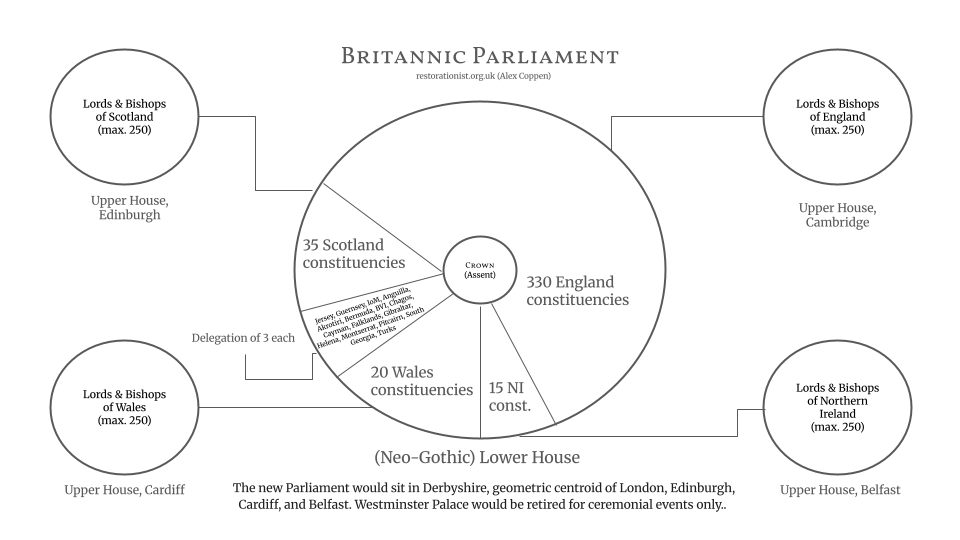

The Britannic Parliament

A beautiful new neo-Gothic Parliament for the 21st Century would sit at the geometric centroid of the four nations, re-bound politically under the Crown with the 17 territories for decision-making. Each would preserve their own devolved upper house to revise legislation for regional concerns.