How Long Can The CPS Ignore The Criminality Of Hope Not Hate?

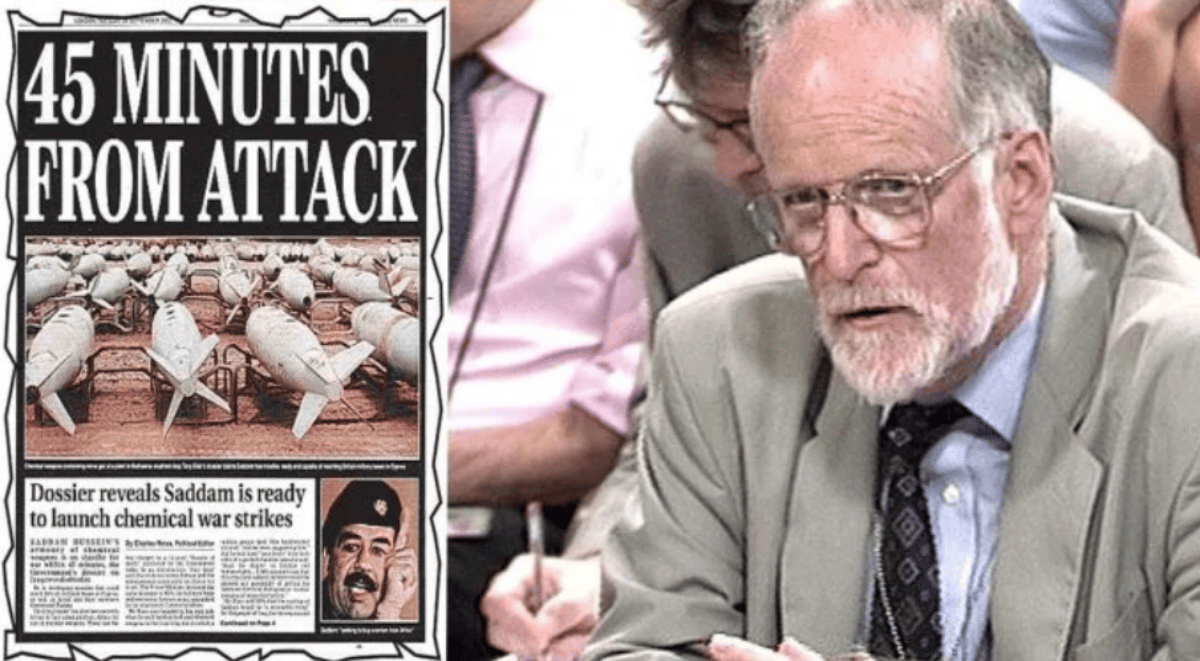

As evidence mounts of ongoing criminal conduct and state involvement, it appears Hope Not Hate is proudly continuing the legacy of its disgraced predecessor, Searchlight. Legal and factual scrutiny of this organisation reveals a cynical exploitation of English law and well-designed tactics.