The Genocide in Nigeria: 12M Displaced, 185,000 Murdered And 19,000 Churches Gone

Nothing exposes middle-class Marxist racism like an actual tragedy. While students chant death to Israel in support of murderous Islamic rapists, innocent Christians are butchered by the hundred-thousand by Muslim fanatics. Nobody cares. Because it's Africa, and they're poor, rural, and black.

Every thirty-two minutes, a Christian is murdered in Nigeria. Every hour, two more are abducted. Between January and August 2025 alone, jihadist groups slaughtered 7,087 Christians across Africa's most populous nation—an average of thirty-two deaths per day. If this trajectory continues, the year's death toll will surpass 10,000, surpassing even the darkest periods of ISIS's rampage through Iraq and Syria.

Thirty years after the Rwandan genocide, and the Sudanese genocide.

The massacres unfold in near-total silence. Western media outlets devote scant coverage to the crisis. Politicians utter tepid platitudes. International organisations issue carefully worded statements avoiding the word "genocide." The suffering plays out in remote villages with unfamiliar names, far from television cameras and global consciousness. The victims are poor, rural, Black, and Christian—a combination apparently insufficient to command the world's attention.

This is not a sudden eruption of violence. This is a methodical campaign of extermination sixteen years in the making, a slow-motion genocide unfolding across Nigeria's Middle Belt and northern states where jihadist groups have transformed religious persecution into systematic annihilation.

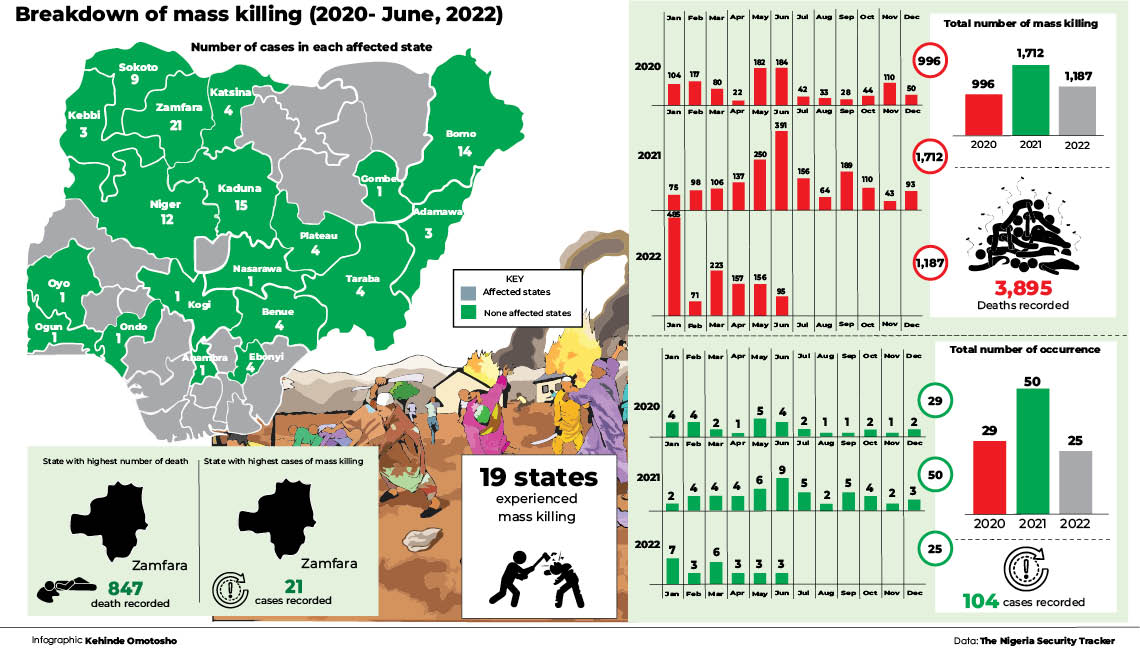

The Numbers Behind the Nightmare

The International Society for Civil Liberties and Rule of Law, known as Intersociety, has meticulously documented the carnage since 2009. Their findings paint a portrait of catastrophic human suffering. Since that year—when Boko Haram's insurgency erupted with the stated aim of establishing an Islamic caliphate across the Sahel—185,000 people have been killed in Nigeria. Of these, 125,000 were Christians. Another 60,000 were Muslims deemed "too liberal" or insufficiently radical by their attackers.

