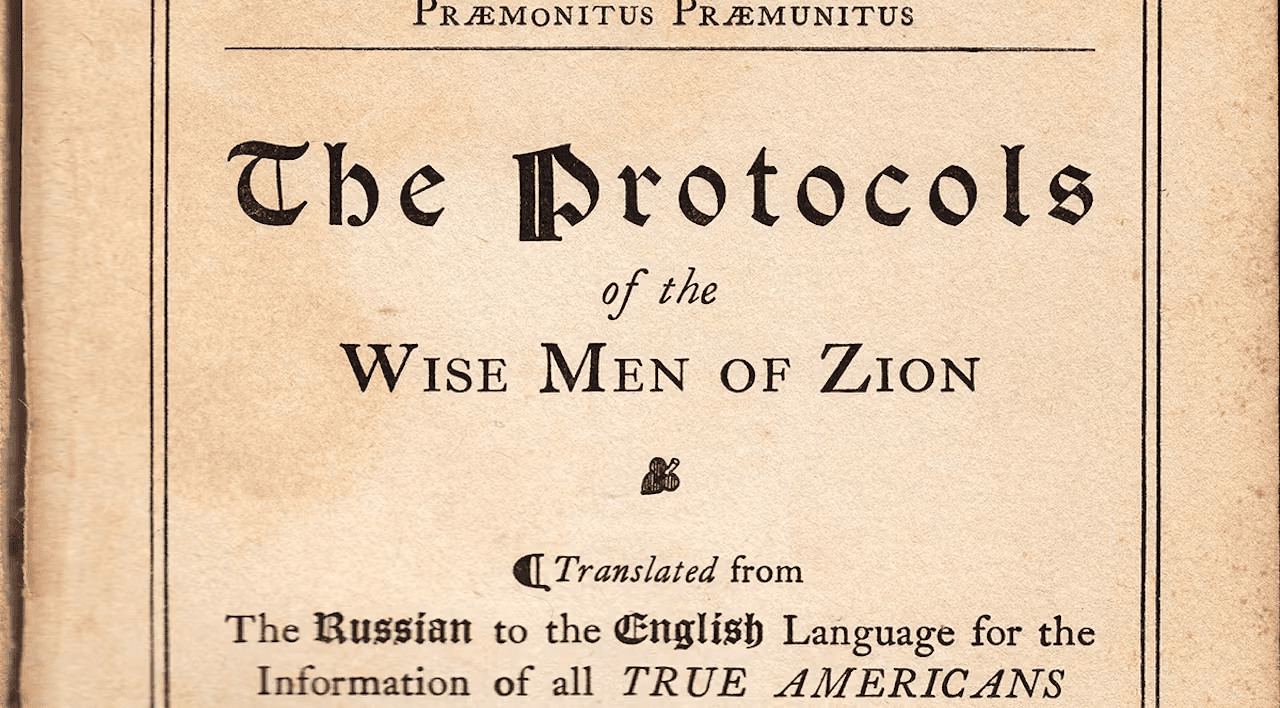

Revisiting The Fraudulent Protocols Of The Elders Of Zion

Britain has defeated antisemitism over and over again. Our most modern wasn't walking into the camps, it was The Times proving the most notorious blood document in history was fraud. This powerful story continues to drive notorious theories now, including the idea elite groups sacrifice children.

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion stands as perhaps the most consequential literary fraud in modern history. This fabricated document, purporting to reveal a Jewish conspiracy for global domination, has fuelled violence for over a century, from the pogroms of Tsarist Russia to the rhetoric of Nazi Germany and beyond. Yet despite being conclusively exposed as a forgery nearly a century ago, it continues to circulate, mutate, and poison minds across the globe.

The Fever Dream of Late Imperial Russia

The turn of the 20th century found the Romanov dynasty in profound crisis. The 1905 Revolution had shaken the autocracy to its foundations. Workers' soviets had sprung up in major cities. Mutinies had erupted in the armed forces, most famously aboard the battleship Potemkin. Tsar Nicholas II, weak and indecisive, had been forced to concede a constitution and a parliament, the Duma, though he would spend the following years systematically undermining both.

