The Crown and Its Denizens

Contemporary anti-immigration campaigners fail to recognise their need to return to the ancient English customs they have never heard of. Before the modern practice of naturalisation, the English demarcated the honoured foreigner with a particular status and requirements.

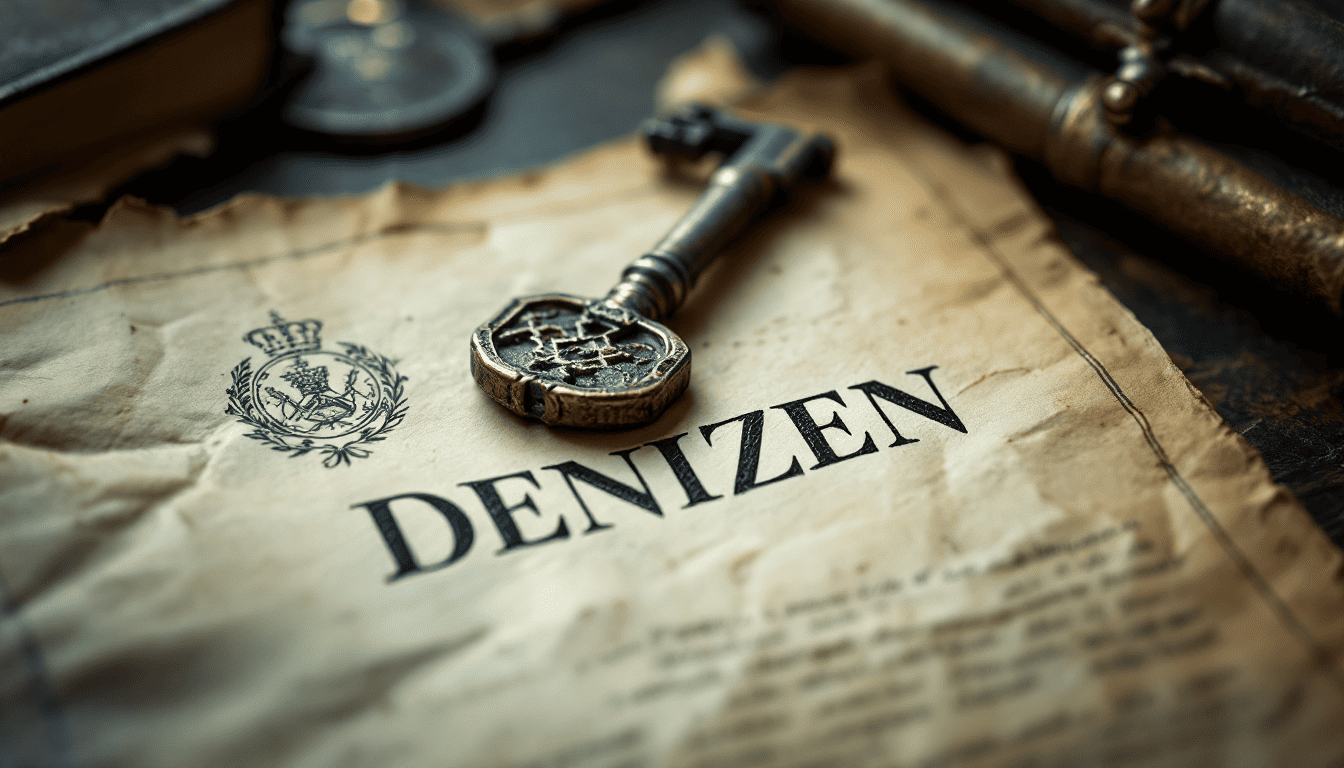

The concept of denizenship represents one of the most fascinating yet overlooked aspects of English legal history. For centuries, this unique status served as a crucial mechanism for integrating foreigners into English society while maintaining clear distinctions between native-born subjects and newcomers. Understanding denizenship provides essential insights into how nations historically managed immigration, citizenship, and belonging—questions which remain profoundly relevant today.

