Merchant of Armageddon: Abdul Qadeer Khan's Nuclear Weapons Dealing Network

A metallurgist stole nuclear secrets from Europe, then sold atomic weapons capability like a franchise—complete with manuals, components, and customer support. His clients? Iran, Libya, North Korea. The bombs he helped build are still out there. One man nearly broke the world. A true Bond villain.

1974, the Rajasthan Desert, India. A mushroom cloud rises over Pokhran. Code name: "Smiling Buddha." India has just gatecrashed the nuclear club, and across the border in Pakistan, panic sets in like a fever.

The strategic calculus is brutal and simple. Pakistan's conventional military cannot match India's. The nuclear genie is out of the bottle, and Pakistan needs one of its own—fast. Into this cauldron of existential dread steps Abdul Qadeer Khan, a 38-year-old metallurgist with European credentials, a chip on his shoulder, and access to the crown jewels of Western nuclear technology.

Khan wasn't born into power. Born in 1936 in British India, he studied metallurgy across Europe—Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium—absorbing the cutting edge of materials science during the atomic age's most feverish decades. By the early 1970s, he'd landed a position at URENCO, a Dutch-British-German uranium enrichment consortium. URENCO wasn't just any job. It was the nuclear equivalent of working in Fort Knox whilst holding the keys.

And Khan? He walked out with the blueprints.

The Theft: Stealing the Future

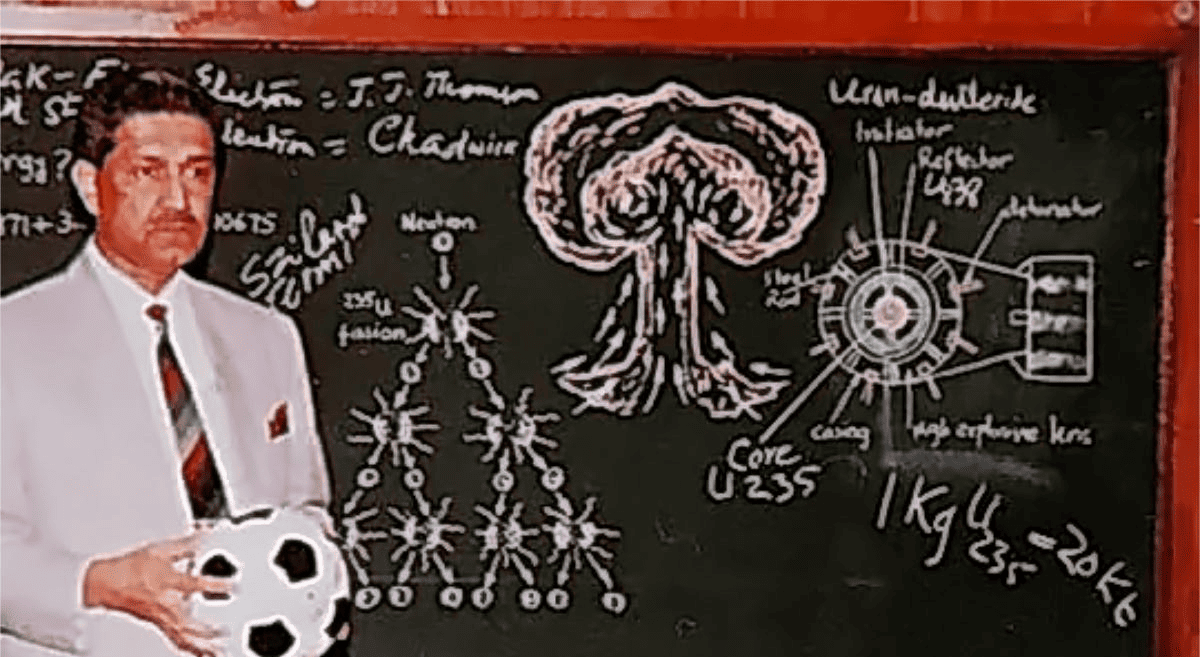

The theft was audacious in its simplicity. Between 1972 and 1975, Khan systematically photographed and photocopied classified centrifuge designs—the spinning cylinders used to enrich uranium from harmless isotopes into weapons-grade fuel. But to understand what Khan stole, you need to understand what a gas centrifuge actually does.

Natural uranium consists primarily of two isotopes: uranium-238 (99.3%) and uranium-235 (0.7%). Only U-235 is fissile—capable of sustaining a nuclear chain reaction. To build a bomb, you need to increase the concentration of U-235 from 0.7% to roughly 90% or higher. This is enrichment.

