The Judicial Roadblock to Free Speech In The UK

Britain's proposed First Amendment-style Free Speech Act risks empowering unaccountable judges due to the UK's opaque judicial selection process, unlike the US system where judges face democratic accountability through presidential appointment and Senate confirmation.

Free speech has been effectively abolished in Britain. Many solutions to restore free speech are being proposed, most of which rely on implementing an equivalent of the US First Amendment for Britain. Is this possible? What are the risks involved with limiting parliamentary supremacy and establishing natural rights? Can the judiciary be controlled and held accountable?

Why The Need For A UK Free Speech Act?

In recent years, the total collapse of free speech in Britain has become ever more obvious. People have been arrested for praying in public areas because they are too close to abortion clinics, more than 12,000 people a year are arrested for speech offences, the police record people for conducting legal speech with non-crime-hate-incidents (NCHIs), and just within the last week the government's implementation of the Online Safety Act requires people to provide their personal identification to use basic internet functions which we are told is to protect children from harmful content.

One example of the regime’s deeply oppressive attitude regarding freedom of speech for regular British folk was clearly shown by their arrest and sentencing of Lucy Connolly, who is currently serving a longer jail sentence than many convicted paedophiles in this country, for posting (and then swiftly deleting) comments that would not have passed the imminent lawless action test in the US (after the massacre of three white girls at a Taylor Swift dance class).

Most of this oppression is likely due to the fear of losing control of the unstable situation that they have imposed on the nation with unwanted and uncontrolled mass migration; many of which are from incompatible cultures that are hostile to Western culture and the British people. This has led to many calling for Britain to create its own version of the American First Amendment.

Proposals, First Amendment, and Problems

Many proposals are incoming in the attempt to secure freedom of speech and prevent the current situation from ever arising again. Almost all of them are taking inspiration from the US First Amendment, using the framing of natural rights which are inalienable and universal amongst the human species, and therefore beyond the grasp of parliamentary authority.

There can be a level of naivety amongst commentators today when discussing this topic, and perhaps a misguided belief in the ease of transferability of the American method in securing free speech. What is preventing a universalist “Free Speech Act” from evolving into another Human Rights Act (HRA)? Who will be interpreting the Act if it is beyond the remit of Parliament to alter?

Who is selecting those who are endowed with the immense ability to interpret and apply this Act which is beyond the ability of those in Parliament? Are those who choose these judicial titans able to be held to account? Are those who are appointed to this judicial caste able to be held to account? Are there any democratic pressures facing this new judicial caste and those who appoint them?

US Judicial Process and Balance of Power

These are important questions that many tend to overlook when considering the ‘globalisation’ of the US First Amendment. The American system is carefully calibrated to effectively deal with many of these issues, especially regarding judicial selection and judicial accountability.

In the US, all federal judges are directly appointed by the President and then confirmed by the Senate, according to Article III of the Constitution. State judges are selected either by election or appointment, and the methods vary state by state, according to each state’s constitution. Elections are run as either: partisan (party-affiliated), nonpartisan (non party-affiliated), or as retention (whether the incumbent is allowed to continue). Appointments are typically made by an executive, such as the elected Governor of the state, and then confirmed by the state legislature.

The nominating process for appointments can have “merit-based” and “independent” commissions (which typically include the executive in charge of making the appointment) for the construction of a shortlist of nominated candidates from which the executive then selects his appointee before the confirmation process with the state legislature.

Notice how nearly all aspects of the selection process directly involve people that have been elected by the public and are accountable to the public for reelection. The power of the judicial branch is checked by the powers of the executive branch and the legislative branch, through the selection process. This process for judicial selection is far more transparent and democratically legitimate than the processes in Britain for judicial selection.

