The Self-Defence Act: Recovering the English Right to Bear Arms

The bearing of arms has always formed a shared civic stewardship duty in England where the citizen is a lawful auxiliary to peacekeeping. Women, and those in rural/under-policed areas deserve the capacity to protect themselves. ESDA establishes the Defence Firearm Certificate to restore this trust.

In the past year, two attempts were made on the life of President Donald Trump and one on the life of Charlie Kirk – a father, entrepreneur, and conservative commentator – who was brutally assassinated on 10 September 2025. These tragedies, like countless others, ignited a familiar pattern: moral panic followed by policy paralysis. American gun control becomes a flashpoint, a talismanic object in the culture war, when what it requires is neither mythologising nor moralising – but precision.

When violence makes headlines, the impulse is to "do something" fast and ask the constitutional questions later. Yet haste is the enemy of governance. If we are to reckon honestly with the problem of violence – whether in America or Britain – we must first resist the reductive slogan, the tidy storyline. The devil, as ever, lies in the detail.

When American gun-control comes under scrutiny, as it routinely and wearily does, there is something unpalatable about Britain’s eagerness to join in, sign petitions, waft signs, and rail against the political goings-on of a sovereign nation whose very foundational principles were laid out to escape our control. Doubtless, American citizens enjoy our input on gun-control as much as we enjoyed Barack Obama’s comments the British would be at the “back of the queue” should they dare to leave the E.U. back in 2016. Accordingly, let us proceed with more caution than the 44th president offered.

Kirk understood Restorationism, and the need to return to Anglo-British exceptionalism. In his Oxford Union speech, he explains, to "Make America Great Again" is to return America to its Anglo-British roots. He was right.

The English Bill of Rights of 1689 forms the basis of America's arrangement, and that includes the right to arms.

The Foundations of the Right to Bear Arms

The concept of an armed citizenry in English law predates the existence of both modern firearms and the American republic. Its roots lie deep in the medieval and early modern legal and military structures of the English kingdom. Central to this tradition is the Assize of Arms of 1181, issued by King Henry II, which required every free man to possess arms appropriate to his station and to be ready to defend the realm when called upon. This was not a military duty in the modern sense but a civic one – an expectation individuals would contribute directly to public defence.

The 1181 Assize mandated that each man should have armour and weapons suited to his wealth and social status. This not only entrenched the notion of a citizen-soldier but linked liberty to the right and responsibility of bearing arms. The tradition continued through the Statute of Winchester in 1285, which reaffirmed this expectation and introduced mechanisms for regular inspection of weapons by local constables.

During the Tudor and early Stuart periods, the role of the militia expanded as a bulwark against internal disorder and external threat. Citizens were trained periodically and called out for musters, forming a decentralised but regulated defence force. The concept culminated in the English Civil War, where the contest between Parliament and the Crown often centred on who had the authority to command the militia – and by extension, who controlled the people’s arms.

The Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the subsequent Bill of Rights 1689 enshrined the Article VII right of Protestants to bear arms for their defence, “suitable to their conditions and as allowed by law.”

That the subjects which are Protestants may have arms for their defence suitable to their conditions and as allowed by law;

Although qualified, this was the first statutory recognition of an individual right to arms grounded in political liberty and religious autonomy. The clause was a direct response to the perceived tyranny of James II, who had disarmed Protestants while maintaining a standing army. The Bill of Rights, therefore, was both a political and military settlement, confirming a citizenry with arms was a safeguard against absolutism.

These principles were transmitted to the American colonies, where frontier life and resistance to British interference further entrdutyenched the idea of arms-bearing as a civic virtue and a natural right. Colonial statutes mirrored the English laws, requiring able-bodied men to keep muskets, powder, and shot. By the time of the American Revolution, the right to bear arms was no longer just a defensive measure – it was a philosophical assertion of sovereignty.

The American Second Amendment thus emerges not in isolation but as the logical evolution of a centuries-long Anglo legal tradition.

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

Its text, affirming the necessity of a “well regulated Militia” and the right of the people to keep and bear arms, encapsulates this inherited belief liberty and defence are coequal pillars of a free society.

Unlike Britain’s parliamentary sovereignty, which permits erosion of rights by statute, the United States embeds the right to keep and bear arms in its constitutional fabric. That right, affirmed in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) and extended to state action in McDonald v. Chicago (2010), protects the individual’s right to own firearms for lawful purposes, chiefly self-defence.

