The Child Sexual Exploitation (Public Inquiry and Accountability) Private Members Bill

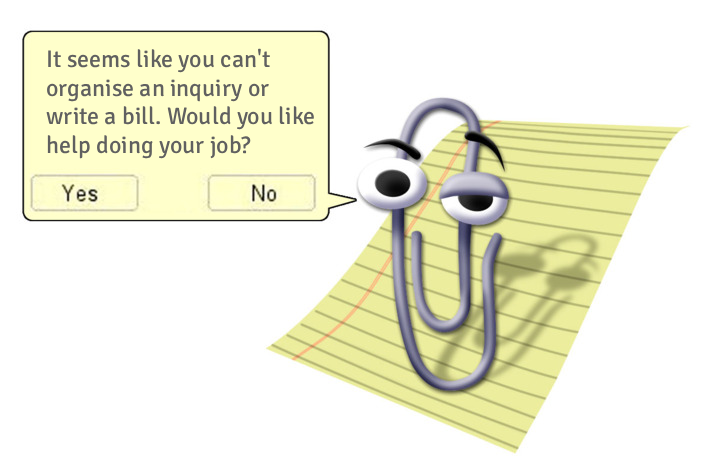

MPs across parties publicly support a rape gangs inquiry but write no legislation to create one. This bill establishes a statutory inquiry with compulsory powers, protected funding, and a nine-month timeline to deliver answers instead of Instagram selfies and PR gimmicks. Do your damned job.

