The British Nationality Reset: The BINCA Bill

A new nationality system (BINCA) would legally distinguish indigenous British peoples from naturalised citizens, create citizenship denominations based on pre-1947 ancestry, restrict high offices, and use algorithmic reviews to assess loyalty for conditional citizenship holders.

Most people in England assume that somewhere in the statute book, or identified on his passport, the "Englishman" is acknowledged as a distinct political subject in law. He is not. Likewise, Scottish secessionists and unionists alike may believe the existence of the Holyrood devolved parliament proves the law recognises Scots as a people. It does nothing of the sort.

Under the British Nationality Act 1981, every one of us is simply "British." In the eyes of the Home Office, an Englishwoman whose family can trace its parish-register line back to the Dissolution of the Monasteries is legally indistinguishable from someone who has spent five years on a low-skill work visa, obtained indefinite leave to remain (ILR), and then opted to pass a short naturalisation ceremony (introduced by the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002) after completing a trivia test. These tests have been known to ask such things as the date of Eid.

Like all Labour's follies, nationality in Britain fell pray to reification fallacy: the concrete, empirical anglo individualist notion of belonging to the land through the cycle of birth/marriage/death was conflated with the rootless European-style abstract idea of "British."

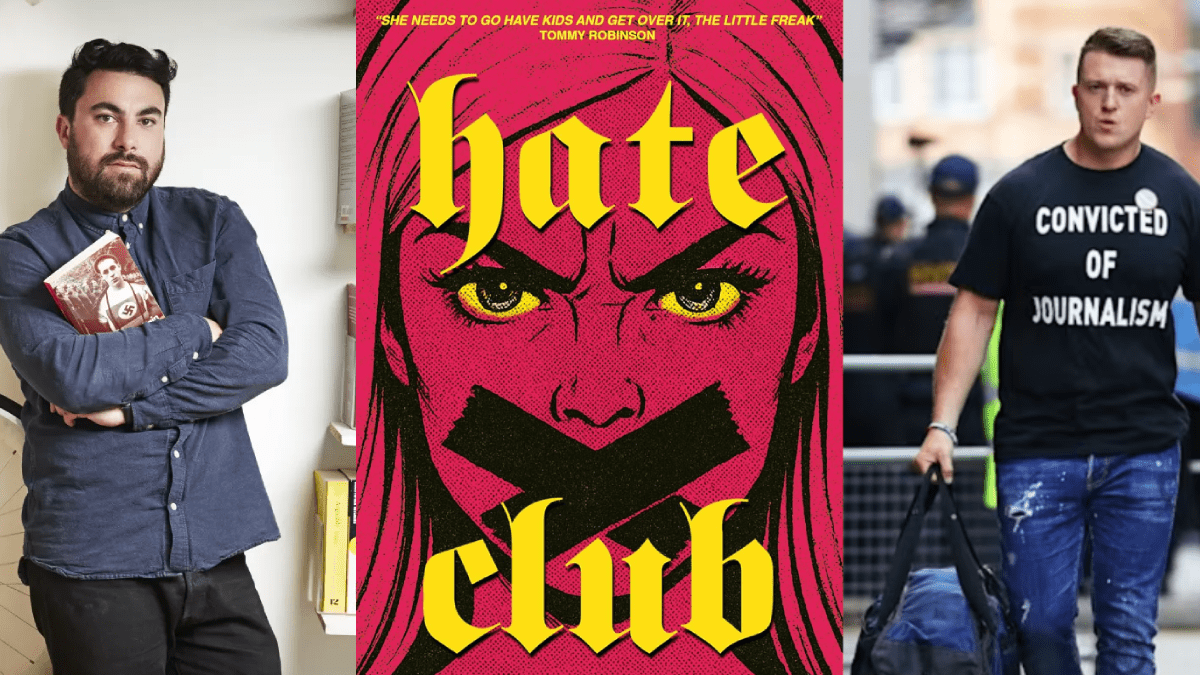

An Unsettling Discovery About Who We Are

The "Life in the UK" test, introduced in 2002, is widely criticised for its oddly foreign and arbitrary content, with examples ranging from questions on Eid al-Fitr to Diwali. The test can also be gamed: in a high-profile case, Josephine Maurice, a 61-year-old woman, was sentenced to four and a half years in prison after impersonating 13 different individuals to fraudulently sit the test on their behalf using wigs, disguises, and false identity documents.

