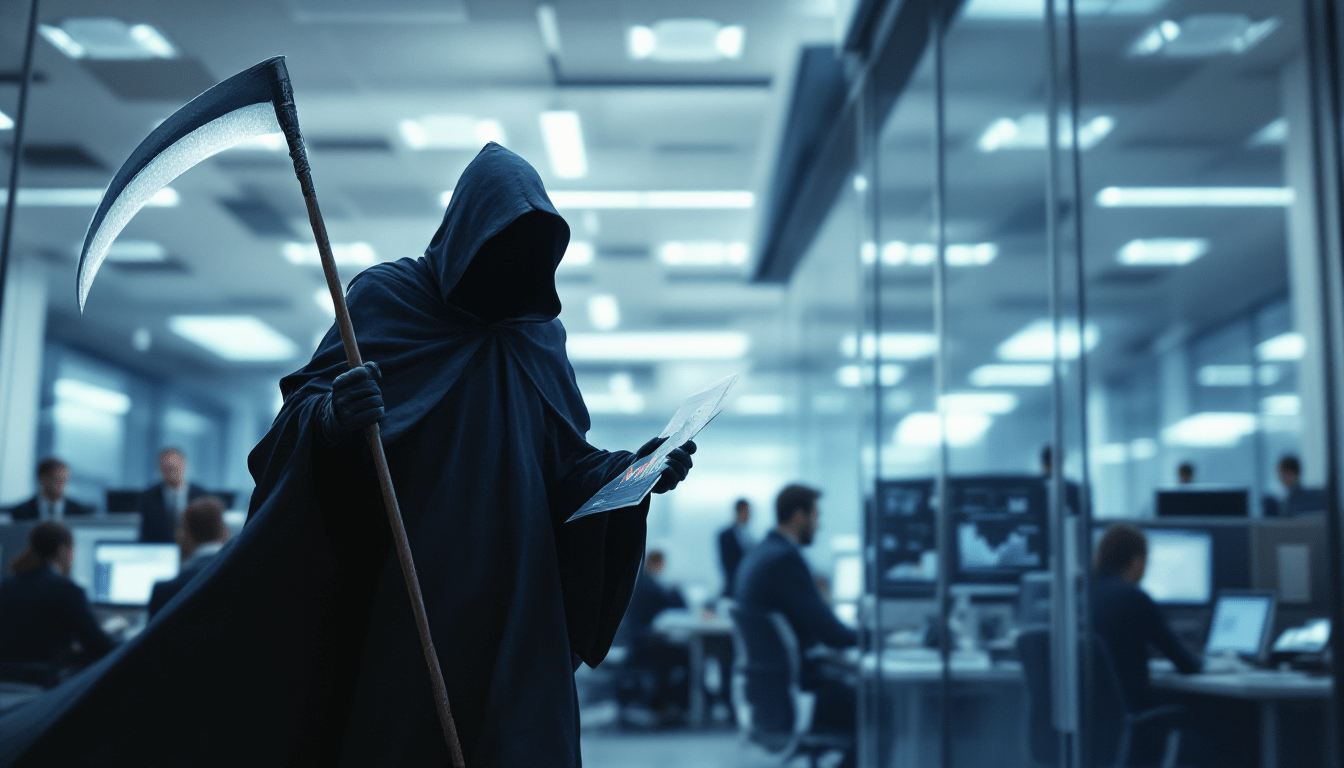

Inverted Yield: The Grim Reaper Of Economics

Since 1970, every major US financial collapse has been foreshadowed by the same warning signal. Finance is dry, boring, and difficult to follow, but when one specific thing goes wrong in the world's backup system, it's like the chest pain before an impending heart attack.