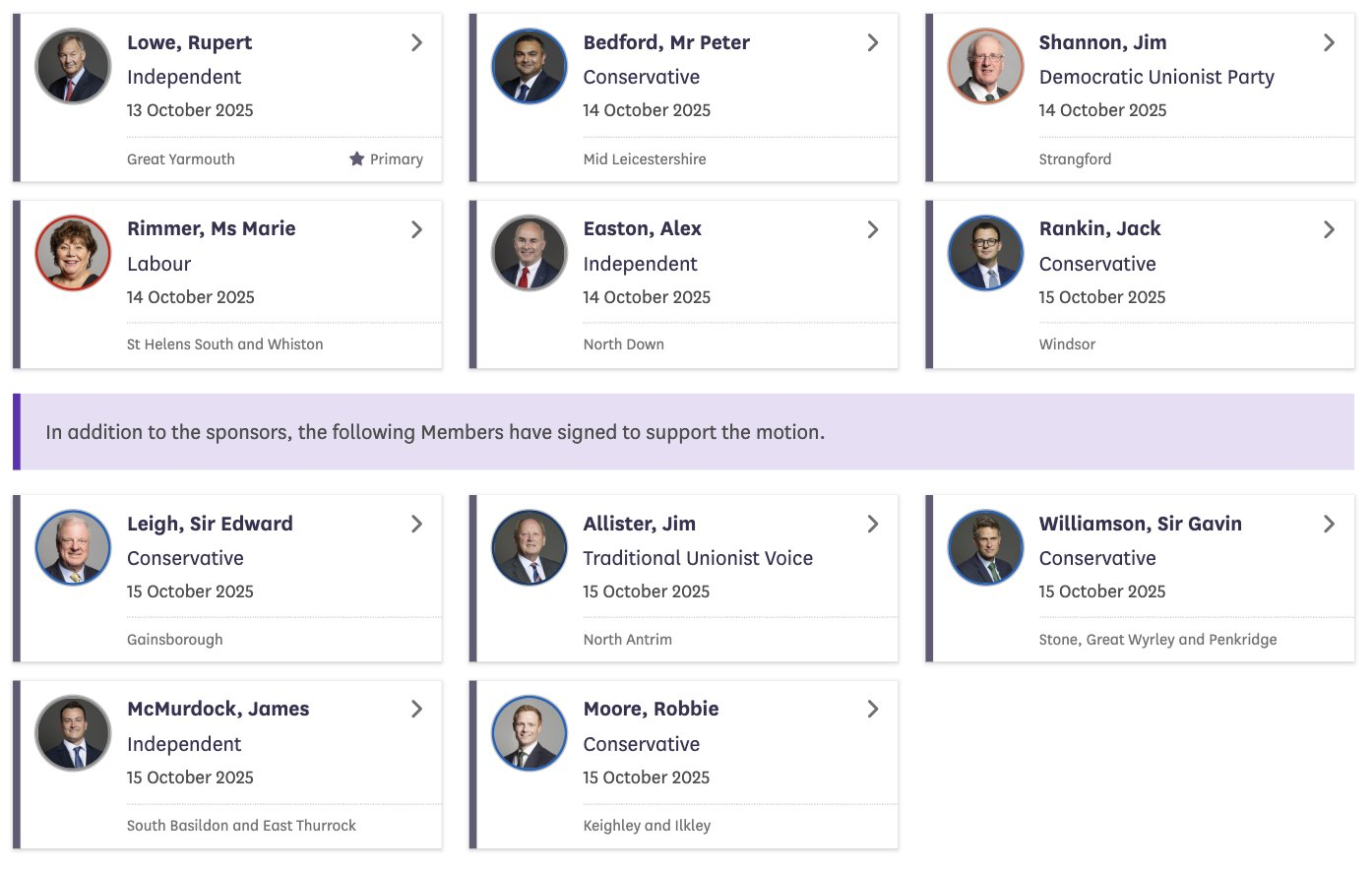

The image of elected representatives matters. When MPs from across the political spectrum publicly declare their support for an inquiry into one of the gravest institutional failures in modern British history, the public reasonably expects action to follow. Yet the list of names grows longer whilst the legislation remains unwritten.

Anti-Brexit withdrawal bills were passed in minutes with MPs literally running across the House floor.

This presents a peculiar situation. Members of Parliament—Conservative, Labour, Independent, and others—have attached their names to support for an inquiry into child sexual exploitation by organised grooming gangs. They have posed for photographs. They have issued statements. What they have not done, despite being employed specifically to draft and pass laws, is produce the actual legislation required to make such an inquiry happen.