UK Insanity: Unaccountability and Opaqueness

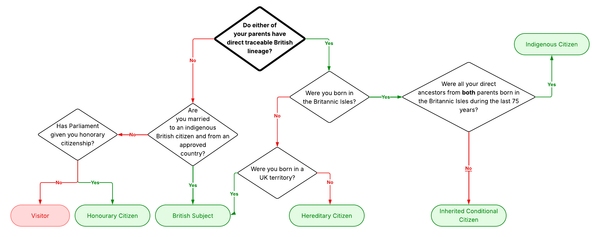

In the UK, judicial selection is conducted through “independent” bodies that have “merit-based” processes, with the Judicial Appointments Commission (JAC) being the commission that selects candidates for judicial office in courts and tribunals in England and Wales.

The Supreme Court selects its judges through its own Supreme Court selection commission which is formed with five members: President of the Supreme Court, a senior (non-Supreme Court) judge, and three representatives (one of which cannot be a lawyer) from each of the judicial appointment committees (JAC, Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland, and the Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Commission) across the UK. The UK Supreme Court (UKSC) describes the key (simplified) nine step selection process as follows:

- The Lord Chancellor convenes an independent selection commission whose membership is described above.

- The vacancy is advertised. Applications are sought from a wide range of candidates, including those who are not currently full-time judges, and those who will increase the diversity of the UKSC. Applicants are invited to submit a personal statement, examples of their previous work, and details of independent assessors.

- The Lord Chancellor, the First Minister in Scotland, the First Minister for Wales, the Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Commission, and senior judges across the UK are consulted as part of the selection process.

- Applicants are shortlisted based on merit and then interviewed by the selection commission.

- The selection commission submits a report to the Lord Chancellor stating who has been selected to fill the vacancy.

- On receiving the report, the Lord Chancellor is required to consult the First Minister in Scotland, the First Minister for Wales, the Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Commission and senior judges.

- When a person has been selected under the selection process, the Lord Chancellor has three options. They may accept the selection commission's selection, reject it, or require the selection commission to reconsider. The Lord Chancellor can only reject the selection or require the selection commission to reconsider in certain circumstances.

- If the selection commission's selection is accepted, the Lord Chancellor notifies the Prime Minister of the name of the successful applicant who, in turn, notifies HM The King who makes the formal appointment.

- The Prime Minister's Office announces the appointment.

This process is so absurdly opaque and vague, there is not one person who could possibly take responsibility for a bad appointment. There is no way to assign blame or democratic accountability. Is the Lord Chancellor to blame for her “independent” selection commission's choice? Are the “independent” assessors to blame for their assessments, in Step 2? Are the devolved representatives to blame for their, likely very minor, input along with the vaguely described consultation with senior UK judges?

Who is even in charge of the shortlisting process based on merit in Step 4, before being interviewed by the selection commission? Are they responsible and to be held to account? Maybe it is the selection commission for their report to the Lord Chancellor who deserves to be held to account? Perhaps the Lord Chancellor’s further consultation with devolved representatives and senior judges is the key aspect? Is the Lord Chancellor to blame for not rejecting the selection by the commission in Step 7, even though the rejection can only occur in certain (undescribed and likely purposefully vague) circumstances?

The process is (almost certainly) purposefully opaque and unintelligible, such that no one can actually be held to account or responsible for any decision that is made. Unfortunately, the selection process for JAC seems equally or more opaque than for the UK Supreme Court.

The JAC describes themselves as:

The Judicial Appointments Commission selects candidates for judicial office in England and Wales, and for some tribunals with UK-wide powers.

and that:

It is our statutory duty to select candidates on merit, who are of good character. We believe in a judiciary that reflects the diverse society it serves and we have a statutory duty to attract diverse applicants from a wide field.

According to the Courts and Tribunal Judiciary,

The [JAC] Commission was set up on 3 April 2006 – under the terms of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 – in order to maintain and strengthen judicial independence by taking responsibility for selecting candidates for judicial office out of the hands of the Lord Chancellor and making the appointments process clearer and more accountable.