The Russian establishment needed scapegoats, and they needed them desperately. The empire's Jewish population—restricted to the Pale of Settlement, subject to discriminatory laws, barred from most professions and universities, and periodically targeted by state-sanctioned pogroms—provided a convenient target. When revolutionary movements gained strength, the fact some revolutionaries were Jewish (hardly surprising given the circumstances) allowed reactionaries to conflate Judaism itself with political subversion. Never mind the thousands of Jewish shopkeepers, artisans, and labourers who had no involvement whatsoever in revolutionary politics. Never mind the ethnic Russian revolutionaries who formed the bulk of these movements.

Into this toxic soil, the Protocols would be planted, where it would flourish like a noxious weed.

The Genesis of a Forgery

The document appears to have been fabricated sometime between 1897 and 1903, most likely in Paris. The principal architect was probably Matvei Golovinski, a Russian émigré, journalist, and Okhrana agent. The Okhrana—the Tsarist secret police—maintained an extensive foreign operations division, particularly concerned with Russian revolutionary émigrés living abroad. Golovinski worked under Pyotr Rachkovsky, head of the Okhrana's Paris office, who had a particular interest in producing propaganda to discredit the regime's enemies, real and imagined.

Rachkovsky was no crude policeman. He was sophisticated, cultured, and understood the power of ideas. He recognised propaganda need not be true to be effective. In fact, the more outrageous the claim, the more it might stick in the public imagination. If you could convince people their enemies were engaged in a vast conspiracy, you could justify almost any repressive measure as necessary self-defence.

The Protocols first appeared in print in Russia in 1903, serialised in the newspaper Znamya (The Banner), a publication of the antisemitic Black Hundreds movement. However, the document gained wider circulation through the 1905 edition published by Sergei Nilus, a Russian mystic and religious writer who included it in his book The Great within the Small and Antichrist, an apocalyptic work mixing Orthodox mysticism with political paranoia. Nilus presented the document as the minutes from secret meetings of Jewish leaders—the so-called "Elders of Zion"—plotting world domination through control of finance, media, and revolutionary movements.

The timing was deliberate.

The 1905 Revolution had terrified the Russian establishment. By publishing the Protocols in this context, Nilus and his allies could suggest the revolution was not a response to genuine grievances but rather the orchestrated work of a Jewish conspiracy. It transformed a political crisis into a racial threat, poverty and oppression into puppet strings pulled by sinister masterminds.

Maurice Joly and Shameless Plagiarism

The most damning evidence against the Protocols comes from a simple comparison with an earlier satirical work, a discovery made by an Englishman thousands of miles from Russia. In August 1921, Philip Graves, Constantinople correspondent for The Times, published a series of three articles demonstrating the Protocols had been plagiarised—in some cases almost word for word—from a completely unrelated French satire written nearly sixty years earlier.

The source was Dialogue in Hell Between Machiavelli and Montesquieu (Dialogue aux enfers entre Machiavel et Montesquieu), written by Maurice Joly in 1864. Joly was a French lawyer and satirist who opposed Napoleon III's authoritarian Second Empire.

His book was a thinly veiled attack on the emperor's despotic methods, featuring the ghost of Machiavelli outlining cynical strategies for maintaining autocratic power in debate with the ghost of Montesquieu, who represented liberal and constitutional principles. The work contained no mention of Jews whatsoever. It was purely political satire about French politics, and a rather transparent one at that. The authorities were not amused. Joly was prosecuted, imprisoned for fifteen months, and his book was suppressed.

The forgers of the Protocols simply lifted Joly's text, made modifications, and reframed Machiavelli's speeches as the supposed plans of Jewish conspirators. They were so brazen in their theft, so confident their forgery would never be traced back to an obscure French political pamphlet from decades earlier, they barely bothered to disguise the plagiarism.

How did Graves make this extraordinary discovery?

He was approached by a mysterious Englishman (possibly a White Russian émigré) who provided him with a copy of Joly's book, explaining the connection. Graves immediately recognised the significance. Working methodically through both texts, he documented passage after passage of near-identical material.

Joly's Dialogue has Machiavelli say:

Like the god Vishnu, my press will have a hundred arms, and these arms will give their hands to all the different shades of opinion throughout the country.

The Protocols states:

These newspapers, like the Indian god Vishnu, will be possessed of hundreds of hands, each of which will be feeling the pulse of varying public opinion.