Open Doors, the global Christian persecution monitoring organisation, places Nigeria seventh on its 2025 World Watch List. During their most recent reporting period, from October 2023 through September 2024, they calculated conservatively 3,100 Christians killed and 2,830 abducted. Their assessment is stark: more Christians are killed for their faith in Nigeria than in all other countries in the world combined.

The destruction extends beyond human life. Since 2009, extremists have destroyed, looted, or forced the closure of 19,100 churches—an average of three every single day for sixteen years. Over 1,100 Christian communities have been displaced entirely, their residents driven from ancestral lands they had farmed for generations. More than 600 Christian clergy have been kidnapped, including 250 Catholic priests and 350 Protestant pastors. Dozens were murdered. The Nigerian bishops' conference confirms 145 priests kidnapped in the past decade alone.

Twelve million Christians have been displaced since 2009. Twelve million people forced to flee their homes, their farms, their livelihoods—an internal refugee crisis dwarfing many internationally recognised humanitarian emergencies. In Benue State alone, nearly half a million people have been displaced by violence.

The Yelwata Massacre: A Case Study in Terror

On the night of 13 June 2025, darkness fell on Yelwata, a farming village in Guma County, Benue State. The community, ninety-eight percent Christian, had become a refuge for internally displaced persons fleeing earlier Fulani militia attacks in neighbouring towns. Many families sheltered in compounds around the local Catholic mission, seeking safety in the perceived protection of the Church.

Around ten o'clock that evening, more than forty gunmen descended on motorcycles, riding in pairs. Witnesses reported hearing shouts of "Allahu Akbar" as the attackers opened fire. They moved methodically from house to house, setting homes ablaze and killing indiscriminately. Many victims were locked inside shops and stalls, doused with petrol, and burned alive. Entire families perished. A man, his two wives, and all their children burned beyond recognition. A nine-month-old infant was hacked to death with machetes.

The assault continued for hours. Security forces stationed nearby were quickly overwhelmed. No reinforcements arrived, despite sustained gunfire audible for miles. By morning, Yelwata resembled a warzone. Bodies lay scattered across farmlands. Some burned beyond identification. Others bore the unmistakable marks of machete wounds and close-range gunfire.

Father Remigius Ihyula, Director of the Justice, Peace and Development Foundation in the Catholic Diocese of Makurdi, reported at least 150 confirmed dead initially, with seventy bodies sent to morgues. Hope Faith Ori, a data officer with the diocese, warned the final toll would exceed 200. She was correct. Intersociety's research documented 280 deaths at Yelwata—280 human beings erased in a single night of coordinated violence.

The aftermath brought additional horror. Water sources were contaminated. Food supplies destroyed. Survivors too traumatised and frightened to venture from their hiding places developed diarrhoea and vomiting. "We fear a cholera outbreak," said one resident. "People are dying slowly—not from bullets, but from disease, hunger, and neglect."

Pope Leo XIV condemned the massacre from the Vatican, describing it as a "terrible massacre" and praying for the "rural Christian communities of the Benue State who have been relentless victims of violence." Amnesty International Nigeria called on authorities to "immediately end the almost daily bloodshed in Benue State and bring the actual perpetrators to justice." United States lawmakers urged the Trump administration to redesignate Nigeria as a "country of particular concern" for religious persecution.

The Nigerian government responded with denials and deflections. The federal Information Ministry issued a statement "refuting false claims of religious genocide," insisting terrorists "target all who reject their murderous ideology, regardless of faith." They described the genocide reporting as "false, baseless, despicable and divisive," claiming it "plays into the hands of terrorists and criminals who seek to divide Nigerians along religious or ethnic lines."

Yet the pattern speaks for itself. Yelwata was not an isolated atrocity. Around Easter 2025, militants slaughtered 170 villagers in the neighbouring Ukum and Logo areas of Benue State. Between January and August 2025, Benue State alone accounted for 1,100 Christian deaths. The violence concentrates overwhelmingly in Christian-majority areas, targets churches and clergy specifically, and leaves Muslim communities in the same regions largely untouched.