Gas centrifuges accomplish this through physics so elegant it borders on beautiful. Uranium hexafluoride gas (UF6) is fed into a rapidly spinning cylinder—and when we say rapidly, we mean 50,000 to 70,000 revolutions per minute, faster than a jet engine. At these speeds, the heavier U-238 molecules experience slightly more centrifugal force than the lighter U-235 molecules, causing them to concentrate near the cylinder's outer wall whilst U-235 accumulates closer to the centre.

The difference is minuscule—we're talking about a mass difference of just three neutrons—but cascade enough centrifuges together, each one marginally enriching the uranium before passing it to the next, and eventually you can produce weapons-grade material.

The centrifuges Khan stole designs for were technological marvels. Each rotor had to be machined from maraging steel—a nickel-cobalt alloy capable of withstanding enormous rotational stresses without fracturing. The tolerances were absurdly tight, measured in microns. The slightest imbalance at 50,000 RPM would cause catastrophic failure. You needed vacuum pumps capable of maintaining near-perfect vacuums inside each centrifuge. You needed frequency converters to control the precise electrical current driving the motors. You needed molecular pumps, magnetic bearings, specialised gaskets resistant to the viciously corrosive uranium hexafluoride.

Khan didn't stop at the technical drawings. He copied supplier lists, procurement routes, specifications for every obscure component. The names of companies in Germany manufacturing maraging steel. Swiss firms producing vacuum equipment. British manufacturers of frequency converters. Everything you'd need to bootstrap a nuclear weapons programme from scratch.

Then he simply… left. Returned to Pakistan with a suitcase full of secrets and a nation desperate enough to lionise him.

Building the Bomb

Within a decade, Pakistan had the bomb. The programme Khan oversaw at Kahuta, outside Islamabad, built Pakistan's first cascade of gas centrifuges. By the mid-1980s, Pakistan could enrich uranium. By 1998, they'd conducted underground nuclear tests at Chagai Hills in Balochistan—six devices detonated over two days, announcing Pakistan's arrival as the world's seventh declared nuclear power.

Khan became a national hero, fêted as the "father of the Islamic bomb," his face on postage stamps, his name whispered with reverence. The man had delivered what politicians and generals only dreamed of—strategic parity with India, insurance against annihilation, a seat at the table reserved for nuclear powers.

But for Khan, being a national hero wasn't enough.

He'd tasted something intoxicating during those years of espionage and engineering—power. The power to reshape history. The power to sell it. And so, sometime in the late 1980s, A.Q. Khan went rogue. Or perhaps he'd always been rogue. Either way, he transformed from Pakistan's saviour into the world's most dangerous merchant.

The Franchise: Selling Armageddon

Khan didn't just sell nuclear materials. He sold capability. He built what intelligence analysts would later describe, with barely concealed horror, as a "franchise model" for atomic weapons. Think of it as McDonald's, but for mushroom clouds.

His network operated through a bewildering constellation of shell companies, middlemen, and commercial fronts scattered across three continents. Need centrifuges? Khan's network could source them through companies in Malaysia and Dubai. Need vacuum pumps? Try suppliers in Switzerland and Turkey. Maraging steel? South Africa had some excellent deals.

The beauty—if one can use such a word—was in the obfuscation. Each component was ostensibly "dual-use," meaning it had legitimate civilian applications. A vacuum pump is just a vacuum pump. Frequency converters run industrial equipment. Maraging steel makes golf clubs and aircraft landing gear. Individually, none screamed "nuclear weapons programme."

But assembled? You had everything necessary to enrich uranium to weapons-grade purity.

Khan's network supplied complete centrifuge packages. The P-1 design he proliferated was based on the CNOR (Centec Nederlands Oorsprong) design from URENCO—an aluminium-rotor machine capable of 3 to 5 Separative Work Units (SWU) per year. One SWU represents the effort required to separate a certain amount of uranium into enriched and depleted streams. To produce 25 kilograms of weapons-grade uranium—enough for one bomb—you need roughly 5,000 SWU. Cascade 1,000 P-1 centrifuges together, run them for a year, and you've got a bomb's worth of material.

The P-2 design was even better—a maraging steel rotor with roughly double the P-1's output. Faster, more efficient, harder to build but devastatingly effective once operational.

Khan sold complete packages: centrifuge designs, assembly manuals, procurement lists, even warhead schematics. He offered consultancy, after-sales support, troubleshooting. One intelligence official later remarked it was like buying an IKEA flat-pack, except the instruction manual was for building civilisation-ending devices.