At its core, a denizen was a foreign-born person who had been granted special legal status by the English Crown, placing them in an intermediate position between an alien (foreigner) and a natural-born subject. This status emerged from practical necessity: medieval and early modern England needed foreign merchants, craftsmen, and skilled workers, but was reluctant to grant them full political rights. Denizenship offered an elegant solution to this dilemma.

Within, But Not From

The term "denizen" carries a rich linguistic heritage which reflects its legal significance. Derived from the Old French denzein or denzien, which itself stems from the Latin deintus meaning "within," the word literally translates to "one who dwells within." This etymology captures the essence of the status: these were people who lived within the realm but were not originally of it.

The concept emerged during the medieval period when England's legal system was developing sophisticated distinctions between different categories of inhabitants. As commerce expanded and religious conflicts drove waves of skilled refugees to English shores, the Crown needed a flexible mechanism to incorporate valuable foreigners without compromising the privileges of native-born subjects. By the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, denizenship had become a well-established legal institution.

The Three-Tier System of Legal Status

To fully appreciate denizenship, one must understand the tripartite division of people under English law as articulated by Sir William Blackstone in his influential Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765-1769).

First, there were aliens: foreign-born persons who owed no allegiance to the English Crown. Their rights were severely restricted. They could not own land except through special arrangements, were excluded from many trades and guilds, paid higher customs duties, and possessed no political rights whatsoever. Their presence in England was essentially at the Crown's pleasure, and they could be expelled at any time.

Second, there were natural-born subjects: those born within the King's dominions who enjoyed full rights and privileges under English law. These individuals could own land freely, engage in any lawful trade, participate in governance, and claim the Crown's protection anywhere in the world. Their allegiance to the sovereign was considered permanent and indissoluble, a debt of gratitude for the protection received from birth.

Third, occupying the middle ground, were denizens: foreigners who had received letters patent from the Crown granting them a subset of the rights enjoyed by natural-born subjects. This intermediate status reflected a pragmatic compromise between economic necessity and political caution.

The Process of Denization

Denization was exclusively a royal prerogative, meaning only the monarch could grant this status. The process began with a petition to the Crown, often supported by influential patrons or commercial interests. If approved, the Crown would issue letters patent under the Great Seal, formally transforming the alien into a denizen.

This process differed fundamentally from naturalisation, which required an Act of Parliament. While denization was quicker and relied solely on royal authority, it conferred fewer rights. Naturalisation, though more cumbersome and expensive, made the recipient legally equivalent to a natural-born subject in almost every respect.

The coexistence of these two pathways reflected the balance between royal prerogative and parliamentary power that characterised the English constitutional system.

The cost of obtaining denization varied but was generally substantial enough to limit it to merchants, skilled craftsmen, and others who could afford the fee or had sponsors willing to pay. This financial barrier ensured denization remained a selective process, reserved for those deemed economically or socially valuable to the realm.

Rights and Limitations of Denizens

The rights granted to denizens represented a carefully calibrated compromise. In terms of economic rights, denizens could purchase and hold land—a privilege denied to aliens. This was crucial for merchants establishing warehouses or craftsmen setting up workshops. They could also engage in trades from which aliens were excluded, particularly important given the guild system's monopolistic control over many occupations.

A denizen could not inherit land, as inheritance required "inheritable blood" only natural-born subjects possessed. Children born to a denizen before denisation could not inherit from their parent, though children born afterward could. This created complex family situations where siblings might have different inheritance rights.

Politically, denizens remained second-class citizens. They could not sit in Parliament, serve on juries in certain cases, or hold high offices of state. These restrictions reflected deep-seated concerns about foreign influence in governance—concerns which would resurface repeatedly throughout English history.

The prohibition on holding "offices of trust" extended to military commands, judicial positions, and membership in the Privy Council.

Commercially, while denizens gained access to domestic trade, they often continued to pay some of the higher customs duties imposed on aliens, particularly on imports and exports. This maintained a competitive advantage for natural-born merchants while still allowing denizens to participate meaningfully in the economy.

