Hate Club: A Bloodstained Autopsy Of The Radical Left And Right

Caught between junkie messiahs, violent zealots, and a media desperate for monsters; from slick studio shoots to coke-fuelled afterparties, from rallies to vicious rifts. Idealism can curdle into corruption, and those who claim to fight hate often feed it the most.

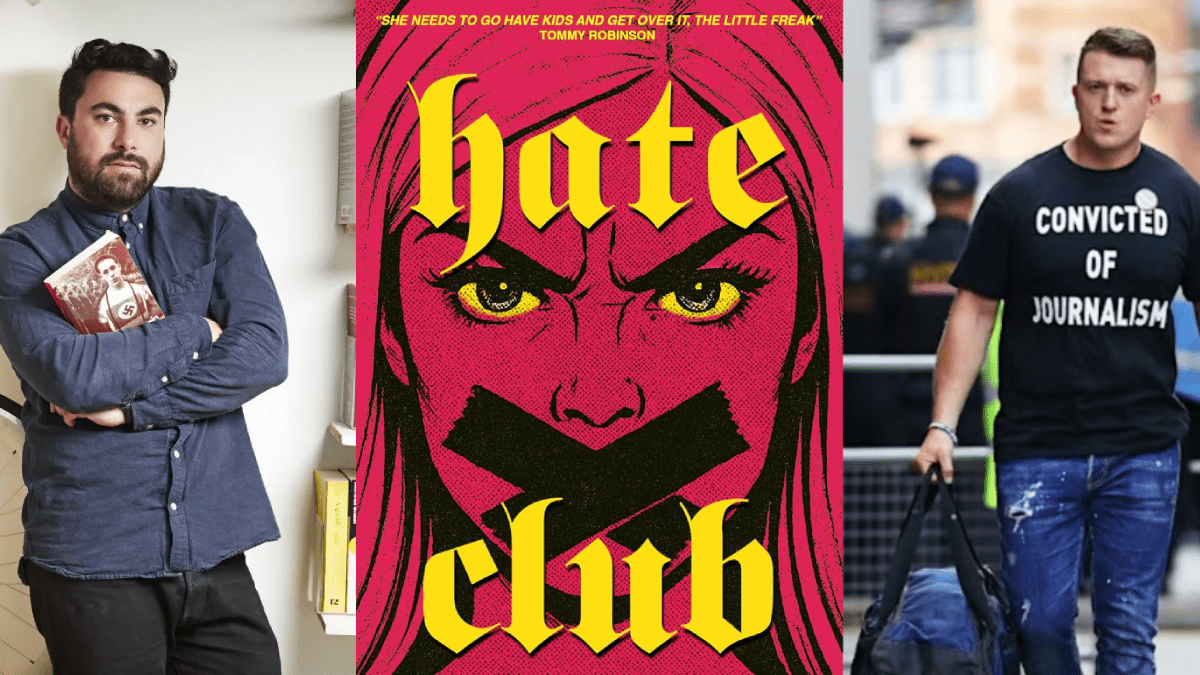

On the day of the Old Bailey trial, I was crouched by the bins, smoking a cigarette. I checked over my shoulder, then hit play. There was Tommy, in a black T-shirt with CONVICTED OF JOURNALISM emblazoned across the chest, gliding through his adoring fans. Flags draped over their shoulders like capes, cardboard signs slapped together with paint, trying to touch his sleeve as if he were some kind of deity.

Gavin McInnes barged alongside in a red tartan suit with a freshly twirled moustache, grinning maniacally. “It’s like Beatlemania!” he shouted to the cameras as the throng lurched left to right.

Then there was Ezra [Levant], wide-eyed, drumming up donations like a carnival barker. “This is it, folks, the fearless warrior for truth! Who’s sacrificed everything for your and our freedom!” Other side of the story, my arse.

I was surprised to see Katie Hopkins there. Last I’d heard, she wanted nothing to do with Tommy, but I suppose once the cameras roll, everyone wants a cameo.