The equivalence between indigenous people to these isles and ILR holders is not benign cosmopolitanism.

This wilderness of legal certainty is troubling enough on a personal level, as with Sunak, but catastrophic on a wider demographic level with respects to our border, and citizenship. Our author Charlie Cole detailed the starling demographic shifts which laxity in the realm of ILR and citizenship have produced in the passing decades. It is primarily stemming from the alteration of asylum and nationality acquisition: the Immigration & Asylum Act (1999) and Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act (2002).

Coupled with the Human Rights Act (1998), Blair imposed on us as system which obliged asylum seekers and visa-workers to have the option become citizens after a mere 5 years of presence. As per the July 2025 data, by 2030 the ethnic group which has occupied these islands for millennia will become a minority in births by 2030, and a minority in schools by 2035. We essentially have 1 (one) election to begin a legal reversal of who is and is not a citizen.

Given this urgency, The Restorationist is already drafting the legislation necessary.

Our proposed British Identity, Nationality and Commonwealth Bill (“BINCA”, once it becomes an Act – to be pronounced “Binn-Ka” for ease) aims to restore legal recognition to the peoples who, in reality, built our country while devising a fair, transparent system for guests and newcomers. It also offers a hi-tech approach to square the circle of the 20th and 21st centuries’ worth of border and citizenship chaos.

A Short History Of Legislative Drift

Firstly, it is worth noting "citizenship" itself is a relatively modern concept. Thomas More, Lord Chancellor to Henry VIII, first described the concept of a lord-granted passport which would be internationally recognised if retainers moved around in the 16th century. It would not be until the 19th that this became common between nation states.

Modern British nationality and citizenship law began as an exercise in improvisation.

In the medieval and early modern period, people were primarily subjects of monarchs rather than citizens of nations. Identity was tied to feudal relationships, local communities, or religious affiliations. One belonged to whoever ruled the land one lived on, and allegiance was personal to the monarch rather than to an abstract state. When a person traveled, they carried letters of introduction or safe passage from local authorities rather than standardised documents proving national belonging.

The modern nation-state system developed after the Peace of Westphalia (1648) but citizenship formalisation lagged behind. People increasingly identified with emerging national identities, but legal frameworks remained inconsistent. Different countries had wildly different approaches - some based on birthplace, others on bloodline, many with no clear system at all.

The British Nationality Act 1948, an inelegant Atlee-era creation, tried to retrofit an imperial notion of “subject-hood” to a post-war Commonwealth that was already dissolving like wet tissue paper. In place of the organic, territorially rooted allegiance which had existed for centuries, Parliament created the catch-all abstract status Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies (CUKC) and proclaimed every Commonwealth citizen a quasi-national. The right to belong floated free of any guaranteed right to enter or reside in the British Isles, and the ancient distinction between the natural-born subject and the naturalised stranger disappeared from statute.

We still retain some of this awkwardness today, certain citizens of the 83 commonwealth countries are allowed to vote in our elections without the need for citizenship – merely some form of residence. Not to mention, our monarch appears more concerned with his subjects in the wider commonwealth than the English throne he sits upon.

By 1981 legislators conceded that the 1948 post-colonial settlement was unworkable, but their cure merely reframed the problem. The British Nationality Act 1981 collapsed the various post-imperial categories of citizenship into the single label British citizen while severing that label from an automatic right of abode. What looked neat on paper masked a deeper problem: nationality had become an administrative convenience, not a constitutional bond.