A Network of Terror

Twenty-two Islamic terror groups now operate with relative impunity across Nigeria, according to Intersociety's research. Several maintain links to the Islamic State and the World Jihad Fund. These are not mere bandits or criminals driven by economic motives. They are ideologically motivated jihadist organisations committed to establishing an Islamic caliphate and eradicating Christian presence from the region.

Boko Haram, whose name roughly translates to "Western education is forbidden," emerged in 2002 in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State in northeastern Nigeria. Founded by Mohammed Yusuf, the group initially focused on promoting a fundamentalist interpretation of Islam. In 2009, following a crackdown by Nigerian security forces, Boko Haram launched a full-scale insurgency. Under Abubakar Shekau's leadership, the group pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in 2015, though a faction later split to form the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP).

Boko Haram's campaign has been extraordinarily brutal. In 2014, the group kidnapped 276 schoolgirls from Chibok, an act that briefly captured global attention. Many remain missing. The group has attacked schools, markets, churches, and mosques that do not conform to their radical ideology. They have beheaded captives, burned villages, and forcibly conscripted children into their ranks.

ISWAP, which split from Boko Haram in 2016, has proven even more tactically sophisticated. The group controls significant territory in northeastern Nigeria and has conducted devastating attacks on military installations. Both organisations specifically target Christian communities, viewing them as legitimate targets in a religious war.

Fulani militants present a more complex challenge. Traditionally, the Fulani people are semi-nomadic pastoralists who herd cattle across West Africa. For generations, Fulani herders and sedentary farming communities coexisted through seasonal arrangements allowing herds to graze on farmland after harvest. Environmental change, population growth, and expanding agriculture have strained these arrangements, creating competition for land and water.

However, characterising the current violence as merely "farmer-herder clashes" obscures the religious and ideological dimensions. Fulani militants increasingly operate as jihadist militias, conducting coordinated attacks on Christian farming communities with military-grade weapons. They burn churches, kill clergy, and force entire villages to flee. Survivors consistently report attackers shouting Islamic slogans and specifically targeting Christians whilst leaving Muslim neighbours unharmed.

James Ortese Iorzua Ayatse, the traditional leader of the Tiv people in Benue State, visited Yelwata a week after the massacre. Walking through the ruins, he stated unequivocally, "What we are dealing with here in Benue is a calculated, well-planned, full-scale genocidal invasion and land-grabbing campaign by herder terrorists and bandits." He dismissed the government's farmer-herder spin as deliberate obfuscation.

The Machinery of Silence

Bill Maher, the American comedian and political commentator, devoted a segment of his HBO programme "Real Time" to Nigeria's Christian persecution in September 2025. Maher, not known for religious advocacy, expressed incredulity at the lack of media coverage. "Nigeria, the fact that this issue has not gotten on people's radar, it's pretty amazing," he said. "If you don't know what's going on in Nigeria, your media sources suck. You are in a bubble."

Van Jones, CNN political commentator, appeared on the programme and called the situation in Nigeria "a crime against African people, black people, and human rights." He noted "almost no response from the global left and no attention from mainstream media" to the slaughter.

Why the silence? The answer lies in the uncomfortable mixture of geography, race, religion, and geopolitics. Nigeria is distant from Western population centres, and its remote farming villages lack the visual drama which captures news editors' attention. The victims are poor, Black, and Christian—demographics which historically struggle to generate sustained international concern compared to conflicts in Europe or the Middle East.

Moreover, addressing the crisis requires acknowledging uncomfortable truths about Islamic extremism in Africa. Many Western media organisations and political figures, legitimately concerned about so-called "Islamophobia," prove reluctant to cover stories framing Muslims as perpetrators of religious violence, even when the evidence is overwhelming. This well-intentioned caution produces perverse outcomes, including the effective erasure of Christian suffering.

Nigerian government denials complicate the picture further: by insisting the violence stems from farmer-herder disputes over resources rather than religious persecution, officials provide cover for international inaction.

If the conflict is merely economic and ethnic, international intervention becomes less justified. Never mind the burned churches, the murdered priests, the villages where every Christian resident was killed or fled.

The Broader Sahel Crisis

Nigeria's Christian persecution forms part of a broader pattern across the Sahel, the semi-arid region stretching from Senegal in the west to Sudan in the east. Islamic extremism has metastasised across this vast territory, exploiting weak governance, porous borders, and historic grievances.