The similarity is not coincidental or parallel thinking. It is verbatim copying with minor alterations for context. The obscure reference to Vishnu (the Hindu deity) appearing in both a French satire about Napoleon III and a supposed Jewish conspiracy document purporting to be ancient wisdom should alone raise profound suspicions. What would ancient Jewish leaders know or care about Hindu deities?

Scholars subsequently identified approximately 160 passages in the Protocols showing clear derivation from Joly's work. Some sections were copied nearly word for word. Others were lightly paraphrased. The structural arguments, the sequence of topics, even the rhetorical flourishes, all lifted from Joly.

Here is another telling comparison. Joly wrote:

Our government will hold in its hands a great force which will enable it to subject to its will the thoughts and actions of the masses.

The Protocols echoes:

In our hands is a great contemporary power—gold. In two days we can obtain from our storehouses any quantity we may please.

The structure remains identical. The syntax parallels closely. Only specific details have been changed to suit the antisemitic agenda, replacing "government" with explicitly Jewish references and "great force" with the antisemitic stereotype of Jewish financial power.

Graves published his findings in The Times, one of the world's most respected newspapers, under the headline "The Truth About the Protocols: A Literary Forgery." His articles created a sensation. Here was conclusive proof the document was fraudulent. The forgers had been caught red-handed, their plagiarism exposed line by line.

One might imagine this would be the end of the matter. A respected British newspaper, with Britain's considerable international prestige behind it, had definitively proven the Protocols was a fake. Surely this would kill the document's credibility.

One would be wrong.

The Goedsche Connection and Other Sources

Another significant source for the Protocols was a novel by German writer Hermann Goedsche, writing under the pseudonym Sir John Retcliffe. His 1868 novel Biarritz contained a chapter titled "In the Jewish Cemetery in Prague," depicting a secret midnight meeting of representatives from the twelve tribes of Israel, plotting to control the world through gold, the press, and revolutionary movements.

Goedsche's chapter was pure Gothic fiction, complete with atmospheric cemetery settings and theatrical dialogue. Yet this fictional chapter began circulating separately from the novel, presented as though it were factual reportage of an actual meeting.

The antisemitic press stripped away the novelistic framing and published it as "The Rabbi's Speech," claiming it was authentic documentation of Jewish conspiracy. Goedsche himself apparently made no effort to correct this misrepresentation, perhaps flattered by the attention or sharing the antisemitic sentiments his fiction was being used to promote.

The forgers of the Protocols drew upon Goedsche's fiction, Joly's satire, and various other sources from antisemitic literature, creating a hybrid forgery that combined elements from multiple texts.

They were synthesising existing antisemitic tropes and plagiarised material into a single document designed to appear ancient and authoritative.

It was not created from whole cloth by a single fevered imagination. Rather, it was assembled from pre-existing materials, reflecting common antisemitic beliefs already circulating in European culture. The forgers were not inventing new slanders. They were codifying and systematising existing prejudices, giving them the veneer of documentary evidence.

When the Lie Reveals Itself

The text references events, technologies, and political situations from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, yet purports to be ancient wisdom passed down through generations of Jewish elders. It discusses modern railways, mass circulation newspapers, constitutions, parliamentary democracy, and liberal political philosophy—concepts entirely foreign to any supposed ancient conspiracy.

The Protocols speak constantly of manipulating "the press" and controlling "public opinion" through mass media, distinctly modern concerns. An actual ancient Jewish conspiracy, if such an absurd thing could exist, would have no framework for discussing the power of newspapers or the manipulation of parliamentary democracies. These are concerns of the modern age, revealing the document's true origins in turn-of-the-century politics.

The supposed conspirators claim simultaneous control over both capitalism and revolutionary communism—mutually contradictory economic systems locked in existential struggle. This reveals the text's true purpose: not to present a coherent conspiracy theory, but to provide a framework for blaming Jews for whatever the reader already fears or dislikes. Worried about capitalism and exploitation? The Jews control international finance. Frightened of revolutionary communism? The Jews are behind Bolshevism. The Protocols functions as an all-purpose scapegoating device, infinitely flexible because it makes no genuine attempt at logical consistency.

The supposed conspirators openly discuss their own evil intentions in dramatic, villain-like terms. They practically cackle with malevolence. Real conspirators, engaged in actual criminal or immoral activities, do not convene meetings where they explicitly label themselves as evil and discuss their malevolent plots in such melodramatic terms. They rationalise their actions as necessary, justified, or even righteous.