The whole thing was a nauseating spectacle.

I flicked my fag butt and closed the video, my phone buzzing to life with Joe Mulhall’s name flashing across the screen just seconds later. “I guess you’ve seen the news,” he said, his voice dripping with unsettling, assumed familiarity.

“Listen, if you want, we could help you get your story out. Could hit up The Mail or The Guardian, pay you up to five grand. Think about it. We’re working on a Tommy takedown with the BBC over the next few months, if you ever fancy setting him straight, that option’s on the table for you. Alright?”

Click. “Wanker,” I muttered, tossing my phone in the locker, taking my seat next to Bob as the factory hummed back to life.

There was no question, I couldn’t accept money, or work with, or frankly even be polite to, anyone from HOPE not Hate. That money would have saved me, but it was cursed gold.

I was at my local kickboxing class a few weeks later, going through a ritual I’d come to love, wrapping my hands in bandages, pulling on my gloves, stepping forward, left, right, ducking as we waited to begin. The music started, disco lights flashed, and we were off, a mix of local lads and mums, working in pairs, taking turns holding the dummy while the others let rip. “Wow, you’re really improving!” our instructor called over my shoulder as I landed a jumping kick. “You know, I think you’ve finally earned your nickname, Lucy. How about…The Destroyer!”

I smiled, the first real flicker of pride I’d felt in what seemed like a lifetime. I turned to my training partner, flashing a wide grin, but her face was sullen. She adjusted the dummy across her forearm, head bowed, eyes sharp and competitive. I sensed she was annoyed. Feeling like I had to prove I was worthy of the name, I threw everything I had into the next round of kicks as she blocked each one. “Oh! Sorry!” I said, startled, as something hard struck the back of my leg.

I turned instinctively, expecting to see someone behind me, but there was no one. Just empty air, the sound of drum and bass still booming. Then, my leg collapsed.

I dropped, grabbing my foot with both hands. It felt detached, wrong. “Oh no,” said our instructor, crouching beside me. “Let me try something.” He helped me up, telling me to hold the bar and balance on my left leg. “Now try to straighten your right foot.” I couldn’t. It hung limp, stuck in a Barbie point. “Shit,” he muttered. “It’s the Achilles tendon. I think it’s snapped. Oh, today of all days, huh?”

The next morning, I sat in the hospital, a plaster cast drying up to my knee. I’d slept with frozen peas on it, hoping it was something minor. No such luck. “Have you ever injected yourself?” the nurse asked. “You’ll need to do this daily to stop blood clots. If you don’t, one could hit your heart and kill you.” I held the needle over my stomach, hand shaking, bursting into tears. “It’s fine,” she said, “we can give you pills. We’ll see you once every couple of weeks for a sponge bath and bandage change. Bring your own soap. And here are your crutches. Get some foam for the handles. They’ll cut into your palms.” I hobbled out of the revolving doors a few hours later, my naked toes sticking out of the end of the plaster cast, Mum carrying my bag to the car.

I guess I was daft for thinking I deserved even one small win in that wretched year. I was back indoors again, stuck in the boot for at least six months. Talk about solitary confinement.

The two-week ski trip I’d been looking forward to with my parents after Christmas? Forget it. I told them to go without me, insisting I’d be fine. Really, I was terrified. My first thought was: what about when I’m alone at night? The house was old and creaky, the walls dripping with unpleasant memories, and some bastard guest had once told my parents the spare room I was sleeping in was haunted by an old woman.

I tried to think like Bruce Wayne, facing my fears and dealing with it head-on. Besides, the ghost probably felt pity for me anyway, too sad to haunt.

My parents left for two weeks while I hobbled around the house, hovering sideways in the bath to wash, brushing my teeth on the loo. Making a cup of tea was the hardest. You really start to appreciate the human body when a part of yours stops working. It began to feel like some kind of divine penance. After all, I’d once wielded Tommy’s mob against others, like Munroe Bergdorf.