Justice Scalia, in Heller, rejected the idea the Second Amendment merely protected militia service, asserting it as “an individual right, having nothing to do with service in a militia.” Justice Alito clarified the amendment arose in response to “King George III’s attempts to disarm the colonists in the 1760s and 1770s,” invoking the colonists’ “rights as Englishmen to keep and bear arms.”

The American right to bear arms may seem alien today to modern Englishmen – who, ironically, agree more with George III’s disarming tendencies. And yet, it was Britain that exported this right to both America and Australia.

The roots of this right lie in Henry II’s Assize of Arms of 1181, a law of an unarmed era, which nonetheless established that every free man must arm himself according to his rank for the defence of the realm. The tradition persisted through medieval mustering systems, Tudor statutes, and common law recognitions, right up until the Glorious Revolution codified it as a Protestant safeguard against absolutism.

This legacy informed colonial law. In early America, militias were a civic obligation – every able-bodied male was expected to be armed and capable. This was not frontier mythos, but civic order. The American Revolution, and later the Constitution, preserved this English tradition and adapted it to a republic.

A History of Curtailment in the United Kingdom

The history of firearms regulation in Britain is not a sudden rupture but a long arc of steady erosion. What was once a civic expectation—armed self-sufficiency rooted in the common law—has gradually become a bureaucratic privilege, granted by the state under increasingly narrow terms.

This transformation did not occur overnight. It followed a path that wound through wars, uprisings, class fear, imperial collapse, and moral panic. Understanding this process is crucial to understanding how Britain became one of the most heavily disarmed populations in the Western world.

From Militia Duty to Political Control

The legal tradition of bearing arms in England begins not with firearms, but with feudal and civic duty. The Assize of Arms of 1181, issued by King Henry II, required every freeman to possess weapons appropriate to his wealth and social class. This was a defensive measure against rebellion and foreign incursion. The Statute of Winchester (1285) reaffirmed these obligations, ordering regular inspection of arms and mandating that citizens pursue wrongdoers in hue and cry.

These laws were not about state monopolisation of violence. On the contrary, they decentralised it, embedding it in the household and the parish. This tradition lasted through the Tudor period, where “trayned bandes” were formed—semi-regular militias drawn from the population. Even the unpopular Stuart monarchs did not question the general right to arms—only the political threat posed by them.

The Militia Act of 1661, however, passed under Charles II following the Restoration, marked a significant curtailment. It asserted royal control over the militia, which had previously been under parliamentary command during the Civil War. It was a veiled disarmament of political opponents, namely Puritan and republican elements who had supported Cromwell. From this point onward, arms ownership began to divide along political lines.

The Bill of Rights 1689: A Conditional Right

The English Bill of Rights followed the Glorious Revolution and affirmed the right of “Protestants to have arms for their defence suitable to their condition and as allowed by law.” While it is often cited as foundational to Anglo-American firearm liberties, its language was intentionally qualified.

It did not confer a universal right, but recognised the legitimacy of self-defence and the illegitimacy of disarmament without due process. It was a safeguard against absolutist monarchs—specifically James II, who had attempted to disarm Protestants while arming a standing Catholic army.

It is worth noting that Catholics were effectively excluded from this right. Under the Penal Laws, Catholics were banned from possessing arms—a restriction codified under the Disarming Act of 1695 (Ireland) and mirrored in Scotland.

The Disarmament of Scotland

Perhaps the most explicit group disarmament in British history occurred after the Jacobite Risings. In response to the 1715 rebellion and more devastatingly after the defeat at Culloden in 1746, Parliament passed a series of acts targeting the Highland clans, many of whom had supported the Stuart cause.

The Disarming Act of 1716, and more comprehensively, the Act of Proscription of 1746, made it a criminal offence for Highlanders to possess broadswords, dirks, pistols, and other traditional arms. Enforcement was brutal and widespread. The goal was not merely to prevent violence but to dismantle clan culture and authority. This was the beginning of what scholars have called the “internal colonisation” of the Highlands, with arms disarmament as its keystone.

This distinction is critical. The English tradition had allowed for armed self-defence; but in Scotland and Ireland, arms were often seen as a mark of disloyalty or rebellion. Thus, the very geography of Britain came to reflect different policies: the further from London, the tighter the grip.