The combined effect of 1948 and 1981 is now plain. The law still treats the English, Scots, Welsh and Ulster peoples as legally indistinguishable from any passport holder from anywhere in the world. A person born yesterday to two temporary residents may enjoy precisely the same citizenship as someone whose lineage is etched in parish registers back to Domesday. Another consequence of the post-colonial settlement is that the wider Anglo-diaspora families (who carried Anglo-British identity to Canada, Australia, New Zealand and many other places) often found themselves locked out of the country that once claimed them as kin.

The British Citizenship and National Integrity Bill 2025 (BINCA) begins with that diagnosis. It recognises the 1948 Act disrupted the continuity of ancestral and civic belonging and that the 1981 Act papered over, rather than resolved, the resulting contradictions. BINCA therefore proposes a fundamental reset.

Naming The Native Peoples In Law

Devolution in 1998 acknowledged the United Kingdom contains four historic nations. Yet nationality law still pretends the indigenous and ethnic peoples of those nations do not exist. As Tom Rowsell discussed here, modern English people range from 25-47% Anglo-Saxon (CNE), 11-57% Iron-age Briton (WBI), and 14-43% French (this last one is shocking). Though there is credibility to the idea that we are all an admixture, the specifics of that admixture was stable prior to the 20th and in particular, 21st century influxes of alien groups.

BINCA remedies the issue by creating two permanent statuses anchored in descent inside the British Isles:

- Indigenous British Citizen covers anyone born in the UK with at least one parent—or two grandparents—who could have passed a 1947 lineage test.

- Example: anyone with two grandparents in England, Scotland, Wales, or Northern Ireland having birthdays before 1947.

- Hereditary British Citizen extends the franchise to children and grandchildren of Indigenous citizens (by the method above) born either in the UK or in a Recognised State such as Canada or Australia, subject to a Swiss-style assimilation test (the Swiss are exceptionally good at these, we are not).

- Example: a Canadian, American, Australian, New Zealandian, or South African with an expat British mum or dad.

When it comes to identifying whether a parent or grandparent is able to confer the status of Indigenous or Hereditary British Citizenship, this would require that:

They were born in England, Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland on or before the date of January 1 1947.

They held the status of “British subject by birth” (i.e., they were natural-born under the prevailing common-law rules), or would unquestionably have been entitled to that status but for record-keeping anomalies.

For clarity regarding the 1947 cutoff date, anyone whose birth or already-recognised status falls on or before the date of 1947 is treated as part of the historic, territorially continuous population of the British Isles. The same occurred on the eve of the 1948 British Nationality Act.

This approach mirrors the way Australia and Ireland set an ancestral cut-off (1900 and 1922 respectively) for their own descent-based citizenship schemes.

One would go further, and suggest that indigeneity may be confirmed in conjunction with at-scale hereditary testing – to prevent fraud. The viability of this was discussed at length by an anonymous PhD researcher here, in which such testing was discussed for the purposes of health monitoring.

The shift is constitutionally focused one, not ethnic. It restores the principle the political community, and the offices that govern it, arise from a continuous people with a definable home territory. Parliament once took that premise for granted; BINCA makes it explicit again. Essentially, BINCA should be able to accurately cast an appropriate James Bond via the same methodology.

The Precedent: Genetic Testing for Citizenship or Nationality

United States (Native American Tribes)

Several federally recognised tribes, such as the Cherokee Nation and Navajo Nation, govern their own citizenship criteria. Most rely on descent from individuals listed on historical rolls (e.g., the Dawes Rolls), often with blood quantum requirements. However, where documentation is absent or paternity is in dispute, some tribes permit or require DNA testing to establish a biological link. This is typically used to confirm parentage rather than ethnicity. Tribal membership carries political and legal rights, including access to federal programs, and is considered a sovereign determination.

Israel

Under the Law of Return (1950), Israel grants citizenship to Jews and their descendants, including grandchildren. However, in disputed or marginal cases, particularly involving immigrants from Eastern Europe or Ethiopia, genetic testing has been used to verify claims of Jewish ancestry. This practice, though controversial, has appeared in conversion cases and aliyah applications, often at the request of rabbinical authorities rather than the civil state. The tests aim to confirm matrilineal descent or a genetic link to recognised Jewish populations.