I hadn’t realised until it was too late how much power he held in that phone of his. Maybe this was karma finally catching up with me. My phone lay silent. The TV blared through the night. At least I had Chip, a little piece of life, someone who needed me as much as I needed her.

Caolan [Robertson] rang one morning as I was crawling down the stairs. “Heyyy, how’s your arm?” he said. “You mean leg?” I replied. “Oh yeah, right, leg. Anyway, I was just wondering...we were just wondering...if you could drive George somewhere this afternoon? It’s really urgent, we can pay.” I let out a snort. “Caolan, what part of ‘I’ve broken my leg’ don’t you understand?” He fake-laughed. “Ah, right. Yes. Well...hope you feel better soon.”

Caolan wasn’t the only one asking for favours.

A pair of political lowlifes called, asking for me to chaperone Ashton Birdie, the blonde Infowars starlet, through Cambridge for them to show her around. “So you’re not calling to check how I’m doing?” I said, deadpan. “What? Oh, right. Sorry.”

Just when I thought it couldn’t get any more demeaning, an email popped up in my inbox. “Hi Lucy. Heard about the Tommy drama, awful business. Care to meet up for a coffee? Or something stronger if you like. J.” It was John Sweeney, presenter at the BBC.

“Fuck off,” I said out loud, slamming the screen.

Did I have the word ‘cunt’ written on my forehead? It was as if I had no personality traits beyond being abused anymore.

Muslims used my suffering to promote Islam, antifascists to promote themselves. The journos were the worst of the lot, fawning with offers to buy me lunch like I was some stray in need of a sugar daddy. Nearly every one of them would lean in and admit they “agree with a lot of this stuff, just couldn’t publish it.”

Not a single one seemed to grasp that I was still standing for something, or that I ever had at all. I wasn’t a person to them. I was a line in a column, a payday, a reason to book another weekend away playing golf. My silly little girlish morals were just an obstacle to their good time. Any public concern about mass immigration, rape, grooming, murder or religious extremism had to be written off as misinformation from the right, the rantings of racist gammons led astray by some charismatic hate preacher.

That was the story. It never occurred to them to question it.

I sat there stewing, looking for something to do, and eventually plugged in my old archive. Sipping my coffee, I methodically sifted through the mess of files I’d been saving for months, documenting the far left.

Archiving, like retouching, has a strange, calming rhythm to it, something I’d done in my old job. Throw on some music. Click. Think. Where does this belong? Where does that go? My eyes caught the old McDonald’s footage, the CCTV we’d finally gotten from the police after they dropped the investigation, chuckling as the pixelated version of myself launched a flying kick into the back of an antifascist like a 90s video game.

I began sifting through my HOPE not Hate folder, looking over tweets and snarky blog posts glorifying violence and malicious attacks on their enemies, going as far back as the 60s. I found a statement from Dan Hodges, a former employee, where he wrote:

“We used every dirty, underhand, low-down, unscrupulous trick in the book. Then when the book had been used up, we tore it to shreds, set it on fire, and stuffed it down Nick Griffin’s underpants.”

The very definition of undemocratic.

And yet, in the present day, there they were in the House of Commons, proudly presenting their latest book about the ‘far right,’ tucking into sausage rolls while Labour MPs and celebrities applauded their ‘bravery.’ Who gave them such power? This invisible hand?

Nick Lowles, seated on the Counter Extremism Board, treated as a neutral expert. His colleague Matthew Collins beside him, a “reformed neo-Nazi” who once attacked Muslim women with hammers, now one of their lead writers.

And there they sat, smug and well-fed. Four legs good, two legs bad.

I flicked through their website, reading their report from the Day for Freedom, comparing it to Mosley’s Blackshirts. “Gavin McInnes looking worse for wear at the airport,” one caption read beneath a picture of him waiting in line.

My brain started to churn. How did they know Gavin was at that specific airport, at that specific gate? Wasn’t Caolan in charge of the…flights? No, surely not.

I kept clicking, thinking, reading, remembering. Why had Joe Mulhall come to meet Caolan that night? Why had he let himself get in trouble like that? What was their relationship?