The language of the Protocols resembles cheap melodrama, the moustache-twirling villain revealing his dastardly plans to the captive hero. It reads like propaganda because it is propaganda.

The document is titled "protocols," suggesting meeting minutes or procedural records. Yet the text reads like manifestos or speeches, long monologues outlining plans and philosophies. Real meeting protocols contain discussions between multiple parties, disagreements, votes, procedural matters, mundane logistics.

The Protocols contain none of this institutional texture. They read as uninterrupted declarations of intent, which no actual meeting minutes would ever resemble. The forgers chose the word "protocols" to suggest authenticity and officialdom but could not be bothered to actually mimic the form of genuine institutional records.

The British Discovery

The exposure of the Protocols by The Times of London in 1921 represented a crucial moment, demonstrating the importance of journalistic integrity and the power of careful investigation. Britain, at this point in history, stood at the height of its imperial power and cultural influence. The Times was not merely a newspaper but an institution, often called "The Thunderer" for its authoritative pronouncements on public affairs. When The Times spoke, the world listened.

Philip Graves was an experienced foreign correspondent, the grandson of the Irish poet Alfred Perceval Graves and member of a distinguished literary family. He had covered the First World War and its aftermath, witnessing firsthand the chaos of collapsing empires and the rise of new ideologies. He understood the dangerous power of propaganda, having watched its effectiveness during the war.

The Times published Graves's findings prominently across three days in August 1921. The articles were meticulous, scholarly, and devastating. Graves laid out the evidence methodically, quoting extensively from both Joly and the Protocols to demonstrate the plagiarism beyond any reasonable doubt. He contextualised the forgery within Russian politics and the Okhrana's history of dirty tricks. He appealed to reason and evidence, confident British readers would reject such obvious fraud once the truth was revealed.

The British establishment's reaction was swift. Lord Northcliffe, the newspaper magnate who had championed the Protocols in some of his publications, immediately reversed course. The Morning Post, which had serialised the Protocols in 1920, fell silent on the subject. Winston Churchill, who had previously given some credence to fears of Jewish Bolshevism, distanced himself from the document.

The British exposure was particularly significant because Britain itself had a complicated relationship with antisemitism and with Jews more broadly. Medieval England had expelled its Jewish population in 1290 under Edward I, one of the earliest such expulsions in European history. Jews were only officially readmitted under Oliver Cromwell in the 1650s. Even in the modern era, casual antisemitism remained common in British society, particularly in certain aristocratic and intellectual circles.

The British self-conception emphasised rationality and justice, however imperfectly realised in practice. When confronted with clear evidence of a malicious forgery, significant portions of the British establishment chose to reject it, prioritising evidence over prejudice. This was far from universal; antisemitism certainly persisted in Britain. But The Times's exposure did limit the Protocols' circulation in British intellectual and political life.

Moreover, Britain's global influence meant The Times's debunking reached far beyond British shores. The newspaper was read in every corner of the British Empire and throughout Europe and America. Graves's articles were translated and republished internationally. For anyone willing to look, the evidence was now readily available.

The Berne Trials

The most authoritative legal dismantling of the Protocols occurred in Switzerland in the 1930s, in what became known as the Berne Trials. These proceedings represent the most thorough judicial examination of the document's authenticity ever conducted, a moment where law, scholarship, and human decency converged to definitively declare the truth.

The trials arose from the activities of the Swiss National Front, which in the early 1930s was actively distributing the Protocols and other antisemitic propaganda. The Swiss Jewish community and the Jewish Community of Berne filed a criminal complaint under a Swiss law prohibiting the distribution of obscene literature. The case hinged on whether the Protocols constituted criminal obscenity under Swiss law.

The proceedings lasted from October 1934 to May 1935, across multiple sessions. The court heard extensive testimony from expert witnesses, including historians, scholars of Russian affairs, and handwriting analysts. The evidence presented was exhaustive: the documented plagiarism from Joly and Goedsche, the historical context of the document's creation, testimony about the Okhrana's propaganda methods, and detailed analysis of the text's internal contradictions.