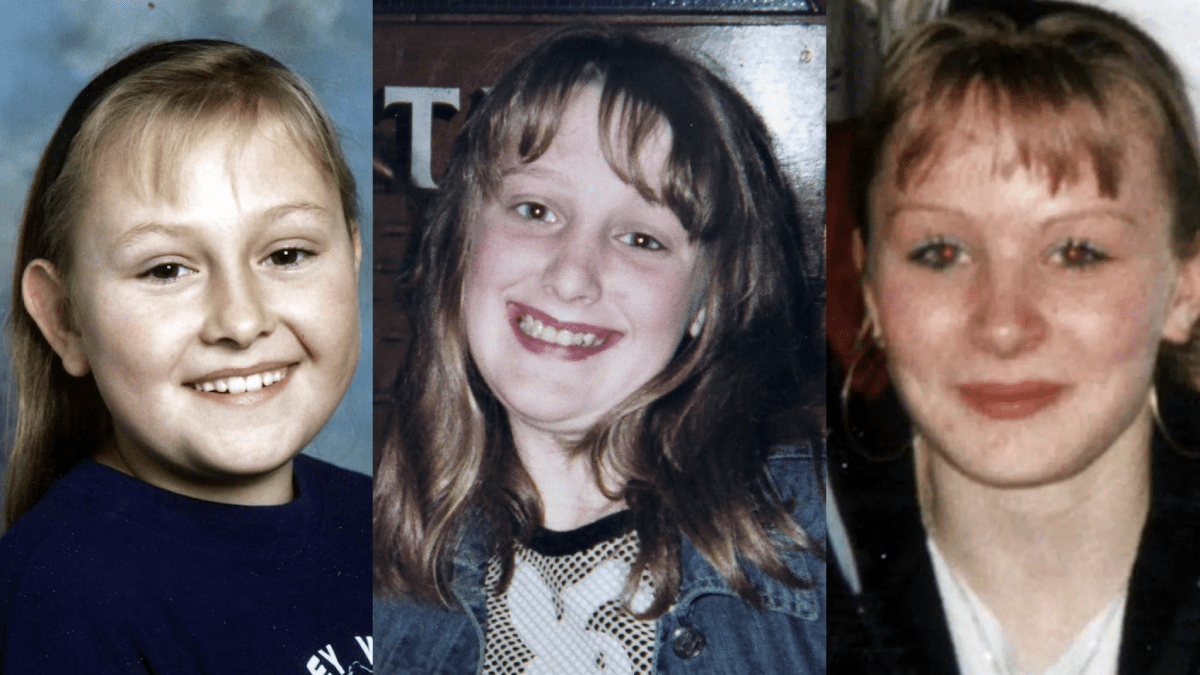

After five months, the government are conveniently unable to find a chair (and don't want to), as Rupert Lowe's "inquiry" increasingly reveals itself as a joke – one survivor's climb to the cover of Vogue magazine as a "best-selling author." The website is a joke; the "research" boasted of has not appeared; survivors who visited Parliament are complaining of being blocked on social media and interest only in "selfies"; the support of 1 single MP is being celebrated as a grandiose win, and more delays are pushing imaginary hearings back to next year.

None of them are taking this seriously or appear competent enough to organise the most basic drinking competition in a brewery, despite overwhelming public support to the tune of taxpayer funds or donations totaling almost £700,000. If you're in over your head, quit while you're ahead – this matters to people.

The bill presented here fills this void. It establishes a statutory public inquiry with compulsory powers, protected funding, and an accelerated timeline designed to deliver answers within nine months rather than the seven years consumed by the previous Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse.

Read the 27-page Child Sexual Exploitation (Public Inquiry and Accountability) Act in full below:

What Private Members' Bills Actually Are

Before examining what this bill does, it helps to understand the mechanism through which backbench MPs can propose legislation independently of the Government.

Under Standing Order 23 of the House of Commons, any Member may introduce a bill on their own initiative. These Private Members' Bills follow the same legislative process as Government bills—First Reading, Second Reading, Committee Stage, Report Stage, and Third Reading in the Commons, followed by consideration in the Lords—but they face significant practical constraints.

The most significant constraint is time. The Government controls the vast majority of parliamentary time, and Private Members' Bills compete for the limited slots available on thirteen Fridays during each parliamentary session. Without Government support, even popular bills can struggle to progress beyond their initial stages.

There are three main routes for introducing a Private Members' Bill. The Ballot, held at the start of each session, randomly selects twenty MPs who gain priority for their bills. These ballot bills receive the best chance of success, as they appear first on the limited number of sitting days.

The Ten Minute Rule, available under Standing Order 23, allows an MP to make a ten-minute speech proposing a bill before the House votes on whether to allow its introduction. This serves excellently as a platform to raise awareness of an issue.

The Presentation method requires no speech at all. An MP simply presents their bill to the House, and it joins the queue. These bills rarely become law without Government backing, but they place an issue formally on the parliamentary record.

Success rates tell their own story. Since 1997, only around 5% of Private Members' Bills have received Royal Assent. Most that succeed either address narrow technical matters or gain Government support along the way. Controversial or expensive measures face serious obstacles. Does that mean don't bother?

This reality explains why substantive reform often requires either Government initiative or such overwhelming public and parliamentary pressure to force Government adoption of a backbench proposal. The MPs pictured supporting an inquiry have the theoretical power to introduce this bill through any of these mechanisms. Whether they will remains another question.