In Burkina Faso, fatalities linked to militant Islamist violence reached 17,775 deaths in the three years following Captain Ibrahim Traoré's 2022 coup—nearly triple the 6,630 deaths in the preceding three years. Christians have been primary targets. More than 200 churches have closed in northern and eastern Burkina Faso due to security threats and actual attacks. Over two million people have been displaced, representing ten percent of the country's population.

The Centre for Strategic and International Studies documented a dramatic escalation: extremist attacks in Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali jumped from 180 incidents in 2017 to over 800 in 2019. Three of the five deadliest attacks in Burkina Faso's history occurred in the past year, including an assault on Barsalogho killing at least 310 people, mostly civilians.

Mali has experienced similar devastation. Since 2020, when the country suffered a military coup, 81 percent of Mali's conflict deaths have occurred—14,384 of the 17,700 people killed since 2000. Extremists have destroyed hundreds of churches and forced entire Christian communities to flee. Missionaries have been kidnapped and killed.

Niger has seen fatalities linked to militant Islamist violence quadruple since President Mahmoud Bazoum's overthrow in 2023, reaching 1,655 deaths. According to ACLED, which tracks conflict victims worldwide, approximately 1,800 people were killed in attacks in Niger since October 2024, with three-quarters of these deaths concentrated in Tillaberi region.

The violence across these nations shares common characteristics: the targeting of churches and Christian ceremonies, attacks timed to religious holidays, the specific singling out of Christian villages whilst bypassing Muslim communities, and the deliberate destruction of Christian symbols and infrastructure.

In some areas, jihadist groups have created "corridors of violence" specifically targeting religious minorities.

Back-to-back military coups since 2020 across Guinea, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger have exacerbated rather than resolved these crises. New military leaders promised to eradicate terrorism but possess poorly equipped militaries and limited intelligence-gathering capacity. Many expelled Western military forces and advisors, creating security vacuums exploited by extremist groups.

How Did We Get Here?

To understand the present crisis requires understanding Nigeria's complex religious and political history. Islam arrived in the region in the eighth century through trade routes connecting the Muslim-majority Maghreb with sub-Saharan West Africa. The Mali Empire recognised Islam as its state religion in the thirteenth century, though Islamic practices often blended with traditional African customs.

Christian missionaries arrived in the nineteenth century. Catholics, sponsored by French colonialists, proved particularly successful. Today, Nigeria's 220 million people divide roughly evenly between Muslims concentrated in the north and Christians predominant in the south, with the Middle Belt representing contested ground where both communities are substantially represented.

British colonial policy cemented these divisions. Lord Lugard, appointed High Commissioner of British Northern Nigeria in 1900, opted to rule through existing Islamic governance structures—the Sokoto emirs—to avoid conflict.

This preserved the Islamic character of northern Nigeria whilst southern Nigeria remained under direct British rule. The "forced union of marriage" Lugard envisioned when granting Nigeria independence as a single entity in 1960 embedded structural religious tensions into the nation's foundation.

Post-independence politics became dominated by northern Islam. In 1986, Nigeria joined the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (then the Organisation of the Islamic Conference). In 1999, Zamfara State Governor Ahmad Sani Yerima announced the implementation of sharia.

By 2000, eleven other northern states had adopted sharia, including punishments such as flogging, amputation, and execution for blasphemy. Whilst theoretically applying only to Muslims, Christian minorities often felt compelled to comply.

Boko Haram emerged when the group's founder, Mohammed Yusuf, preached against Western education and secular governance, advocating strict sharia implementation. When Nigerian security forces killed Yusuf in 2009, the group launched its insurgency under Abubakar Shekau, who proved far more violent and uncompromising.

The 2011 collapse of Libya's government proved catastrophic for the Sahel. Muammar Gaddafi's arsenal—anti-aircraft weapons, rocket-propelled grenades, assault rifles—flooded into the hands of insurgent groups. The region's fragile states proved unable to contain the sudden influx of sophisticated weaponry. Extremist groups proliferated, exploiting political vacuums and ethnic grievances.

