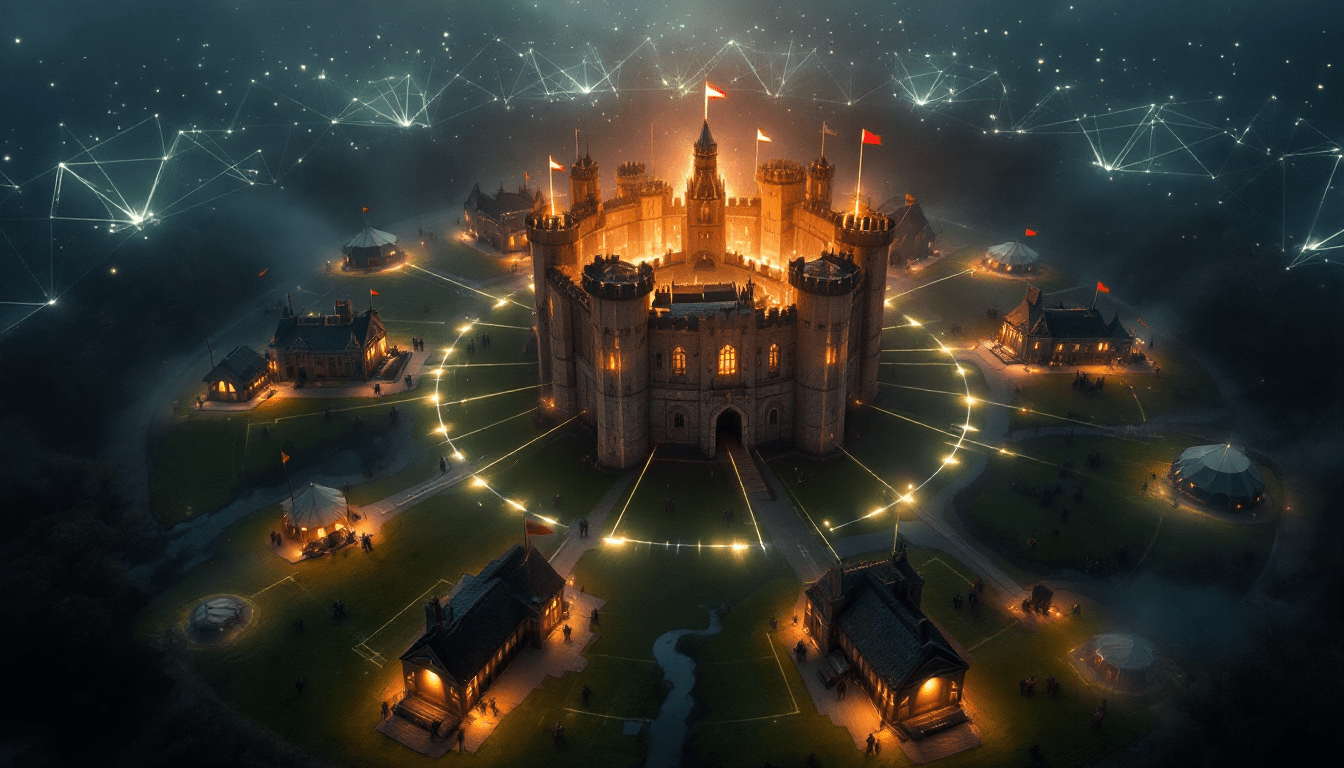

The Implosive Cartel: Organising The Right's Byzantine Generals

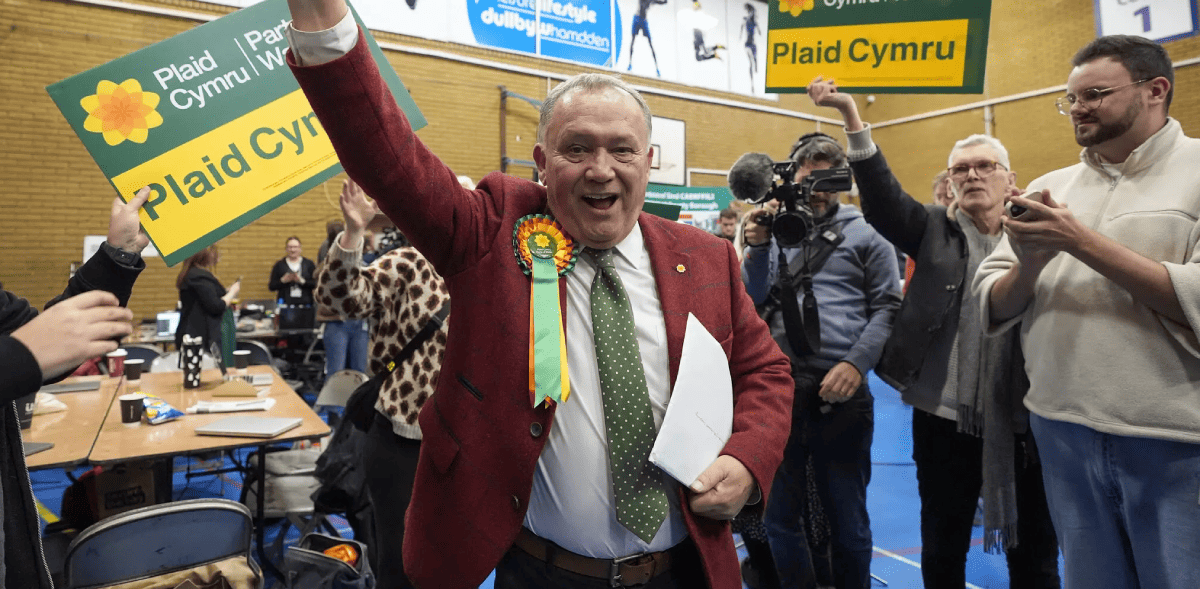

Fragmented political parties can be transformed into individual "laboratories of democracy" which target specific electoral niche voting blocs, then fuse together as a cartel to overcome the FPTP system using implosion weapon mechanics. Electoral mad science only seems mad until... it works.