Flippant comments Caolan had made began surfacing: meetings, dinners, drinks. I remembered him telling me he’d met Joe at The Dorchester once, laughing as he said, “It’s funny, going to a fancy restaurant with the enemy. It’s cool, like a spy film, everyone does it.” Do they?

I thought about the times Caolan would use Joe’s name in passing with familiarity, on texting terms. Then there was the day at Speaker’s Corner, when Lutz Bachmann had been barred from entering the UK. Caolan and George had been completely unsurprised and unbothered.

Had they made the call? “Oh my God,” I whispered to myself. It was like that old jigsaw they had on the wall, the missing piece: Caolan. The cars following us. That feeling of being hunted. And those two, always scheming in their own private language, never giving the full story. If I was right, we might as well have invited Joe Mulhall into the sodding car with us, save him the train fare.

I spent the afternoon putting everything I could together in a dossier: pictures, screenshots, dates, half-finished thoughts stacked in bullet points, trying to explain why each strange event made more sense once this new possibility was factored in.

Had Caolan been feeding information to HOPE not Hate all along? That’s what it looked like, I just needed proof.

I worked like it was a final project due the next morning. The more I thought about the boys, the more I felt like some despairing parent, not angry so much as bitterly disappointed. There was an old Cold War stereotype gay men had loose lips when it came to state secrets, something about being too susceptible to pressure, too easily blackmailed, too fond of drama. Caolan liked to feel naughty, decadent, and subversive. Most of all, he loved to bitch. All the traits someone like Joe could exploit, feeding his ego over the table, getting exactly what he wanted, threatening him once the booze wore off.

Finally, around midnight, it was done.

I fired a few copies into the ether like flaming arrows, hoping they’d land in the hands of someone who could blow the lid off the whole thing. I was hauling myself up the stairs one by one backwards, Chip purring at the top, when my phone pinged. I checked it without thinking and nearly slipped.

“Hey, it’s Tommy. Did you get a letter from John Sweeney at the BBC?”

I locked the screen and stared at the banister, pretending I hadn’t seen it. I slid up two more steps on my backside, then stopped and checked again. Still there. You’re lucky I’m injured, I thought, dragging my broken body higher.

The audacity. After everything. No apology, no shame, just raw self-preservation.

Of course he was scared. One interview and his whole rotten empire could fall. The coke. The hookers. The cheating. He must have been sweating, picturing the headlines, me on the telly in tears.

For a moment, I laughed out loud, giddy at the thought of him living even one day in the pit he’d thrown me into. I wanted him ruined. I wanted him crawling. And for once, that power was mine. I could almost see him flinch on the other end of the message, wherever he was. My rage pulsed in the air like static.

Then, as I reached the landing, I remembered something.

“Tommy takedown.” Those were Joe Mulhall’s words. BBC. Tommy takedown. Big one. Was John Sweeney, BBC presenter, part of this little sting? Did they think I’d be more inclined to work with John than HOPE not Hate? Probably. And now I had both of these men, Tommy and Joe, one in each hand, needing something from me. An interesting position for a girl to find herself in.

I had to ask myself, of the two, who really deserved my wrath? The man who set out to destroy me to cover his own sins? Or the man whose job was to destroy my country?

Oh, I hated Tommy, sure, but I’d chosen to work with that bastard. I walked into his murky world with my eyes open, that was on me.

Joe Mulhall? I never gave that prick permission to be in my life. He forced his way in like a smug little creep, hunting us for sport. In any sane world, it would be called stalking. Harassment. Sadism.

But in Joe’s world, we were just outlines on a paper target. He didn’t fight hate. He relished it. Couldn’t bear to be left out of the action, our fun club. The Hate Club. And maybe, just maybe, I had one move left.

My mind began to churn. What if I used Tommy to expose HOPE not Hate? Burn it all down. It wasn’t so mad, after all, I had the element of surprise.

“Yeah…shall we stitch them up?” I texted back before I had a chance to change my mind.