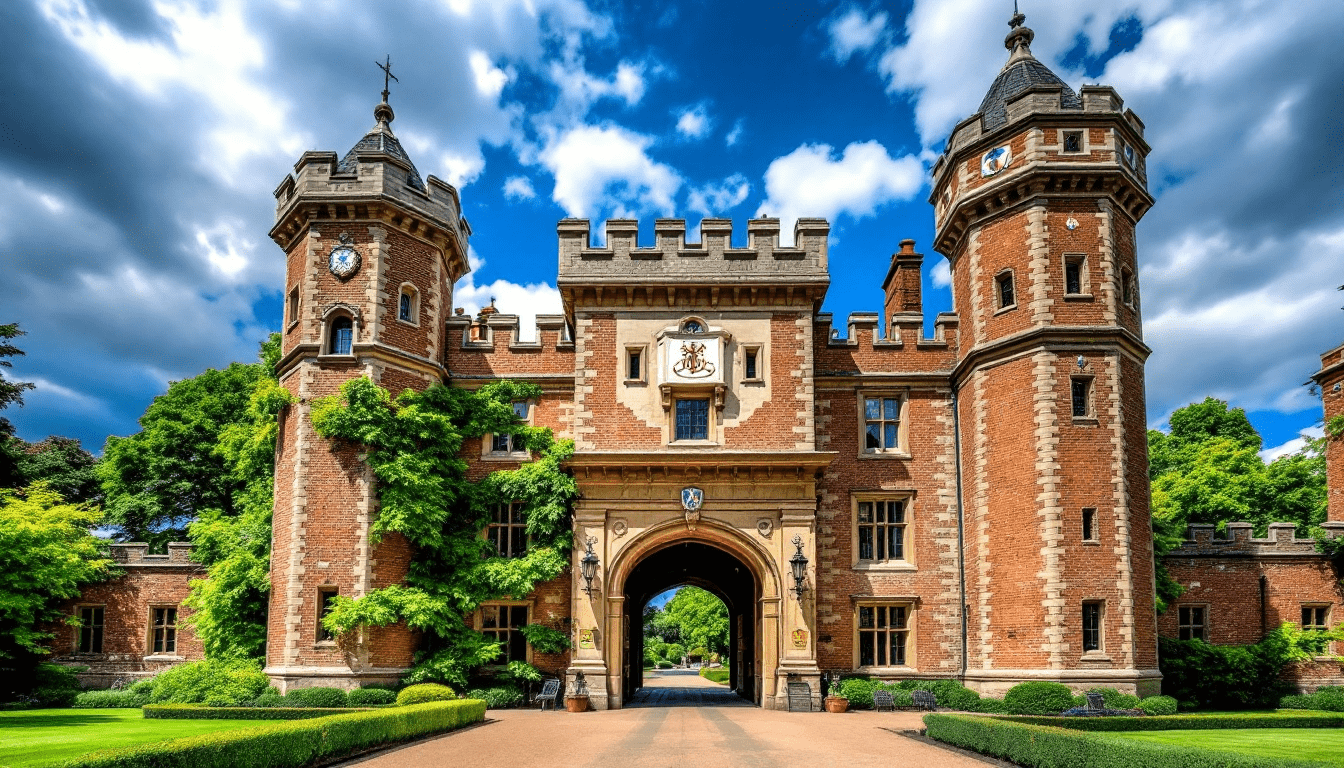

The Tudor gatehouse, with its rectangular massing, octagonal turrets, crenellated parapets, and multiple stories, prefigured the aesthetic and symbolic expressions of power in early modern England. While the term "architecture" entered English usage only in the sixteenth century through John Shute's Italianate travels, building in England had long operated through masonic traditions and pattern books. These traditions preserved forms like the gatehouse, evolving from Anglo-Saxon burh-geats to Norman stone fortifications, through to ecclesiastical appropriations at Battle Abbey, and finally into the courtier-houses of Henry VIII's reign.

This architectural continuity was not simply a result of insular conservatism but an intentional resistance to continental modes. George Chapman's lament over the "barbarisme" of English building reflects more a classical bias than an objective critique. For early modern England, Rome was not a cultural aspiration but an obstacle, especially after Henry VIII's break with the Papacy. Thus, the Tudor gatehouse can be read not merely as a feudal remnant but as a visual assertion of English sovereignty, embodied most clearly in its use of the portcullis, the Tudor badge.

Indeed, the gatehouse became a physical manifestation of loyalty, embodying David Starkey's notion of bastard feudalism wherein the royal household extended itself into noble households through architectural patronage. Gatehouses proliferated during Henry VIII's reign, becoming standard elements in newly ennobled or court-favoured estates. This is perhaps best exemplified in the license to crenellate; royal consent was required to create the appearance of battlements (crenellations) on a household, or frequently, on a gatehouse. These were more than fashionable structures; they were spatial declarations of allegiance, often forming an H-shaped silhouette, arguably referencing Henry himself, much as the Elizabethan E-shaped plan paid symbolic homage later would to his daughter. The connection between architectural form and dynastic identity was unmistakable. The portcullis was not merely symbolic inherited from Margaret Beaufort (Henry's grandmother and foundress of St John's college) but was reified in masonry in the elaborate gates of the time, heralding the power of the Crown and its agents across the realm.