The clientele? A rogues' gallery of pariah states and budding nuclear aspirants.

Iran: The Foundation

Iran was arguably Khan's first major client, receiving both P-1 and P-2 centrifuge designs in the mid-1980s. The transaction happened through intermediaries—meetings in Dubai hotel rooms, briefcases exchanged, technical documents changing hands. These weren't theoretical blueprints. They were working models, tested and refined through Pakistan's own programme.

Tehran used Khan's designs as the cornerstone of an enrichment programme now decades old and counting. The Natanz Fuel Enrichment Plant, buried partially underground in the desert south of Tehran, houses thousands of centrifuges—cascades organised in halls the size of aircraft hangars. When International Atomic Energy Agency inspectors first entered Natanz in 2003, they found IR-1 centrifuges—Iran's designation for machines based directly on Khan's P-1 design.

Every time Western diplomats sit across from Iranian negotiators arguing about uranium stockpiles and breakout timelines, Khan's ghost hovers over the table. The centrifuges spinning in Natanz and Fordow? Direct descendants of the technology Khan stole from URENCO thirty years earlier, packaged and sold like industrial equipment.

Iran has since developed more advanced designs—the IR-2m, IR-4, IR-6—but the technological foundation remains Khan's stolen blueprints. The country now has the capacity to enrich uranium to 60% U-235 concentration, just below weapons-grade. The breakout time—how long it would take Iran to produce enough highly enriched uranium for a bomb if they chose to—is now measured in weeks, not years.

Libya: The Complete Package

Muammar Gaddafi wanted the bomb, and Khan was happy to oblige. The Libyan deal was comprehensive—complete centrifuge sets, warhead design information, operational guidance. Libya was getting the full package, a nuclear weapons capability delivered like a mail-order service.

The centrifuges shipped to Libya included both P-1 and P-2 models, some fully assembled, others in components. But Khan went further. His network provided Libya with actual warhead designs—blueprints for a Chinese-origin nuclear device, compact enough to fit atop a ballistic missile. The design showed a two-point implosion system, where conventional explosives compress a subcritical sphere of highly enriched uranium into a supercritical mass, triggering a nuclear explosion.

Had Gaddafi not suffered a crisis of confidence (or calculation) in 2003 and abandoned his programme, Libya might have joined the nuclear club within a decade. Instead, Tripoli's warehouses became crime scenes, packed with evidence of Khan's dealings. When American and British intelligence officers entered those facilities, they found gas centrifuges still in their crates, technical drawings showing cascade configurations, and—most alarmingly—warhead designs showing precisely how to machine uranium into bomb cores.

North Korea: The Devil's Bargain

Pyongyang already had a plutonium programme, centred on the Yongbyon Nuclear Scientific Research Centre. Plutonium is the other route to nuclear weapons—instead of enriching uranium, you irradiate uranium-238 in a nuclear reactor, transmuting it into plutonium-239, then chemically separate the plutonium from the spent fuel. North Korea had mastered this by the early 1990s.

But centrifuges offered a parallel path using highly enriched uranium. Khan provided centrifuge technology; in exchange, North Korea offered missile designs. It was a barter system for the apocalypse. You give me the means to deliver nuclear weapons across continents, I'll give you the means to build them in the first place.

The evidence for this exchange came from multiple intelligence sources. Pakistani transport aircraft were spotted at Pyongyang's airport. North Korean officials visited Khan's facilities in Pakistan. Components matching those used in North Korean missiles turned up in Pakistani inventories.

Today, North Korea's nuclear arsenal—now potentially dozens of warheads strong—rests partly on foundations Khan laid. Every missile test Pyongyang conducts, every threat Kim Jong Un issues, carries Khan's fingerprints. The centrifuges operating in hidden mountain facilities? Traceable back to designs Khan proliferated two decades ago.

North Korea's Kangsong Electric Trading Company—the front organisation managing their centrifuge programme—acquired aluminium tubes with the precise specifications needed for P-1 centrifuges. Investigators found procurement records showing North Korean agents purchasing maraging steel, vacuum pumps, and frequency converters from the same suppliers Khan's network used.

Satellite imagery of North Korean facilities shows buildings with the distinctive layout of centrifuge halls—long, narrow structures with heavily reinforced roofs, often built partially underground to resist aerial attack. The configurations match known cascade arrangements for P-1 and P-2 centrifuges.

Intelligence agencies suspect Khan's network touched other states—Syria, Saudi Arabia, possibly more. The full client list remains classified, a roster of shame locked in vaults in Langley, Vauxhall Cross, and Islamabad.