Victorian Laws: Light Touch, Growing Normalisation

For much of the 18th and early 19th centuries, firearms ownership was largely unregulated for the English middle and upper classes. Gentlemen were expected to own sporting arms. Farmers possessed shotguns. There was no comprehensive framework for licensing or oversight.

This began to change in the Victorian era. The Gun Licence Act of 1870 was ostensibly a tax—a revenue mechanism rather than a public safety law. But it had a profound cultural effect. It introduced the idea carrying or using a gun in public required state approval. While the fee was modest and compliance partial, the act signalled a shift: gun ownership was no longer presumed—it was now to be administered.

Early 20th Century: Fear of the Returning Soldier

The first major public safety-oriented firearms law was the Pistols Act of 1903. It imposed age restrictions on pistol purchases, required sales records to be kept, and created a framework for dealers. This was modest by today’s standards but significant in its intent. The concern was urban crime and political unrest, especially following anarchist violence in Europe.

The watershed moment came in 1920.

After World War I, the British state faced returning veterans, economic hardship, labour unrest, and fears of Bolshevik revolution. The Firearms Act 1920 was passed in this climate. It required a police-issued certificate to purchase or possess firearms other than shotguns.

Initially, self-defence was listed as a legitimate reason. But police forces soon narrowed this, preferring hunting or sport as justifications. The law marked a new philosophy: disarmament by discretion.

The 1930s and 1960s: Consolidation of Discretion

The Firearms Act of 1937 extended controls, requiring certificates for shotguns under certain circumstances and granting police greater authority to deny licences. This was followed by the Firearms Act of 1968, a consolidating statute which remains the backbone of British firearms law today. It created new categories of prohibited weapons, introduced the shotgun certificate (a lesser form of control than full firearm licences), and formalised police powers.

Throughout this period, the concept of self-defence eroded as a legitimate reason for ownership. Though never explicitly banned, it became functionally impossible to claim. By the 1970s, the British Home Office guidance to police made clear: personal protection was not a “good reason.”

Hungerford and Dunblane: Crisis as Catalyst

The modern era of strict gun control began with two tragedies.

- In 1987, Michael Ryan killed 16 people in the town of Hungerford using legally held semi-automatic rifles and pistols. The government responded with the Firearms (Amendment) Act 1988, which banned most semi-automatic centre-fire rifles and restricted pump-action weapons.

- In 1996, Thomas Hamilton murdered 16 children and a teacher at Dunblane Primary School using legally owned handguns. The public outcry led to the Firearms (Amendment) Acts of 1997, which banned private handgun ownership in Great Britain entirely. Only Northern Ireland, with its different legal context, retained limited defensive access.

The 1997 Acts marked the end of armed self-defence in Britain. What had begun in 1689 as a right against tyranny had become, by 1997, a prohibition to avoid liability.

21st Century: The Age of Pre-Emption

Subsequent legislation has focused on pre-emption, imitation, and public perception. These include:

- The Violent Crime Reduction Act 2006: targeted imitation firearms, air weapons, and underage possession.

- The Policing and Crime Act 2017: updated definitions of deactivated weapons, banned certain high-velocity types, and tightened antique firearms regulations.

- The Offensive Weapons Act 2019: introduced knife crime and corrosive substance regulations but also included further restrictions on rapid-fire devices and home delivery of weapons.

Northern Ireland remains the exception, though even there, personal protection weapons are limited to those at “verifiable specific risk,” such as judges, politicians, or security contractors.

When put into a timeline of banning, the reality becomes stark.

- 1920 – Handguns and rifles brought under certification.

- 1937 – Fully automatic weapons banned.

- 1968 – Restrictions on shotguns and imitation firearms.

- 1982 – Age restriction and sale controls on crossbows.

- 1988 – Semi-automatic rifles banned; shotguns with large magazines restricted.

- 1991 – Restrictions on flick knives, gravity knives, martial arts weapons.

- 1996 – Ban on offensive imports like knuckledusters, swordsticks, death stars.

- 1997 – Virtually all handguns banned.

- 2006 – Ban on realistic imitation firearms and restrictions on airsoft/replica sales.

- 2008 – Samurai swords banned (curved swords over 50 cm, with exemptions).

- 2019 – Ban on possession of zombie knives, cyclone knives, knuckledusters, death stars, flick knives, telescopic truncheons, and sale of corrosive substances to under-18s.