What the Bill Actually Does

The Child Sexual Exploitation (Public Inquiry and Accountability) Bill runs to twenty-nine sections across six parts. Its structure follows proven inquiry models whilst adding mechanisms specifically designed to prevent the delays, cost overruns, and institutional resistance experienced by previous investigations.

Part 1 establishes the inquiry itself under the Inquiries Act 2005. This matters because it provides statutory authority rather than relying on non-statutory reviews, which lack compulsory powers. The inquiry receives a clear remit: examine the nature, scale, and extent of child sexual exploitation by organised grooming gangs across England and Wales; investigate why public authorities failed to act despite warnings; and recommend measures to prevent future failures.

The terms of reference direct the inquiry to answer three fundamental questions. What happened—the scale and locations of exploitation. How it happened—the methods and circumstances enabling it. Why it was allowed to happen—the systemic failures permitting exploitation to continue despite available evidence.

Within fourteen days of the bill receiving Royal Assent, the Secretary of State must appoint a panel of three to five members with expertise in child protection, criminal justice, institutional governance, and victim support. No panel member may have held senior positions in any public authority under investigation during the relevant period, which extends from January 1980 to the present day. This ensures the panel cannot be accused of investigating itself or protecting former colleagues.

Part 2 grants extensive powers. The inquiry can compel witnesses to attend and give evidence under oath, require production of documents, and prosecute failures to comply. Criminal penalties for non-compliance include up to two years imprisonment. The bill imposes an immediate data preservation duty on all relevant institutions, making destruction or alteration of records after commencement punishable by up to five years imprisonment.

These powers address a recurring problem in British public inquiries: institutional obfuscation. When bodies under investigation control the evidence, delay and selective disclosure become standard tactics. This bill flips the assumption. Evidence preservation becomes mandatory from day one, and deliberate destruction constitutes a serious criminal offence.

Part 3 structures the inquiry in three stages. Stage 1 commences within fourteen days of panel appointment and covers evidence collection. The inquiry publicly announces its existence, calls for written submissions within a sixty-day window, and reviews existing reports including the Jay Report and Casey Review.

Stage 2 begins within ninety days and consists of public hearings. These hearings will be livestreamed, creating a permanent public record whilst protecting vulnerable witnesses through remote testimony options, anonymity provisions, and support person access. Witnesses who fail to appear without reasonable excuse will have their absence noted in the livestream, with their expected questions read into the record. The inquiry can issue further summonses, refer matters for prosecution, name non-attending witnesses publicly, and draw adverse inferences from refusal to cooperate.

This approach addresses another common inquiry failure: allowing powerful witnesses to simply ignore summonses or provide inadequate answers without consequence. The combination of livestreaming, public naming of non-cooperation, and criminal penalties creates genuine accountability.

Stage 3 covers report compilation and publication. The panel must deliver its final report within six months, with a possible three-month extension for complex cases. The bill requires the report within nine months rather than allowing inquiries to stretch indefinitely.

Part 4 governs reporting requirements. The final report must identify persons and institutions responsible for failures where evidence supports such findings, recommend legislative and policy reforms, suggest measures for victim support, and record all instances of non-cooperation.

Before publishing criticism, the inquiry must provide advance notice and a reasonable opportunity to respond. This ensures procedural fairness whilst maintaining investigative rigour.

The bill includes a dedicated section on criminal referrals. Where evidence suggests criminal conduct—whether original exploitation offences or subsequent institutional concealment—the inquiry must refer the matter to the Director of Public Prosecutions with a recommendation on whether special prosecution arrangements are required.

The Secretary of State must lay the final report before Parliament within seven days of receipt and publish it the same day. Within fourteen days, the panel holds a public question and answer session, livestreamed and open to questions from the public, victims, and press. Within sixty days, the Government must respond to every recommendation, stating which it accepts, which it rejects, and providing reasons and timelines.

The bill creates ongoing accountability through the Victims' Commissioner, who must monitor implementation annually for three years and can require progress reports from implementing bodies. Where the Government accepts recommendations, it must publish detailed implementation plans within ninety days and progress reports every six months until completion.