Living Under the Shadow of Death

What does daily life look like for Christians in Nigeria's persecution zones? Imagine waking each morning uncertain whether you will survive to evening. Imagine sending your children to school knowing armed militants could attack at any moment. Imagine farming the land your family has cultivated for generations whilst watching the horizon for motorcycle-borne raiders. Imagine attending Sunday worship service aware your church could be the next burned to ashes, your congregation the next massacred.

Father Mathew Eya, a Catholic priest serving St Charles Parish in Eha-Ndiagu, Enugu State, was killed on 19 September 2025. Attackers riding motorcycles intercepted his vehicle near a hospital construction site, first shooting the tyres to stop the car, then killing Father Eya at close range in what appeared to be an execution-style murder.

He joins the 145 Nigerian priests kidnapped over the past decade, many of whom were killed despite ransom payments.

Father Wilfred Ezeamba, serving St Paul Parish in Agaliga-Efabo, Kogi State, was kidnapped on 12 September 2025. After several days in captivity, his captors released him on 16 September. Father Ezeamba was one of the fortunate ones. Many kidnap victims never return.

The economics of kidnapping have become staggering. SBM Intelligence, an Africa-focused research firm, documented in their August 2024 report hostage-takers demanding thirty-two million dollars in ransom for 7,568 people abducted between July 2023 and June 2024.

Bishop Mathew Hassan Kukah of Sokoto described kidnapping as "a criminal industrial complex" generating millions in revenue. Emeka Umeagbalasi of Intersociety estimates 250 Catholic priests have been kidnapped since 2015, alongside at least 350 clergy from other denominations.

For those who survive attacks, life becomes a struggle for basic survival.

Refugees crowd into camps where food, healthcare, and clean water remain scarce. Children develop diseases from contaminated water and inadequate sanitation. Families sleep in makeshift shelters, vulnerable to the elements and further attacks. Women face sexual violence. Men cannot work their fields, leaving families dependent on inadequate humanitarian aid.

Schools close. Markets empty. Entire communities disappear. The social fabric tears apart as families flee in different directions, losing contact with relatives. Children grow up traumatised, having witnessed murders, seen their homes burned, watched their parents killed. The psychological damage compounds the physical destruction.

Too Little, Too Late

In December 2020, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, serving in President Trump's first administration, designated Nigeria as a "Country of Particular Concern" (CPC) for "systematic, ongoing, egregious religious freedom violations." This designation triggers potential sanctions and conditions American aid on demonstrable progress protecting religious freedom.

On 17 November 2021, however, the Biden administration inexplicably removed Nigeria from the CPC list during a visit to Abuja. Secretary of State Antony Blinken acknowledged prevailing violence but cited "progress" in Nigerian government efforts, including military operations against jihadists and interfaith dialogues. Human rights advocates condemned the decision as catastrophic. Open Doors called it "a devastating blow," noting Christian killings had surged in 2021.

The removal emboldened Nigerian authorities to dismiss international criticism. Violence escalated. The death toll climbed. Churches continued burning. The "progress" Secretary Blinken cited proved illusory.

In September 2025, Republican Senator Ted Cruz introduced the Nigeria Religious Freedom Accountability Act, designed to hold officials who "facilitate Islamic Jihadist violence and the imposition of blasphemy laws" accountable. The bill seeks to redesignate Nigeria as a CPC and designate Boko Haram and ISWAP as "entities of particular concern." Representative Riley Moore wrote to Secretary of State Marco Rubio urging similar action.

The Trump administration has issued statements condemning the violence. A White House statement affirmed, "The Trump administration condemns in the strongest terms this horrific violence against Christians," stressing religious freedom represents "a moral imperative and a fundamental pillar of American foreign policy."

Yet statements alone prove insufficient. Without concrete action—sanctions, conditioned aid, diplomatic pressure—words ring hollow.

The European Union and United Nations have issued reports and resolutions but taken little substantive action. International humanitarian organisations struggle to operate in dangerous conflict zones with inadequate funding and security.

The African Union remains largely silent, unwilling to criticise a member state or confront the uncomfortable reality of religiously motivated violence across the continent.

Why This Should Matter to Everyone

Religious persecution in Nigeria carries implications far beyond the immediate victims. The erosion of religious pluralism and minority rights anywhere threatens these principles everywhere. When the international community ignores genocide based on the victims' geography, race, or religion, we establish precedents that will haunt future crises.