On 14 May 1935, Judge Walter Meyer delivered his verdict. In a detailed written judgment, Meyer systematically demolished every claim to the Protocols's authenticity. He documented the extensive plagiarism from Joly. He noted the historical impossibilities and anachronisms riddling the text. He identified the document's obvious propagandistic purpose. He condemned it as "forgeries, plagiarisms, and obscene literature" and ruled it illegal to distribute in Switzerland.

Meyer's language was unusually forceful for a judicial opinion. He wrote:

I hope the time will come when nobody will any longer comprehend how in the year 1935 nearly a dozen fully sensible and reasonable men could for two weeks torment their brains before a Berne court over the authenticity or lack of authenticity of these so-called Protocols, these Protocols which, despite the harm they have caused and may yet cause, are nothing but ridiculous nonsense.

The judge recognised he was witnessing something historically absurd and morally appalling. Educated men in a modern courtroom, in the middle of the 20th century, were seriously debating whether an obvious forgery plagiarised from 19th-century sources might nonetheless be authentic. The very fact such a trial was necessary revealed how deeply the poison had spread.

The defendants appealed. A higher court partially overturned Meyer's ruling on a technicality, finding the Protocols did not meet the specific Swiss legal definition of obscene literature. However, the appellate court explicitly did not dispute Meyer's findings regarding the document's fraudulent nature.

The Protocols was indeed a forgery and plagiarism. It simply did not technically violate that particular statute. This legal technicality did nothing to rehabilitate the document's credibility.

The Era Of Extermination

Despite all the evidence, despite The Times exposure and the Berne judgment, the Protocols found its most enthusiastic and deadly champion in Adolf Hitler and the Nazi movement. For the Nazis, the document was far too useful to abandon merely because it was demonstrably false.

Hitler explicitly cited the Protocols in Mein Kampf, his political manifesto written while imprisoned following the failed 1923 Beer Hall Putsch. He wrote:

To what extent the whole existence of this people is based on a continuous lie is shown incomparably by the Protocols of the Wise Men of Zion, so infinitely hated by the Jews. They are based on a forgery, the Frankfurter Zeitung moans and screams once every week: the best proof that they are authentic... For once this book has become the common property of a people, the Jewish menace may be considered as broken.

The fact Jews and their defenders called the Protocols a forgery proved its authenticity. The more vehemently it was denied, the more certainly it must be true.

This is the reasoning of the paranoiac, where all evidence against the conspiracy merely proves how powerful and far-reaching the conspiracy must be. Counter-evidence becomes evidence. Denial becomes confirmation. The system is hermetically sealed against reality.

Nazi Germany made the Protocols required reading in schools. Children were taught its claims as historical fact. The document featured prominently in Julius Streicher's virulently antisemitic newspaper Der Stürmer. It appeared in Nazi propaganda films. The regime presented the Protocols as the key to understanding world history, politics, economics, and culture. Everything could be explained by reference to this Jewish conspiracy.

This propaganda campaign had a purpose beyond merely spreading hatred. It prepared the German population to accept, support, or at least ignore the systematic destruction of European Jewry. If Jews were genuinely engaged in a vast conspiracy to destroy Christian civilisation, then extreme measures against them could be framed as necessary self-defence.

The Protocols provided pseudo-intellectual cover for genocide, allowing ordinary Germans to convince themselves the extermination of their neighbours was somehow justified.

The document did not create antisemitism but it systematised and modernised antisemitic thinking for the 20th century. It transformed diffuse prejudice into a seemingly coherent worldview. It made mass murder thinkable by casting it as self-defence against an existential threat. Like Charlie Kirk's murder.

The Protocols did not operate the gas chambers or organise the death squads, but it helped create the mental universe in which such atrocities became possible. This is not a metaphor or exaggeration. This is documented historical causation.

Emigrés, Believers, and Eventual Rejection

Britain's relationship with the Protocols was complex and revealing of broader currents in early 20th-century British society. The document arrived in Britain through White Russian émigrés fleeing the Russian Revolution and subsequent Civil War. These refugees, members of the old Russian aristocracy and military officer class, were desperate to explain their catastrophic defeat. The Protocols provided a convenient explanation: they had not been beaten by superior forces or popular revolution but betrayed by a hidden conspiracy.

British conservatives, alarmed by the Bolshevik Revolution and fearing similar unrest at home, were predisposed to believe in revolutionary conspiracies. Britain had experienced significant labour unrest in the years before and after the First World War. The 1926 General Strike would nearly bring the country to a standstill. To some in the British establishment, the idea of a coordinated international revolutionary movement seemed plausible, and the Protocols appeared to offer documentation.