The Unravelling

Every thriller needs a twist, and Khan's came in 2003 when Muammar Gaddafi—spooked by the Iraq invasion and seeking rehabilitation—decided to come clean.

Libya invited Western inspectors in, opening the doors to warehouses stacked with centrifuges and warhead designs. Intelligence agencies traced serial numbers, shipping manifests, financial transactions. All roads led back to Khan.

The breakthrough came with a shipment aboard the BBC China, a German-owned vessel intercepted in October 2003. Inside: centrifuge components bound for Libya, routed through Dubai, ordered through Khan's network. The cargo included precision-machined aluminium tubes, each 1.3 metres long and manufactured to tolerances of 0.1 millimetres—exactly the specifications for P-1 centrifuge rotors. There were molecular pumps, bellows assemblies, electrical components. Every piece meticulously catalogued, every serial number traced.

The intercepted cargo was a Rosetta Stone, unlocking years of covert transactions and revealing the staggering scope of Khan's operation. Intelligence services traced the aluminium tubes to a manufacturer in Malaysia operating under the name SCOPE. They tracked vacuum pumps to a Turkish supplier. Frequency converters had originated in Switzerland, then been reshipped through Dubai free-trade zones where customs inspections were perfunctory at best.

Pakistan, now facing international pressure and acute embarrassment, forced Khan onto national television in February 2004. He read a prepared confession, taking full responsibility, absolving Pakistan's government and military of any knowledge or complicity.

It was theatre, obviously—nobody seriously believed Khan operated a global nuclear smuggling ring without state protection—but it gave Islamabad plausible deniability. Khan was placed under house arrest. No international prosecution. No extradition. Pakistan shielded him, protecting both a national icon and, presumably, secrets too sensitive to air in open court.

The Enduring Legacy

Khan died in 2021, aged 85, still revered by many Pakistanis as a patriot and pillar of national security. His funeral drew thousands. Politicians praised his contributions. To them, he was the man who'd secured Pakistan's survival.

To the rest of the world? He was the man who proved nuclear proliferation could be industrialised, commercialised, and globalised using nothing more than shell companies, corrupt suppliers, and a Rolodex of willing clients.

The consequences of Khan's network endure, reverberating through every major nuclear crisis of the 21st century.

Iran's enrichment programme remains a geopolitical flashpoint, its origins traceable directly to Khan's blueprints. Every round of negotiations over Tehran's nuclear ambitions is haunted by the centrifuges he sold three decades ago. The programme has survived sanctions, sabotage, assassinations, and diplomatic isolation—in no small part because Khan gave Iran a technological foundation robust enough to weather them all.

The Natanz facility now houses over 5,000 operational centrifuges, with thousands more in storage. Iran's stockpile of enriched uranium exceeds 4,000 kilograms at various enrichment levels—far beyond what any civilian nuclear programme requires. The country has mastered the full fuel cycle, from uranium mining through conversion to UF6 gas, enrichment, and reconversion into reactor fuel or (potentially) bomb material.

North Korea's arsenal continues expanding, with centrifuge designs bearing unmistakable hallmarks of Khan's stolen URENCO technology. Pyongyang's ability to enrich uranium gives it a second pathway to the bomb, complicating containment efforts immeasurably. The United States can destroy plutonium reactors from the air; centrifuge facilities can be hidden in mountains, dispersed across a country, concealed in ways satellites struggle to detect.

The Punggye-ri Nuclear Test Site, where North Korea conducted six nuclear tests between 2006 and 2017, showed yields progressing from less than one kiloton to possibly 250 kilotons—roughly fifteen times the Hiroshima bomb. Some of those devices almost certainly used highly enriched uranium produced in centrifuges descended from Khan's designs.

Nuclear latency now exists in roughly a dozen countries—states with the technical knowledge, industrial base, and (in some cases) undeclared stockpiles of components necessary to assemble a weapon within months if political circumstances shift. Khan's network seeded capabilities worldwide, creating a proliferation risk the international community still struggles to contain.

The New Nuclear Reality

The Khan network shattered assumptions about nuclear security. For decades, policymakers believed nuclear weapons technology could be ring-fenced—controlled through export regimes, intelligence monitoring, and diplomatic pressure. Khan proved otherwise. He demonstrated nuclear capability could spread horizontally across adversarial states using commercial supply chains, covert logistics, and middlemen insulated from state oversight.

Before Khan, proliferation was vertical—superpowers helping client states in exchange for geopolitical loyalty. The Soviet Union assisted China. The United States shared technology with Britain. France helped Israel. After Khan, it became horizontal—rogues helping rogues, bypassing traditional power structures entirely.