Political Exploitation of Immigration

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, religious persecution on the Continent drove waves of skilled Protestant refugees to England. The Huguenots fleeing France after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 provide perhaps the most dramatic example. These groups brought valuable skills in silk weaving, clock making, and other crafts. Denization allowed England to benefit from their expertise while maintaining legal distinctions between newcomers and natives.

In the American colonies, denization served a similar function, allowing colonial governors to integrate useful foreigners without waiting for parliamentary action thousands of miles away. This localised approach to immigration proved essential for colonial development, particularly in attracting non-English European settlers who could help establish frontier communities.

Granting denization to prominent foreign merchants or nobles could cement commercial or political alliances. Conversely, restricting or revoking such privileges could signal diplomatic displeasure. The Crown thus wielded denization as a tool of both domestic and foreign policy.

The Rivalry With Naturalisation

The institution of denization embodied fundamental tensions in English constitutional thought. On one hand, it represented royal prerogative—the monarch's traditional power to act independently in certain spheres. On the other, parliamentary supremacy increasingly demanded significant changes to subjects' rights require legislative approval. This tension contributed to the gradual replacement of denization with statutory naturalisation procedures.

Culturally, denization reflected and reinforced ideas about English exceptionalism and the special nature of English liberties. The careful gradations between alien, denizen, and subject suggested full membership in the English polity was a privilege to be earned or inherited, not simply claimed. This hierarchical view of belonging would profoundly influence how the British Empire later conceptualised citizenship and subjecthood across its global territories.

The requirement those seeking certain offices take Anglican communion—reinforced by the Test Acts—added a religious dimension to these distinctions. Even a denizen who sought higher office would need to conform to the established church, intertwining religious, political, and legal identity in complex ways.

The Decline and Abolition of Denizenship

The decline of denizenship began in the eighteenth century as Parliament increasingly asserted control over nationality questions. The Jewish Naturalization Act of 1753 (though quickly repealed due to popular opposition) marked a watershed in parliamentary engagement with naturalisation policy. By the nineteenth century, statutory naturalisation procedures had become more streamlined and accessible, reducing the need for royal letters patent of denization.

The Naturalization Act of 1870 represented a crucial step toward modern nationality law, establishing standardized procedures and reducing executive discretion. The British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1914 effectively ended denizenship as a meaningful legal category, though technically the royal prerogative to create denizens was not formally abolished until later reforms.

The Imperial Conference of 1911 and subsequent imperial legislation began creating a common imperial citizenship which transcended the old distinctions between subjects, denizens, and aliens within the British Empire. This process culminated in the British Nationality Act 1948, which established the modern framework of citizenship for the United Kingdom and its remaining colonies.

Do They Know Their Own Customs?

The concept of denizenship represents a fascinating chapter in legal history which illuminates enduring questions about membership, belonging, and the boundaries of political community. For nearly five centuries, this intermediate status served as a crucial mechanism for managing variety in English society, allowing the integration of valuable foreigners while preserving distinctions which were considered essential to social and political order.

Understanding denizenship requires appreciating both its historical specificity and its broader implications. It emerged from medieval and early modern England's particular circumstances but addressed universal challenges societies continue to face. How do we incorporate newcomers while maintaining social cohesion? How do we balance economic imperatives with political concerns? What rights and responsibilities should attach to different categories of residence and belonging?

As we grapple with these questions in our own time, the history of denizenship offers both cautionary tales and potential insights. It reminds us our current categories of citizenship and immigration status are neither natural nor permanent but rather products of historical development which will likely continue to evolve. Most importantly, it demonstrates societies have always struggled to balance inclusion and exclusion, universalism and particularism, in their definitions of membership and belonging.

The story of denizenship is ultimately about how societies define themselves through whom they include, whom they exclude, and what gradations of belonging they recognise. In studying this forgotten institution, we gain perspective not only on the past but on our present and future challenges in creating just societies.

While our modern firebrands advocate policies of mass deportation and remigration, they would do well to study their need to restore their ancestors' ways.