Estonia (Emerging Model)

Estonia has not implemented genetic testing for citizenship, but it maintains a national genome project linked to its digital identity infrastructure. While not currently tied to nationality or immigration, academic discourse within Estonia has explored potential future applications of genomic verification in public policy. Estonia thus represents an early-stage precedent for integrating genetic and biometric data into state identity frameworks.

A Simpler, Clearer Citizenship Architecture

Everything outside the two permanent groups is reduced to three functional categories.

- Inherited Conditional British Citizen (ICBC) applies to UK-born descendants of post-1948 naturalised lines. The status grandfathers for two generations, is revocable based on strict criteria, and is reviewed (by algorithm, more on that later) every five years. An algorithmic review will either retain, review or revoke. It lapses after five years’ absence from the United Kingdom or her overseas territories, including crown dependencies.

- Example: immigrant parents from the 1960s, their children, and grandchildren.

- British Subject is a provisional route based on marriage to a citizen or historic naturalisation which brings an official document. It carries no right of transmission to children, suffers no processing delays, allows usage of the citizen lane, and can be revoked at any time.

- Example: a non-British husband or wife.

- Visitor means exactly that: presence of up to 180 days in any rolling twelve-month period. This does not confer, benefit or settlement rights and is automatically removed on suspected breach, notified or not. Outstaying this period without discretionary renewal is considered breach. Grounds for breach include the inability to support one’s life here.

- Example: anyone else born outside the UK.

Because BINCA abolishes discretionary naturalisation after commencement, the current lattice of points-based visas, investor routes, and ministerial waivers disappears. Employers, councils and migrants alike can navigate the system in one page, not a hundred.

Just as important, the bill re-opens a door that 1948 and 1981 silently closed. The Anglo-diaspora—families who left Britain when the Crown actively encouraged settlement overseas—regain a direct route home via the Hereditary form of citizenship, without having to queue behind temporary work-permit holders with no cultural tie to the country.

Anyone suggesting we require high-skilled workers from the global economy will be thrilled to learn that, in this instance, they will not even need to gain an immigration status – the Empire may now, properly, come home.

The Precedent: Citizenship by Parent or Grandparent Descent

Ireland

Irish nationality law allows individuals to claim citizenship if one parent was born in Ireland. In addition, those with an Irish-born grandparent can register on the Foreign Births Register and acquire citizenship by descent. This system is widely used across the Irish diaspora, particularly in the United States, Canada, and Australia. It is governed by the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956, reflecting a strong cultural commitment to ancestral connection.

Italy

Italy offers one of the most expansive jus sanguinis regimes in the world. There is no generational limit, provided the descent line remains intact and no ancestor formally renounced Italian citizenship. This has led to large-scale take-up among descendants of Italian emigrants, especially in Latin America. Italian courts have further clarified rights via the maternal line, especially for those born before 1948, in a series of recent precedents supporting gender equality in transmission.

Poland

Polish law allows descendants of former Polish citizens to claim nationality, often based on grandparent or great-grandparent status. Applicants must prove that their ancestor held Polish citizenship after 1920 and that no renunciation or naturalisation occurred elsewhere before a critical cut-off date. This route is used frequently by the Jewish diaspora and others with Central European ancestry.

Germany

Germany historically restricted descent-based citizenship but relaxed its rules in 2021 to accommodate the descendants of Nazi victims. Individuals whose ancestors were stripped of citizenship during the Third Reich can now reclaim it, even across multiple generations. Separately, regular descent-based citizenship applies to those with a German parent, but does not automatically extend to grandchildren unless special circumstances apply.

Integrity Reviews Founded On Evidence, Not Sentiment

The bill treats citizenship as a covenant which presumes contribution and good conduct. Every ICBC and British Subject therefore undergoes a five-year audit calculated by algorithm; We call it the National Integrity Assessment Formula, one such example is here:

S = (T × 4) + (A × 5) + (N × 3) + (H × 2) – (C × 5) – (R × 8) – (L × 3) – (DP × 2) + (X × 3)- Positive factors reward tax paid, assimilation, pre-1949 lineage and character affidavits.