Failure to confront Islamic extremism in the Sahel allows these movements to consolidate territory, refine tactics, and inspire affiliates elsewhere.

The Islamic State's stated ambition is Islamising the entire African continent. Nigeria, with Africa's largest population and significant Christian communities, represents a crucial battlefield. Losing Nigeria would embolden extremists across the region.

The displacement of twelve million Nigerian Christians creates humanitarian catastrophes requiring international response. Refugee flows destabilise neighbouring countries and create conditions for further conflict.

The economic devastation compounds poverty and creates environments where extremism recruits desperate young men.

There are also moral dimensions transcending geopolitical calculations. These are human beings—mothers, fathers, children—being systematically murdered for their religious faith. They pray in churches not unlike those found in London, Lagos, and Los Angeles. They sing hymns familiar to Christians worldwide. They baptise their children, celebrate Christmas, observe Easter.

Then armed men arrive in the night and slaughter them.

The silence surrounding their suffering indicts our collective moral conscience. We claim to oppose genocide, yet ignore this one. We profess concern for human rights, yet allow these violations to continue. We condemn religious persecution, yet avert our eyes when the victims are African Christians and the perpetrators Islamic extremists.

Glimmers of Hope Amidst the Darkness

Despite unimaginable persecution, Nigeria's Christians refuse to abandon their faith. Church attendance remains strong. Auxiliary Bishop Ernest Obodo of Enugu conferred confirmation on 983 people in June 2025 at Holy Spirit Cathedral. Even as attacks intensify, believers gather for worship, knowing each service could be their last.

Father Dominic Asor, rector of St James Minor Seminary, told his students, "We must not flee from our vocation because of trials, insecurity or the lure of worldly comfort. God who called us will sustain us, but we must remain faithful and focused."

The persecution paradoxically strengthens faith for many survivors.

"What's remarkable is how persecution has actually strengthened the church in many ways," said one observer. "We're seeing unprecedented unity across denominations as believers support each other through displacement and loss. In Burkina Faso, Christians from different traditions are praying together and sharing resources in ways we've never seen before."

Some 400,000 believers continue witnessing to their faith even in North Korea, ranked number one on Open Doors' World Watch List. As one secret fieldworker stated, "Despite persecution, nothing and no one can stop the church from growing."

Open Doors' Arise Africa campaign focuses resources on supporting persecuted Christians across sub-Saharan Africa. International Christian Concern documents attacks and advocates for policy changes. Genocide Watch monitors the situation and presses for international intervention.

Individual acts of courage inspire hope. Pastors who refuse to flee their congregations despite death threats. Lay leaders who shelter displaced families in their homes. Women who care for orphans whose parents were murdered. Young people who choose theological education even knowing clergy are prime targets.

The question remains whether the international community will finally act before Nigeria's Christian population faces the same fate as Christians in ancient Anatolia or North Africa—once-thriving communities erased by centuries of persecution until only archaeological ruins remained as testament to their existence.

What Must Be Done

Ending Nigeria's Christian genocide requires coordinated international action addressing both immediate violence and underlying conditions enabling extremism.

- First, the United States must redesignate Nigeria as a Country of Particular Concern and condition aid on demonstrable progress protecting religious minorities. American military assistance, intelligence sharing, and development aid should depend on verifiable improvements in religious freedom and prosecution of perpetrators. The Trump administration's statements require backing with concrete policy.

- Second, the European Union should impose targeted sanctions on Nigerian officials who facilitate violence or obstruct justice. Travel bans and asset freezes concentrate minds. Those enabling genocide must face personal consequences.

- Third, the United Nations Security Council should authorise an armed peacekeeping mission focused on protecting vulnerable communities in Nigeria's Middle Belt and northeastern states with permission to use force if necessary. Nigerian security forces have proven unable or unwilling to prevent massacres. International troops could establish protected zones allowing displaced persons to return home safely.

- Fourth, international criminal proceedings must target extremist leaders. The International Criminal Court should investigate Boko Haram, ISWAP, and Fulani militia leaders for crimes against humanity and genocide. Justice proceedings, even if perpetrators remain at large, establish accountability and signal the international community's refusal to tolerate such atrocities.