The Morning Post, a conservative London newspaper, serialised the Protocols in 1920 with commentary by its correspondent Victor Marsden, who had translated the document from Russian. Marsden had witnessed the Russian Revolution firsthand as the Morning Post's Petrograd correspondent, been imprisoned briefly by the Bolsheviks, and developed an intense hatred for the revolutionary regime. His translation came with lengthy anti-Jewish commentary, and he devoted the remainder of his career to promoting the Protocols before his death in 1920.

Other British publications followed suit. The Spectator gave it serious consideration. Even The Times, before Graves's expose, had treated the document as potentially worthy of investigation. Several prominent Britons, including some members of the aristocracy, initially took the Protocols seriously or at least found its claims worth considering.

However, British intellectual culture also contained countervailing forces: the empirical tradition, respect for evidence, and legal standards of proof all worked against the Protocols. When confronted with documented plagiarism and demonstrated forgery, significant portions of British opinion turned decisively against the document. The Times's exposure proved particularly important because it allowed those who had been uncertain or privately sceptical to openly reject the Protocols without being accused of naïveté or insufficient anti-Bolshevik zeal.

Our experience illustrates something crucial: propaganda succeeds best where it confirms existing beliefs and serves present political needs, but it can be countered by rigorous investigation and commitment to evidence.

Britain in the 1920s contained both antisemitic prejudice and intellectual traditions favouring empiricism. When these forces came into conflict over the Protocols, empiricism won, at least officially. This victory was neither inevitable nor complete, but it mattered.

The Mechanics of Persistent Belief

The forensic evidence against the Protocols has been overwhelming and publicly available since 1921. Yet the document continues to find believers more than a century later. It circulates in various countries, in multiple languages, distributed through conventional publishing and on the internet. New editions appear regularly. Believers cite it as authoritative. Why does such an obviously fraudulent document retain any credibility whatsoever?

The answer lies in the psychology of conspiracy thinking and the political utility of the Protocols for certain movements and ideologies. The document succeeded initially and persists today because it tells people what they already believe or want to believe. In societies where antisemitism already exists, the Protocols provides a pseudo-intellectual framework for existing hatred. It transforms inchoate prejudice into a seemingly coherent worldview, elevating raw bigotry to the status of political analysis.

Just how gender theory works.

Conspiracy theories function by providing simple explanations for complex phenomena. Rather than grapple with the genuine complexities of modernisation, industrialisation, economic disruption, and political change (phenomena without clear villains or simple solutions), believers can attribute all social ills to a single malevolent force. This is psychologically comforting.

Complexity is frightening. Acknowledging events might be chaotic, causation might be diffuse, and solutions might be difficult requires confronting human limitation and uncertainty. Far easier to believe powerful conspirators control everything, for this implies someone is in charge, even if they are evil.

The Protocols also benefits from what researchers call the "kernel of truth" fallacy. Believers claim the document must contain "some truth" because certain predictions supposedly came to pass. This reasoning is entirely backwards. The document was written by people living in the early 20th century, observing actual political trends. Of course some of its "predictions" about modern political developments seem prescient—they were describing contemporary or recent events, not prophesying the future.

Moreover, the predictions are so vague and general they can be retrofitted to almost any historical development. The Protocols speaks of controlling press and finance, promoting democracy to weaken monarchies, fomenting unrest, and advancing revolutionary movements. These are such broad categories almost any modern political event can be interpreted as fulfilling them. This is the same technique used by Nostradamus enthusiasts and astrologers: make predictions sufficiently vague, and some will inevitably seem accurate in retrospect.

Believers also employ motivated reasoning, consciously or unconsciously seeking to confirm what they already believe while dismissing contradictory evidence. When confronted with proof the Protocols is plagiarised from Joly, believers suggest this merely shows how clever the conspiracy is, producing fake sources to discredit genuine revelations. When reminded Jewish people themselves vehemently deny any such conspiracy exists, believers treat this denial as further evidence of the conspiracy's existence. The conspiracy theory becomes unfalsifiable, a closed loop of reasoning admitting no contrary evidence.