- Negative factors penalise criminality, security risk, welfare dependence and public-order debts.

- Frequent returns to countries of security concern or notable cultural distance can also be factored in.

- Scores below zero trigger automatic loss of status and voluntary removal; scores between zero and nine prompt discretionary review; ten or more retain the status until the next audit.

These controls are not a form of social credit score, apply only to conditional status changes related to nationality, and are constrained entirely to non-indigenous/non-hereditary citizens.

For the numerically wary, a subtractive model could be employed along the same lines: every adult starts at 100 points and loses points for each negative indicator, with deprivation below 40. Either model restores a principle once summed up in six words: loyalty confers rights; disloyalty forfeits them.

The Precedent: Algorithmic or Discretionary Citizenship Review

Estonia

Estonia’s digital governance infrastructure tracks every resident’s interaction with the state, including tax contributions, military service, and social integration. While it does not currently use this data for citizenship review, the system allows for such a possibility. The country's X-Road platform integrates personal and biometric data in a way which could feasibly support a scoring model or national integrity review system in future.

United Arab Emirates

The UAE does not offer citizenship by birth or long-term residency. Instead, it reserves naturalisation for select foreigners deemed beneficial to the state. Candidates include scientists, investors, or skilled professionals. The process is highly discretionary and based on review by a national security committee. Citizenship can also be revoked for vaguely defined offences including disloyalty or reputational harm to the state. The criteria are unpublished, but rely on close monitoring of applicants’ economic contribution, loyalty, and connections.

Saudi Arabia

In 2021, Saudi Arabia opened a discretionary naturalisation process for foreign experts in law, medicine, and religious scholarship. As in the UAE, the vetting process is secretive and applicants are typically proposed by senior officials. Citizenship is revocable, with no appeal rights, especially if individuals fall afoul of the Kingdom’s moral or political expectations. There is no formal algorithm, but the process resembles utility-based state vetting.

Approximately 55.6% of Saudi Arabia’s population are Saudi nationals (around 20.5 million people), while 44.4% (around 16.41 million) are non-Saudis—overwhelmingly foreign workers and resident expatriates.

In practice, foreign nationals dominate the private-sector workforce, making up around 56.5% of employees; in certain industries, such as construction and domestic work, the share can be as high as 80–90% or more among non-Saudis. These workers will certainly not be entitled to become full citizens after a mere 5 years, as is the case in Britain.

Israel

Israel employs a formal deposit system for asylum seekers and certain foreign workers that serves multiple regulatory purposes. Under the so-called “infiltrator” regime (permit category 2(a)(5)), employers are required to divert 16% of the worker’s Israeli salary into a state-managed escrow account. These funds, held in designated accounts at Mizrahi Tefahot Bank, act as a pseudo-pension and discourage overstaying: the asylum seeker receives the deposit (minus tax and fees) only upon departure and only if they do so within the stipulated timeframe.

Additionally, Israel may require bank guarantees or deposits from foreign visitors or group visa holders. For instance, agents applying for visas from restricted countries must lodge significant sums (e.g., NIS 200,000) as a condition of issuance or compliance with border control rules. These mechanisms provide financial leverage to ensure visitors or workers do not overstay, and serve as a form of control aligned with national interest. Our Home Office has much to learn here.

The Cultural Distance Test

The Home Office will maintain a statutory list—Schedule B or C of the Act – of those countries possessing a "substantially different" culture from the United Kingdom. This is not intellectually difficult, but it could be highly susceptible to political manipulation and bias. Safeguards against these are essential.

The metrics here would need to be objective, and could start with:

- Documented human rights violations in countries of origin

- Terrorism sponsorship designations

- Reciprocal citizenship rights with the UK

- Educational system compatibility

Is Pakistan “different” enough but India not? Does Rwanda’s violence stat trump Jamaica’s?