Part 5 addresses funding and transparency. The Secretary of State must provide necessary funding for thorough investigation whilst keeping costs proportionate. The inquiry publishes quarterly financial statements showing all expenditure and recipients. Any unexpended funds return to charities supporting exploitation victims.

Legal representation for victims comes from the inquiry budget without means testing. This ensures survivors can participate effectively regardless of personal resources.

Part 6 covers general provisions including contempt powers, anonymity protections, and whistleblower safeguards. Contempt of the inquiry—including witness coaching, document destruction, false evidence, or intimidation—can be certified to the High Court for punishment as contempt of court.

Whistleblower protection extends for five years beyond the inquiry's conclusion, making dismissal or detriment actionable with mandatory compensation and possible reinstatement. The bill recognises past inquiries have suffered from witnesses fearing career consequences for truthful testimony.

The bill expires five years after Royal Assent unless continued by resolution of both Houses. This sunset provision reflects the understanding this inquiry addresses specific historical failures rather than creating permanent bureaucracy.

Learning From Inquiry Failures

The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, established in 2015, consumed seven years and over £186 million before concluding in 2022. It faced four chair resignations, scope creep, and widespread criticism for failing to deliver timely recommendations.

The infected blood inquiry, though ultimately valuable, took seven years from establishment to final report. The Post Office Horizon inquiry continues years after initiation, with compensation still pending for many victims.

These precedents demonstrate the danger of open-ended inquiries lacking clear timelines, defined scope, and robust cooperation mechanisms. Well-intentioned investigations become mired in procedural disputes, institutional resistance, and endless evidence gathering.

This bill imposes discipline. Six months for evidence and hearings, three months maximum extension, mandatory cooperation with criminal penalties for non-compliance, livestreamed proceedings preventing closed-door dealings, and immediate data preservation stopping evidence destruction.

The livestreaming provision deserves particular attention. Public inquiries often promise transparency whilst holding key sessions in private or publishing edited transcripts months later. Real-time public broadcast prevents this. When institutions know their answers will be heard immediately by the public, the quality of those answers improves markedly.

Similarly, the provision allowing the inquiry to read expected questions into the record when witnesses refuse to attend transforms absence from a delay tactic into an admission. The public hears precisely what questions the witness declined to answer.

The Question of Political Will

Technical excellence in legislative drafting means nothing without political will for implementation. The MPs pictured have publicly supported an inquiry. They now face a straightforward choice: introduce this bill through one of the available mechanisms or explain why they prefer continued inaction.

The ballot system offers the cleanest route for any MP drawn in the ballot who wishes to use their privileged position for this purpose. The Ten Minute Rule provides a platform for any MP to propose the bill and force a vote on whether to allow its introduction. Even the presentation method, though unlikely to result in law without Government backing, places the proposal formally before Parliament.

None of these routes guarantees success. The Government may oppose the bill on cost grounds, jurisdictional concerns, or simple preference for maintaining control over inquiry timing and scope. Opposition MPs may support the principle whilst declining to spend their limited parliamentary capital on the specific mechanism proposed.

These calculations are legitimate. What is not legitimate is signing up to support an inquiry whilst making no actual attempt to legislate for one.

The public is not naive. People understand political constraints and parliamentary procedure. What they struggle to accept is performative support without substance. If an inquiry is genuinely necessary—and the list of supporting MPs suggests cross-party agreement it is—then someone must actually draft the legislation, introduce the bill, and fight for its passage.

This bill exists. It provides comprehensive statutory authority for the inquiry MPs claim to support. It incorporates lessons from previous inquiries whilst adding robust mechanisms for compliance and timeliness. It protects victims, compels cooperation, ensures transparency, and delivers results within a defined timeframe.

The question now is simple. Will any of these MPs put their names to something more substantial than a photograph?