It is extremely opaque as a non-judge to see what JAC means when they refer to “merit”. There is abundant guidance on how JAC defines and measures “good character.” There is much material referring to their DEI measures. Not much available on merit. How is JAC defining and measuring merit? How are those who selected the judges held to account by members of the public? How is the JAC held to account for its decisions? Are there internal processes? Does being “independent” simply mean being independent from responsibility and accountability? What responsibility does the Lord Chancellor now have (since 2006) and what, effectively, is their precise role in judicial selection?

Compare this absurd process to the way federal judges (including for the Supreme Court) are selected in the US. The President makes his selection, then the appointee goes before the Senate to be confirmed, which is a public hearing for all to see. The US process is transparent, simple, intelligible, and those involved in the selection process are able to be held to account through the democratic process.

Why Does This Matter?

So what! Who cares that England, and Britain more generally, has an opaque and largely unaccountable judicial selection process? Why does this matter for the Free Speech Act? Why can’t Britain just have what the US has?

The UK judiciary and their selection process, being largely unaccountable, poses a huge problem for establishing a functioning free speech ecosystem through limiting Parliamentary supremacy and enacting a universalist, deeply entrenched, Free Speech Act. Given this unaccountability and opaqueness, any such deeply entrenched Act would empower and embolden an unaccountable caste of judges, who would then be able to interpret and apply this Act according to their own wishes with limited-to-zero ability to be held accountable, similar to the HRA and its consequences.

With parliamentary supremacy, (inevitable) undesired legal precedents that are set by judicial rulings would be able to be dealt with by parliament amending the Act and/or dismissing the judicial activists. This becomes extremely difficult with deep entrenchment limiting parliamentary power.

The problem is not only that the British judicial selection process is opaque and unaccountable, but also that the academic and judicial culture is much more uniform in Britain than it is in the US. In the US, there are several schools of thought regarding constitutional law: originalism, textualism, and living constitutionalism. There are thriving associations of both “right wing” legal professionals and “left wing” legal professionals.

This is an important feature of the American legal and judicial ecosystem. It allows elected officials to appoint judges that agree with their supporters' interpretation of constitutional legal doctrine. This is critical to the functioning of the US. For example, if there had been a “bad” legal decision that many believed to be an unconstitutional legal ruling, then the public could vote for specific officials to select for judges (many of whom are known public figures and to which school of thought they subscribe to), who would be able to advocate for their interpretation. This makes the US judiciary far more responsive to the electorate over the medium and long run, than the British judiciary.

The lack of diversity of thought amongst the judicial and legal profession in Britain, in combination with the unaccountable and opaque judicial selection process, guarantees significant hurdles that impede any easy transition toward an American First Amendment situation. These issues are prerequisites to solve prior to having a functioning Free Speech Act which limits parliamentary sovereignty.

If these issues are not dealt with, namely: unaccountable judiciary, faulty training of UK legal professionals, lack of diverse schools of legal thought that are able to counter critical legal theory and one-sided judicial activism, and the democratic deficit in judicial selection, then there is a significant chance that the Free Speech Act ends up with Free Speech Tribunals, similar to the HRA with the currently deranged Immigration Tribunals.

Other US Considerations For Securing Free Speech

None of this mentions that the US has 50 semi-autonomous states that are evenly divided along political lines, 100+ years of important legal precedents, or the Second Amendment, all of which are important to the free speech landscape in modern America.

Globalising the First Amendment is very difficult and comes with a cost in the British system. Limiting parliamentary supremacy for speech will likely immediately lead to calls that parliamentary supremacy be further limited according to other universalist “natural rights.” Will this universalism impair a future government’s ability to enact mass deportations or redefine citizenship or limit the spread of certain foreign religions?

If Britain decides to implement a First Amendment equivalent (with entrenchment), then it must be accompanied by a total transformation of the judicial selection process which emphasises transparency, simplicity, accountability, democratic input, and intellectual diversity, in order to foster a viable free speech landscape in Britain.