- Cultures anchored in non-Christian faiths, especially those with historical or ideological friction with Britain’s Christian tradition;

- Nations lacking Common Law or British-style governance (e.g. Rwanda’s civil law mishmash or Saudi Arabia’s theocratic code)

- Countries with chronic instability or high violent crime. Stats from UN crime reports could set a threshold (e.g., homicide rate 5x the UK’s).

- No colonial tie pre-1945/

A country would be added to the list if it hits two+ criteria.

The latest comprehensive data on UK immigration by country of origin comes from the 2021/22 Census (England and Wales) and ONS migration statistics. The foreign-born population in the UK was approximately 10.7 million in 2021/22 (16% of the total population), rising to an estimated 11.4 million by June 2023 per ad hoc ONS estimates. By mid-2024, net migration reached 728,000, with non-EU countries dominating inflows.

- India - Approximately 920,000 (2021/22 Census), with continued high inflows via work and study visas (e.g., health sector).

- Poland - Approximately 700,000, though EU net migration has declined post-Brexit.

- Pakistan - Approximately 630,000, with steady family and work-driven migration.

- Romania - Approximately 540,000, reflecting post-2007 EU expansion mobility, though slowing.

- Ireland - Approximately 500,000, stable due to historical ties and Common Travel Area.

- Nigeria - Estimated 300,000–350,000 by 2024, rising sharply via work and study routes.

- Italy - Approximately 300,000, with gradual EU decline offset by pre-Brexit settlers.

- Bangladesh - Approximately 280,000, consistent family-based inflows.

- Philippines - Approximately 250,000, growing via health and care worker visas.

- Germany - Approximately 240,000, stable EU legacy population.

This list reflects foreign-born residents as of 2021/22, adjusted for 2024 trends (e.g., Nigeria’s surge, EU declines). Exact 2025 figures are unavailable, but patterns suggest non-EU growth (India, Nigeria, Pakistan) outpacing EU origins.

Drawing on demographic data (e.g., Pew Research for religion), legal system classifications (e.g., CIA World Factbook), violence metrics (e.g., UNODC homicide rates), and historical records of British colonial influence, the resulting list prioritises countries with stark contrasts to UK cultural norms, even if they aren’t major immigrant sources. An example Schedule B:

- Saudi Arabia: Islamic theocracy, Sharia-based law, no Empire ties, moderate violence (repression-driven).

- Iran: Islamic republic, non-Common Law, no Empire history, high instability.

- Afghanistan: Islamic, tribal legal systems, no colonial link, extreme violence (war-torn).

- Somalia: Islamic, customary/Islamic law, minimal Empire contact, severe instability.

- Yemen: Islamic, non-Common Law, no Empire ties, high violence (civil war).

- Sudan: Islamic majority, mixed legal system (non-Common), post-1956 independence, chronic conflict.

- Pakistan: Islamic, partial Common Law but Sharia-influenced, post-1947 split, elevated violence.

- Iraq: Islamic, civil law with Islamic elements, brief mandate only, persistent instability.

- Syria: Islamic majority, civil law, no deep Empire ties, high violence (war).

- Libya: Islamic, civil/Islamic law, post-1945 independence, significant unrest.

- Algeria: Islamic, civil law (French influence), no British ties, historical violence.

- Morocco: Islamic, civil law, no Empire connection, moderate stability.

- Egypt: Islamic, mixed civil/Islamic law, brief protectorate status, periodic unrest.

- Bangladesh: Islamic, partial Common Law but post-1971 divergence, no direct Empire rule, moderate violence.

- Indonesia: Islamic majority, civil law (Dutch influence), no British ties, occasional instability.

- Mali: Islamic majority, civil law (French), no Empire link, high violence (insurgency).

- Niger: Islamic majority, civil law, no colonial tie, instability (terrorism).

- Chad: Islamic/Christian split, civil law, no Empire history, chronic conflict.

- Rwanda: Christian but post-genocide violence, civil law, no direct Empire tie, high historical instability.

- Democratic Republic of the Congo: Christian, civil law, no British colonial rule, extreme violence.