- 2021 – Extended zombie knife and rapid-firing rifle bans.

- 2023 – Further categories of zombie-style knives and machetes prohibited.

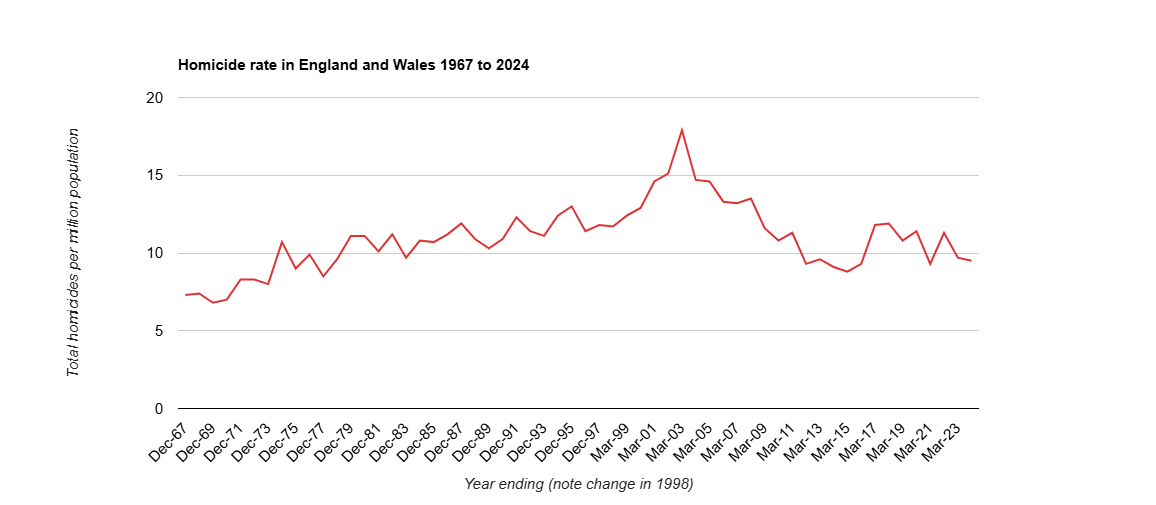

Did it work? No.

The Current Regime: Privilege, Not Right

Today, Britain’s firearm law is among the most restrictive in the democratic world. It is defined by:

- A blanket denial of self-defence as a legitimate reason for gun ownership.

- Complete bans on handguns and semi-automatic rifles.

- Police discretion as the arbiter of access—not courts or fixed rules.

- Tiered certification for shotguns and rifles, requiring safe storage, references, inspections, and renewal.

The result is a system where a farmer can possess a shotgun to shoot foxes but not defend his home. A pistol shooter can practice at a club but cannot legally transport the firearm home. An elderly woman can be beaten in her flat while her family is prosecuted for possession of pepper spray:

Section 5(1)(b) of the Firearms Act 1968 categorises self-defence devices as "banned" weapons, as they are:

designed or adapted for the discharge of any noxious liquid, gas or other thing, or any weapon of whatever description designed or adapted for the discharge of any noxious electrical charge.

In 2004, Tasers were introduced for UK police, but civilian use was already illegal under the same prohibition.

It is, in short, a regime of dependence: protection outsourced to overstretched police services, in the hope crime does not reach you before they do.

The United States: Rights, Realities, and Repercussions

In the U.S., the legal situation is constitutionally protected and conceptually clear – but the empirical landscape is far more complicated. In 2023 alone, 46,728 firearm-related deaths were recorded across the country. Of these, 27,300 were suicides – the highest number ever recorded – and 17,927 were homicides. Contrary to popular media focus, the overwhelming majority of firearm homicides were committed with handguns, not rifles.

Rifles, particularly the AR-15, have become lightning rods for symbolic politics. Often misrepresented as "assault rifles," these are, in reality, semi-automatic firearms with civilian configurations. Automatic weapons have been severely restricted in the United States since 1986. Despite the notoriety of incidents like the Parkland shooting, FBI data from as far back as 2016 confirms the trend: 7,105 firearm homicides were committed with handguns, while only 374 involved rifles of any kind – including AR-style models.

To put it another way, Americans are statistically more likely to be killed by an unarmed assailant than by a rifle.