For certain political movements, the Protocols proves too useful to abandon despite overwhelming evidence of fraud. The document provides pseudo-legitimacy for antisemitism, allowing believers to claim their hatred is not mere prejudice but justified response to documented threat. It creates permission structures for violence, casting aggression as defence. It mobilises followers and provides a common enemy. These political utilities ensure the Protocols will continue circulating so long as antisemitism persists and political movements find scapegoating Jews advantageous.

The Contemporary Legacy

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion did not disappear with the defeat of Nazi Germany. It continues circulating in the 21st century, adapted to new contexts and distributed through new media. In various Middle Eastern countries, editions of the Protocols are readily available in bookshops, sometimes presented as factual documentation. Some political movements opposing Israel or Zionism cite the Protocols as evidence, seemingly unaware of or indifferent to its origins in Tsarist Russian antisemitism.

The internet has provided new distribution channels. Websites promoting various conspiracy theories frequently feature the Protocols, often presented without historical context that might alert readers to its fraudulent nature. New generations encounter the document with no knowledge of its thorough debunking, no awareness of the plagiarism, trials, and scholarly consensus exposing it as forgery.

The Protocols has also mutated, adapted to contemporary concerns. Some conspiracy theories borrow its structure and logic while substituting different villains. The "New World Order" conspiracy, the "Illuminati," various theories about global financial manipulation—all echo the Protocols's basic template of hidden elites manipulating world events. The specific villain may change, but the underlying logic remains the same.

This persistence demonstrates an uncomfortable truth: evidence and reason, whilst essential, are not always sufficient to overcome prejudice bolstered by motivated reasoning and political utility. The complete exposure of the Protocols as a forgery has not killed it because its believers do not actually care whether it is authentic. What matters is whether it is useful.

This Stupid Bullshit Never Goes Away

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion represents a comprehensive case study in how a demonstrable lie can persist despite overwhelming evidence of falsity. Every aspect of the document has been forensically dismantled. It is plagiarised almost entirely from earlier, unrelated sources. It is contradictory internally and logically incoherent. It contains anachronisms rendering its purported origins impossible. It has been legally condemned by courts as forgery after thorough examination. Its creation by the Tsarist Okhrana for specific political purposes is documented. Every claim to authenticity has been demolished. Every "prediction" has been explained. Every supposed proof has been refuted.

Yet it persists because it serves the psychological and political needs of antisemites who require a framework for their hatred. This persistence demonstrates why forensic examination of such forgeries matters immensely. Exposing lies in minute detail, documenting plagiarism line by line, dismantling false claims piece by piece may not convince the committed believer. The conspiracy theorist who has built his identity around such beliefs will find ways to dismiss any evidence, no matter how conclusive.

But forensic truth-telling serves other vital purposes. It arms reasonable people with evidence to reject such poison. It prevents new generations from falling victim to old lies. It establishes historical record against those who would distort it. It demonstrates respect for truth as a value worth defending. It honours the memory of those murdered because of lies.

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion is not a mysterious document requiring interpretation or an ancient text whose authenticity remains debatable. It is a proven forgery, created by known individuals, for documented political purposes, plagiarised from identifiable sources, and thoroughly debunked by courts, scholars, and journalists. Treating it as anything other than malicious fraud is not a matter of open-mindedness or alternative viewpoints. It is rejection of evidence, reason, and human decency.

The document contributed directly to genocide. This is not hyperbole. The Protocols helped create the intellectual and psychological conditions making the Holocaust possible. It provided rationalisation for persecution. It transformed neighbours into enemies and murder into self-defence. Six million deaths are part of its legacy, along with countless pogroms, attacks, and acts of violence across more than a century.

Philip Graves, writing in The Times a century ago, believed exposing the plagiarism would end the matter. Judge Meyer in Berne hoped his verdict would end rational debate about the document's authenticity. Both men underestimated the tenacity of hatred and the political utility of convenient lies. Yet both made vital contributions, establishing truth in permanent record where it can be found by anyone genuinely seeking it.

The fight against the Protocols is ultimately the fight for truth itself, for the principle evidence matters and falsehood can be definitively exposed. In this fight, there can be no neutrality. The forensic evidence is complete. The verdict is clear. The Protocols is a vicious, dangerous fraud, and must be named as such unambiguously and repeatedly, for as long as it continues poisoning minds.