- North Korea: Atheist/Confucian, authoritarian system, no Empire link, repressive stability.

- China: Atheist/Confucian, socialist legal system, minimal Empire contact (Hong Kong aside), controlled stability.

- Vietnam: Buddhist/Confucian, socialist civil law, no British ties, historical conflict.

- Thailand: Buddhist, civil law, never colonised by Britain, moderate stability.

- Nepal: Hindu/Buddhist, mixed legal system, no direct Empire rule, low violence but culturally distinct.

Fifteen countries (1–15, plus Mali, Niger) are Islamic-majority, reflecting the prioritised religious divergence from the UK’s Christian heritage. Pakistan and Bangladesh, despite Commonwealth status, diverge post-1947/1971 with Islamic influence outweighing Empire echoes. Most lack British legal traditions, relying on civil, Islamic, or customary systems, amplifying distance (e.g., Saudi Arabia’s Sharia vs. UK’s Common Law).

High-conflict zones (Afghanistan, Somalia, Yemen) score heavily, as do historically violent states (Rwanda, DRC), contrasting with UK stability.

Nations like Morocco, Thailand, and Nepal never fell under British sway, unlike India or Nigeria, which retain cultural bridges (language, law). India (1.457 billion) and Nigeria (235 million) miss the cut—Empire ties and Christian/Common Law elements dilute their distance, despite size or violence in Nigeria’s case.

Only five Schedule B countries (20%) appear in the UK immigrant top 25:

- Pakistan (3rd, 630,000)

- Bangladesh (8th, 280,000)

- Nigeria (6th, 300,000–350,000)

- China (12th, 220,000),

- Sri Lanka (20th, 120,000—if substituted for Zimbabwe).

The following are known or reasonably inferred to exhibit high levels of criminality among their UK immigrant groups, based on prison over-representation, specific crime patterns, or European proxies:

- Pakistan: Clear over-representation in prison and specific offences (e.g., grooming gangs).

- Somalia: Over-represented relative to population; gang and violent crime links.

- Vietnam: High prison share (1.3% vs. small population); tied to drug crimes.

- Algeria: Over-represented in prison (0.7% vs. 0.05% population share); petty crime noted.

- Morocco: Moderate ove-rrepresentation; North African crime trends apply.

- Democratic Republic of the Congo: Some gang activity; over-representation relative to size.

- Afghanistan: Inferred from European data (e.g., Germany); UK specifics unclear but plausible.

Securing The Offices Of State

In 1701, the Act of Settlement barred naturalised subjects from wielding prerogative powers precisely because allegiance was considered inheritable, not contractual. The 1948 Act repealed that bar; the 1981 Act left the repeal untouched. BINCA reinstates the safeguard for the twenty-first century. Cabinet ministers, members of the Privy Council and senior judges must be Indigenous British Citizens. The clause is narrow yet profound: it reunites ultimate decision-making authority with an unbroken constitutional allegiance, restoring the link that once defined the crown-in-parliament.

It is an absurd situation that our nation allows non-citizens to vote, and, even ILR holders to run for office. Our fixation on inclusivity has become a matter of security concern, where the interests of others are put before the national interest.

One such example is the well-documented Islamic group operating in the Home Office, and much of Whitehall; The Civil Service Muslim Network is a cross-government staff network founded around 2007 to support Muslim civil servants, promote religious literacy, and act as a "critical friend" in policy discussions across departments. In March 2024 it was suspended following allegations network webinars instructed civil servants to lobby on Gaza-related policy and included antisemitic tropes; though later reinstated under new oversight following a government investigation that cleared most members.

Another is the emergence of Gaza Independent candidates, and subsequently Jeremy Corbyn’s breakaway group of Islamic pro-Gaza backbenchers, who actively seek to split the Labour Party in favour of foreign interests.