- Fifth, Western nations should significantly increase humanitarian aid to displaced Christians. The twelve million internally displaced persons require food, shelter, healthcare, and education. International aid organisations need funding to operate effectively in dangerous environments.

- Sixth, media organisations must cover Nigeria's Christian persecution with the same intensity devoted to other humanitarian crises. Sustained coverage creates political pressure for action. Journalists should travel to affected areas, interview survivors, document evidence, and refuse to accept government denials contradicted by overwhelming evidence.

- Seventh, Christian churches and organisations worldwide must mobilise their congregations. Prayer, whilst spiritually important, must accompany advocacy, financial support, and political pressure. Church leaders should meet with government officials, write opinion pieces, and refuse to let this crisis fade from attention.

- Eighth, educational institutions should incorporate Nigeria's Christian persecution into curricula addressing human rights, religious freedom, and genocide prevention. Future generations must learn these lessons so such horrors never repeat.

- Ninth, technology companies should monitor and remove extremist content inciting violence against Christians. Social media platforms enable jihadist recruitment and coordination. Tech firms possess tools to disrupt these networks but must deploy them aggressively.

Finally, Nigerian authorities must acknowledge the religious dimensions of violence, prosecute perpetrators vigorously, and protect vulnerable communities. Without genuine government commitment, external interventions prove insufficient. Nigerian political leaders must choose: will they defend all their citizens regardless of faith, or acquiesce whilst one-third of their population faces extermination?

A Moral Test We Are Failing

Every genocide begins with violence the world ignores. Small atrocities escalate into systematic slaughter because international intervention arrives too late. We possess detailed documentation of unfolding catastrophe. Survivors testify. Bodies pile up. Churches burn. Yet we collectively choose inaction.

History will judge our response to Nigeria's Christian persecution. Future generations will read about 7,087 Christians slaughtered in seven months and wonder why the international community stood idle. They will view photographs of burned villages and charred corpses and question how such horrors unfolded whilst the world watched.

We cannot claim ignorance. Intersociety's meticulous research provides documented evidence. Media reports detail specific attacks. Survivors bear witness. The information exists for anyone willing to look.

We cannot claim this is merely a "farmer-herder dispute" when attackers shout Islamic slogans whilst burning churches and specifically targeting Christian clergy. The pattern reveals systematic religious persecution meeting every definition of genocide.

We cannot claim Nigeria is too distant or complex to address. International interventions have deployed to locations far more remote for crises far less severe. Political will, not geographic proximity, determines response.

The uncomfortable truth is we are failing a fundamental moral test. A generation of Nigerian Christians is being systematically murdered whilst we concern ourselves with less consequential matters. Their blood stains our collective conscience. Their suffering demands response. Their voices cry out for justice.

Thirty-two Christians will die in Nigeria today. Thirty-two tomorrow. Thirty-two the day after. Week after week, month after month, year after year until either the killing stops or Nigeria's Christian population ceases to exist.

The choice is ours. We can continue averting our eyes, dismissing reports, accepting government denials, and allowing the machinery of genocide to grind onward. Or we can act—demanding accountability, supporting survivors, pressuring governments, and refusing to remain silent whilst our brothers and sisters in Christ are slaughtered.

Emeka Umeagbalasi warns, "If the trend continues, Christianity could be wiped out from Nigeria by 2075." Fifty years represents merely a generation—a blink in historical time. Ancient Christian communities across North Africa and the Middle East disappeared this way: gradual persecution, international indifference, eventual extinction. The Coptic Christians of Egypt, once the overwhelming majority, now survive as a persecuted minority. The Christians of Turkey, once Byzantium's heartland, number in the tens of thousands in a nation of eighty-five million.

Nigeria's Christians face this same trajectory unless the world intervenes. Their churches will crumble into archaeological ruins. Their villages will be emptied and occupied by others. Their culture, traditions, and faith will survive only in diaspora communities scattered across the globe. Future scholars will study their disappearance and wonder why no one acted.

We still have time. The window closes with each passing day, each new massacre, each burned church. But time remains to alter this trajectory, to say "never again" and mean it, to demonstrate through action rather than rhetoric our commitment to human dignity and religious freedom.

This isn't an abstract problem. It is an ISLAM problem.

The question before us is simple: Will we act? Or will we stand idle whilst a people are erased?