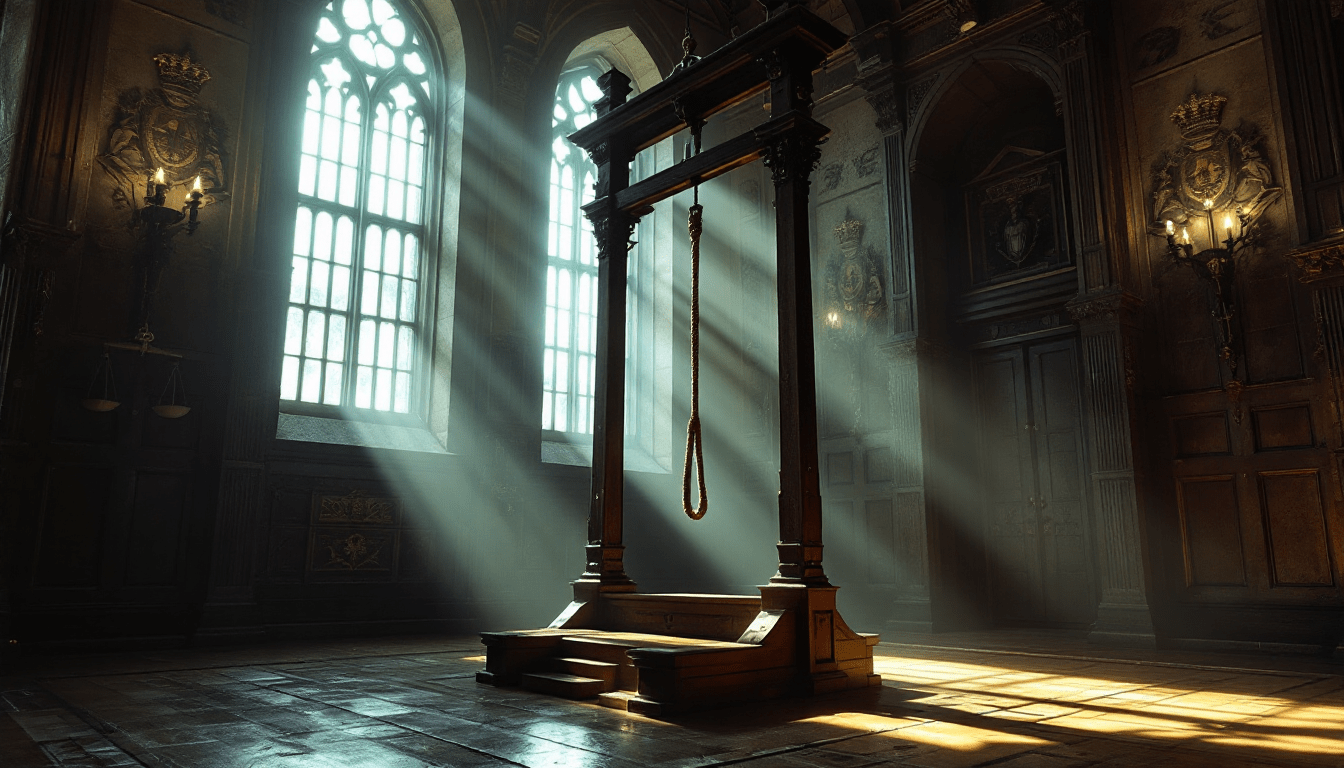

Reinstating The Ancient English Answer To Evil

The rope represents England's final argument against barbarism. DNA evidence now eliminates wrongful executions whilst criminals film their own crimes. Britons have always agreed some evil cannot be rehabilitated—only eliminated. English wrath demands proportionate punishment: life for life.