The Digital ID Nightmare: A Cybersecurity Expert's Warning

Digital ID isn't merely a cybersecurity catastrophe waiting to happen. It will do nothing to stop illegal immigration or illegal working, but will be abused as a political mechanism to revoke access to everyday things ordinary people need. As always, the cure is yet again worse than the disease.

The Labour Government has recently announced the Tony Blair Institute's plans to introduce a mandatory Digital ID system in the UK, promoting it as the "solution" to illegal migration. The public reaction has been fascinating: this appears to be one of those rare unifying subjects that both the left and right of the political spectrum oppose, whilst middle-class bureaucrats and technocrats seem to embrace it enthusiastically. At the time of writing, over 2.5 million people have signed a petition against this plan.

The rationale for this scheme is in plain sight within the government's own guidance: it can be revoked at any time:

The system uses state-of-the-art encryption and authentication technology that’s already protecting millions of digital transactions daily. If a phone is lost or stolen, the digital credentials can be immediately revoked and reissued, providing better security than traditional physical documents.

I write this anonymously as a cybersecurity expert, uncertain of the potential repercussions of speaking openly about this topic in the UK. I once looked at countries like Iran and felt grateful that I didn't live somewhere requiring encrypted messaging apps like Signal to communicate safely. Yet here I am, taking similar precautions.

My credentials are substantial: 23 years in the cybersecurity industry, an undergraduate degree in the field, and a professional qualification globally recognised as equivalent to a Master's degree in cybersecurity. My concerns aren't merely technical; they're also behavioural. As security professionals know, people represent the biggest risk to any organisation.

The Immigration Myth

Let's examine the immigration storyline being used to sell these IDs. Illegal migrants crossing the English Channel routinely discard identifying documents at sea. We already have systems to verify work eligibility: valid passports or driving licences, National Insurance numbers (which every UK citizen receives at 16, similar to American Social Security numbers), and criminal background checks through the Disclosure and Barring Service for most positions.

Illegal immigrants aren't applying for legitimate employment. They typically follow two paths: working in the shadow economy through UK contacts, or using black market profiles for food delivery apps created by those with work rights.

I've witnessed this personally; roughly half the time when auditing app orders, the person delivering doesn't match the app profile. They actively avoid video doorbells. Whilst some might dismiss this as harmless, there's a genuine safety concern: companies like Uber Eats, Deliveroo, and Just Eat are sending untracked individuals to homes of vulnerable people and single women.

The Catastrophe Waiting to Happen

The British Government's track record with IT projects and cybersecurity is abysmal. Consider the Post Office Horizon scandal depicted in the Netflix documentary, or Dominic Cummings's revelations about Downing Street running on Windows XP-era technology. Last year alone, both the NHS and Transport for London suffered massive cyber attacks, resulting in convictions under the Computer Misuse Act.

Even Estonia, arguably the world leader in digital governance, has struggled with their national Digital ID system's security. In 2021, hackers accessed photos of over 280,000 Estonian citizens by breaching their Digital ID database.

Consolidating all government ID systems creates a hacker's paradise. Rather than needing to breach multiple distributed systems (passports, driving licences, National Insurance), criminals would have a single target for mass identity theft.

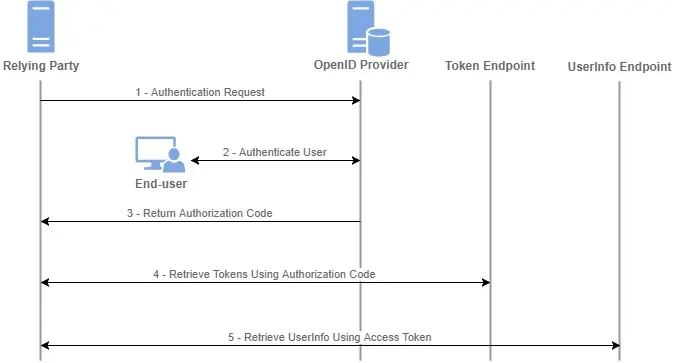

How It Works, Technically

The new UK digital ID system is basically GOV.UK One Login acting as an OpenID Connect (OIDC) Identity Provider. You register your service as a Relying Party, implement the standard Authorization Code + PKCE flow, and get back JWT ID tokens plus a UserInfo endpoint.

Right now, logins are email/password plus SMS/TOTP, but the roadmap is to move to WebAuthn passkeys for phishing-resistant MFA. Services can trigger step-up auth using max_age or by explicitly requesting higher-assurance claims. Everything is built on familiar OIDC plumbing, so your stack doesn’t change much—just handle the JWT validation, claim requests, and session logic.

The One Login mobile app does NFC chip reads from passports, photo capture, liveness detection, and face matching, all scored against the Good Practice Guide (GPG) 45 standard for evidence/validation/verification/fraud. There’s also an in-person Post Office route.

Once proofed, the user’s account can release verified claims (e.g., name, DOB) to your service via OIDC, but only if you’re approved for them. Governance comes from the Digital Identity & Attributes Trust Framework (DIATF), which certifies providers and ensures portability across sectors.

Think “OIDC with optional verified claims,” plan for WebAuthn migration, and design flows that request step-up proofing only when needed.

This might all sound very technical and impressive, but it's far beyond the capabilities of anyone in the Civil Service, let alone elected government.

The Insider Threat

Currently, creating a fraudulent identity requires corrupt insiders at multiple agencies: the Passport Office, HMRC, Disclosure Scotland, and the DVLA. A centralised Digital ID system reduces this to a single insider at one department. The risk multiplies exponentially.

Some might point to other countries with Digital ID systems that haven't reported breaches. In cybersecurity, we have a saying: "There are two types of organisation: those who know they've been hacked, and those who don't know they've been hacked."

When pressed about cybersecurity concerns and the government's history of failed IT projects, Lisa Nandy suggested new legislation punishing hackers would be introduced. We already have the Computer Misuse Act. Hackers, particularly those operating from hostile nations, simply don't care about UK legislation.

Learning from History

Risk assessment in cybersecurity involves examining probability and impact through historical precedent. The most chilling example comes from World War II. The Netherlands had the highest proportion of Jewish citizens sent to concentration camps of any Nazi-occupied nation. Why? They maintained centralised citizen records that the Nazis exploited with devastating efficiency.

Today's government markets Digital ID as a solution to illegal immigration. But what might future governments use this infrastructure for? Once built, such systems rarely disappear; they only expand.

The Social Engineering of a Nation

As cybersecurity professionals, we recognise social engineering as the most common attack vector. The government's approach to selling Digital ID mirrors classic phishing tactics: create urgency around a perceived threat (illegal immigration), offer a simple solution (Digital ID), and discourage scrutiny by labelling critics as opposing national security.

The push for mandatory Digital ID represents a perfect storm of technological overreach, security vulnerabilities, and historical ignorance. It won't solve illegal immigration, but it will create an unprecedented honeypot for criminals and a tool ripe for abuse by future governments.

The 2.5 million signatures on the petition suggest the British public instinctively understands what technocrats seem to miss: some problems can't be solved by throwing technology at them, especially when that technology creates bigger problems than it purports to solve.

As someone who's spent over two decades protecting systems and data, I can say with confidence: this isn't progress; it's a digital nightmare waiting to happen.