Earlier in 2025, around 20 British MPs, many of Indian or Pakistani origin (including Tahir Ali, Zubair Ahmed, Rosena Allin-Khan and Abtisam Mohamed and Stella Creasy – who is spiritually Pakistani) signed a public letter urging Pakistan's prime minister to build an international airport in Mirpur arguing it would serve over a million "British Kashmiris" living in the UK. Such advocacy does not reflect British national interests and is a dual allegiance syndrome issue which can, and should, easily be stopped.

The Precedent: Nativist restrictions on high office

It is hardly controversial to suggest the restriction of key offices to a preserved group. Many countries reserve their highest offices for citizens with deep ancestral or exclusive national ties. The U.S. Constitution limits the presidency to natural-born citizens; Australia disqualifies dual nationals from Parliament under Section 44; and countries like Ghana, Indonesia, and Israel impose birthright or ethnic lineage requirements for top state roles.

These rules reflect a shared principle: that ultimate authority should rest with those whose loyalty is rooted at home not just in law, but in inherited allegiance to the nation. No longer can Rishi Sunak claim that holding the office of Prime Minister is a credential in his (misguided) claim to be an ethnic Englishman.

Administrative Clarity And Fiscal Fairness

BINCA also resolves several long-running practical problems. First, it ends the confusion which arises when every public body must infer ethnicity or cultural attachment by proxy. The law itself will now state who belongs, who may belong by descent, and who is visiting. Second, it replaces today’s sprawling visa code with three transparent categories. The Home Office can redirect resources from adjudicating overlapping leave-to-remain applications to enforcing clear rules at the border.

Third, the bill closes a fiscal loophole. At present, a child born in Britain to two temporary residents may trigger a chain of family settlement, housing support and benefit entitlements even when neither parent has contributed a day’s tax. Under BINCA, only ICBCs—whose families chose naturalisation—would acquire citizenship by birth, and their status remains conditional on contribution.

Finally, by offering the Anglo-diaspora a streamlined Hereditary route, the bill ensures cultural continuity, not bureaucratic happen-stance, guides admissions. A Canadian grand-child of British war veterans will find it easier to settle than a stranger with no historic connection beyond a job offer from Uber, or at a cousin’s American Candy shop.

That hierarchy is not discriminatory; it is simply the return of coherent statecraft. Someone attending a job will not be unable, however, they will not be automatically waived into citizenship by the measure of time.

Why Now

No honest observer doubts the United Kingdom faces a convergence of pressures: record migration flows, a housing market at breaking point, court lists straining under immigration appeals, and a social contract fraying at both cultural and fiscal seams. Even parties who once championed maximal openness now concede the status quo cannot hold.

Yet tinkering at the margins—tightening a work-permit rule here, increasing a surcharge there—has failed before and will fail again. The root malfunction lies in a nationality code which neither distinguishes the native peoples, nor rewards genuine allegiance, nor deters opportunistic exploitation. BINCA removes those structural incentives. It does not promise to end migration, or to solve housing shortages overnight, but it would align the rules of membership with the enduring realities of community, contribution and capacity.

A Constitutional Homecoming

More than three centuries ago Sir John Knight told the Commons each generation holds the birth-right of English liberty on trust for the next (read more on that from John Hedgerow here.) The intervening centuries did not erase such an obligation; they merely obscured it in layers of imperial compromise and administrative tidiness. The British Citizenship and National Integrity Bill makes the duty visible again. It names the people who built the country, invites their descendants home, welcomes guests on transparent terms, and insists that allegiance must be lived, not claimed by default.

Critics will call the bill radical. In truth it is conservative in the precise sense: it conserves a constitutional logic which predates both empire and modern bureaucracy— a nation is a moral community grounded in descent, territory and mutual obligation. By codifying that logic in clear, modern language, BINCA restores citizenship to what it ought always to have been: a covenant of reciprocal loyalty between the state and those to whom it truly belongs.

If Parliament enacts the measure, Britain will have completed a task postponed since 1948: squaring the circle a once confused subject-hood with paperwork, and re-syncing legal nationality with lived national identity. The reward will be a citizenship worthy of its name: enduring, intelligible, and once again anchored in the people whose ancestors called this Realm home.