The technical barriers to nuclear weapons haven't disappeared, but they've lowered dramatically. The physics hasn't changed—you still need to enrich uranium or produce plutonium, still need to solve the engineering challenges of implosion systems and neutron initiators. But the knowledge is out there now, proliferated through Khan's network and impossible to recall.

A country starting a clandestine nuclear programme today doesn't need to reinvent the centrifuge. They can use Khan's stolen P-1 design as a blueprint, source components from the same suppliers his network used, follow procurement routes already established. The infrastructure for nuclear proliferation exists as a kind of shadow economy, dormant but ready to be activated.

The Unanswered Question

Why did he do it?

The question lingers, unanswered and perhaps unanswerable. Was it ideology—a pan-Islamic vision of nuclear parity, empowering Muslim-majority states against perceived Western and Indian dominance? Khan occasionally hinted at such motivations, framing his work as levelling a rigged playing field. He spoke of humiliation, of the West's double standards, of a world where some nations could possess apocalyptic weapons whilst others were denied even the knowledge.

Was it greed? Khan amassed considerable wealth. His network generated millions. Mansions, luxury goods, offshore accounts—the trappings of a man who'd monetised Armageddon. Investigators found evidence of payments flowing through banks in Dubai, Switzerland, Malaysia. Khan lived well. Very well. His properties in Islamabad were palatial. He drove luxury cars, travelled first-class, maintained accounts across multiple jurisdictions.

Or was it ego? The intoxication of wielding world-historical power, of knowing presidents and prime ministers courted your favour, of being indispensable? Khan relished his role. He gave interviews (carefully sanitised), cultivated his legend, basked in adulation. In Pakistan, schoolchildren learned his name alongside the founders of the nation. Abroad, intelligence agencies obsessed over his movements.

Probably all three. Human motivation rarely reduces to single variables, especially in men who fancy themselves architects of destiny.

What remains indisputable: A.Q. Khan built the first private nuclear proliferation enterprise. He constructed a network spanning continents, clients, and decades. He transformed nuclear weapons from state secrets into commercial assets available for purchase.

The world order had always assumed nuclear weapons would remain the exclusive province of stable, established powers—states with bureaucracies, oversight mechanisms, deterrence doctrines. Khan upended this. He proved a single determined individual with the right access and lack of scruples could proliferate weapons of mass destruction as casually as selling cars.

The Pause

There's a moment in the 2004 confession where Khan, reading from his script on Pakistani television, pauses. Just for a second. His eyes flicker. Then he continues, accepting sole responsibility, exonerating everyone else.

What was going through his mind in those seconds? Regret? Defiance? Fear? We'll never know.

But here's what we do know: the bombs Khan helped create are still out there, sitting in silos and bunkers and mountain facilities, ready to obliterate cities at a moment's notice. The knowledge he spread cannot be unspread. The capabilities he sold cannot be unbought.

Iran will not forget how to build centrifuges. The IR-1 design is now indigenous Iranian technology, manufactured in facilities across the country. They've moved beyond Khan's blueprints, developing advanced models with carbon-fibre rotors achieving higher RPMs and greater efficiency. The technical foundation remains, but the capability has matured into something self-sustaining.

North Korea will not abandon its uranium enrichment programme. The country has invested decades and scarce resources into mastering the technology. Satellite imagery suggests at least one major centrifuge facility at Yongbyon, possibly others at undeclared sites. The programme provides strategic insurance—a second pathway to nuclear weapons independent of the plutonium reactors.

The dozen or so countries with nuclear latency will not voluntarily surrender the technical expertise Khan's network provided. That knowledge resides in the minds of scientists and engineers, in technical libraries, in industrial capabilities. It cannot be uninvented.

The genie doesn't go back in the bottle.

Patriot or Traitor?

Khan's defenders in Pakistan argue he was a patriot, doing what was necessary for national survival. His detractors call him a traitor to humanity, a man who brought the world closer to nuclear catastrophe than anyone since the Cold War's darkest days.

Both might be right.

What's certain is this: A.Q. Khan demonstrated something terrifying. He proved the most dangerous technologies could be commodified, franchised, sold to the highest bidder. He showed the world doesn't need supervillains with grand ideological visions or nation-states with vast resources to spread weapons of mass destruction.

Sometimes all you need is one man with a briefcase, a network of suppliers, and absolutely no regard for consequences.

The world survived A.Q. Khan.

Whether it survives his legacy remains an open question.