This development followed a clear transition from functional military architecture to symbolic and ceremonial design. Tattershall Castle, begun in the 1430s by Ralph Cromwell, exemplifies this shift. Constructed predominantly in brick, a material ill-suited to serious military defense in the emerging era of canon, Tattershall features a towering central structure that maintains the appearance of earlier castle-keeps, yet functions as a comfortable residence. Through the 16th century, machicolations and turrets, while evoking medieval fortification, served little purpose in practical defence, and often hide an inaccessible pitched roof – as at St John's and Trinity Colleges in Cambridge. They are best understood as aesthetic choices—a castle in fancy-dress. Similarly, Layer Marney Tower and Cowdray House adopted the visual language of fortresses while serving purely domestic roles. These structures reflect a broader cultural trend in which the image of martial strength was maintained for symbolic purposes, especially as a signifier of status and allegiance in the Tudor court.

Heraldic decoration played a key role in reinforcing the ideological power of the gatehouse. The portcullis, originally a badge of the Beaufort family was adopted as a state symobol by the Tudors, came to represent both dynastic legitimacy and national continuity. Unlike coat armour, which was exclusive to individuals, heraldic badges like the portcullis could be disseminated and displayed broadly. They were affixed to buildings, embroidered on uniforms, and carved into stone, thereby transforming the physical landscape into a heraldic tableau. This heraldic language was not merely decorative but functioned as a semiotic system, encoding messages of loyalty, authority, and service.

Moreover, the gatehouse became a threshold not just between public and private, but between the realm of the governed and the symbolic body of the monarch. Sir Thomas Smith’s observation noble households functioned as extensions of the King’s own body finds architectural expression in the gatehouse. It marked the boundary of a loyal subject’s estate, yet visually declared that estate as an outpost of the King’s own person. This metaphysical extension of royal authority would eventually be institutionalised in the form of Parliament.

By the nineteenth century, the design for the new Palace of Westminster incorporated the portcullis into its iconography. While the competition was officially won by Charles Barry, it was Augustus Pugin who is often credited with its appearance. Pugin, a staunch advocate of Gothic revival and a devout Catholic, infused the building with Tudor motifs, including the portcullis. The style is distinctly English, tudor and perpendicular, but according to commentary at the time Barry appears to have had the greater influence. Displeased with the exterior appearance, Pugin is said to have remarked 'All Grecian, sir; Tudor details on a classic body.' Pugin for one regarded the Tudor style not as anachronism but as the embodiment of English national character. His work transformed the portcullis from a dynastic badge into a constitutional symbol.

Today, the portcullis remains the emblem of the Houses of Parliament. This continuity demonstrates the architectural language of the Tudors did not vanish but was transmuted into the iconography of the modern state. From the turrets of collegiate gatehouses to the heraldic symbols on parliamentary letterheads, Tudor architecture has shaped the visual and ideological grammar of English governance. Its legacy is not only aesthetic but constitutional, embedding monarchical symbolism into the very fabric of democratic institutions.

In a time when English building lacked the classical terminology of Vitruvian treatises, the gatehouse stood as a uniquely English form of architectural rhetoric. It was deliberate and legible to its audience, much like heraldry, and it persisted through Tudor, Elizabethan, and even neo-Tudor revivals into the digital age. In online realms like the game RuneScape, designed by Cambridge-educated developers, the Tudor gatehouse persists as a globally recognisable signifier of Englishness and chivalric nostalgia. In these instances, architectural language transcends bricks and mortar and becomes embedded in the cultural imagination.

The significance of the gatehouse extends beyond aesthetics or symbolism. It functioned as a threshold, a physical and ideological boundary between the private and the public, the familiar and the foreign. Its form, consistent over centuries, speaks to a collective memory rooted in Anglo-Saxon tradition and perpetuated through successive architectural expressions. The very recurrence of this form attests to its embeddedness in English identity. It was not a mere stylistic choice but a deliberate invocation of continuity, a visual anchor in times of dynastic change and national transformation.

The academic exclusion of Tudor architecture from the architectural canon, hinging on its supposed deviation from classical norms, is not merely a disciplinary oversight but a form of cultural gatekeeping. By redefining what constitutes "architecture" and acknowledging the gatehouse's historical continuity, symbolic potency, and enduring relevance, we can restore Englishness to its rightful place in architectural history. This restoration is not an act of nostalgia but of critical recognition. The Tudor gatehouse is not a peripheral curiosity but a central chapter in the architectural narrative of England, a chapter that demands scholarly attention and cultural respect. My survey text on the gatehouse can be found here.