Yet the deeper complexity lies not in the firearms themselves but in who uses them, and where. Gun violence in the United States is highly localised. A 2014 Crime Prevention Research Centre study found 50 percent of all U.S. murders occurred in just three counties: Los Angeles (California), Cook County (Chicago, Illinois), and Washington D.C. – all jurisdictions with some of the strictest gun laws in the country.

These areas also have something else in common: large, impoverished Afro-American populations, where economic inequality, gang culture, and broken institutions combine to produce a high incidence of gun-related violence.

Federal Bureau of Investigation and Department of Justice data has consistently shown African-American males aged 15–34, while representing only a small fraction of the national population, are involved in over a third or even a half of gun homicides as either victims or perpetrators.

This is not a statement of racial essentialism, but a statistical reality born of social context. Generations of young black men in cities like Chicago, Baltimore, and St. Louis have grown up in communities where carrying a gun is not an option, but a social necessity. Law enforcement, either mistrusted or outmatched, rarely intervenes in time. The state has abdicated its monopoly on force – and into that vacuum steps the individual with a pistol.

It is in this context that American gun violence must be understood. The U.S. is not a monolith but a continent-sized federation, where Wyoming and West Baltimore share little but currency. It is unhelpful – even dishonest – to speak of the United States as a single case study.

Europe’s Mixed Legacy: A More Nuanced Comparison

European nations are often held up as exemplars of restrictive gun control policies, and while some certainly merit that designation, the picture is far more varied than activists would admit. Consider Serbia, which boasts the highest rate of gun ownership in Europe – approximately 39.1 firearms per 100 people – and firearm homicide rates which approach those of the U.S. Midwest. Similarly, Montenegro and Bosnia, with relatively high civilian firearm possession, show elevated gun death statistics compared to their Western European counterparts.

Switzerland stands apart as a compelling counter-example. With 27.6 guns per 100 citizens, Switzerland ranks among the most heavily armed societies in the developed world. And yet, it consistently posts one of the lowest firearm homicide rates globally – as low as 0.2 per 100,000 people.

The reasons are cultural and structural: mandatory military service instills respect for weapons, licensing procedures enforce discipline, and a deep-seated civic ethos dissuades casual violence. Crucially, Switzerland does not face the levels of inner-city racialised gang violence or extreme urban inequality which plague U.S. metros.

Australia, often cited by gun control advocates, presents a more ambiguous case. Since its 1996 National Firearms Agreement, self-defence has been removed as a legitimate reason to own a firearm. Still, the nation reports around one gun homicide per 100,000 residents annually.

When scaled against American states with similar population sizes and pro-gun laws, the difference is often marginal. The storyline Australia saw “zero” gun deaths post-ban is not only inaccurate but misleading.

The Red Herring: More Guns Means More Crime

The presumption more civilian guns necessarily mean more gun crime is increasingly difficult to defend in light of comparative data. Within the United States, states like California and Illinois – with some of the most stringent firearm laws – continue to suffer from persistent and deadly gun violence.

Conversely, states like Vermont or regions like rural Texas report high rates of lawful gun ownership and comparatively low firearm homicide rates.

Internationally, Switzerland and the Czech Republic prove regulated gun ownership can coexist with public safety.

The critical variables are not simply the number of guns in circulation but the presence or absence of trust, enforcement, and social cohesion. Gun control without cultural coherence leads to disarmament without deterrence.

It is the law-abiding, not the lawless, who surrender their arms.

In sum, the United States suffers from a uniquely urban and racialised form of firearm violence, largely disconnected from the legal question of ownership. Meanwhile, Europe – particularly Switzerland – demonstrates an armed populace is not inherently a violent one. The difference lies in the moral fabric, the civic expectation, and the willingness of the state to trust its citizens.

To argue European nations cannot sustain a reformed right to bear arms because of American outcomes is to ignore the data.

Remove the most violent urban areas of the United States from the equation, and its gun homicide rate plummets to levels comparable with Eastern Europe. Without America’s inner-city gang violence – and particularly, without its uniquely Afro-American gun subculture – the premise of widespread civilian disarmament loses its moral urgency.

For Britain, which shares more with Switzerland than with St. Louis, the lesson is clear: a right to bear arms need not mean a right to chaos.

It can mean a right to responsibility – if only we choose to reclaim it.

The English Self-Defence Act

The English Defence Bill marks a proposed return to the fundamental civic principles long embedded in England’s legal and constitutional tradition. Unlike previous firearms legislation, which incrementally chipped away at the individual’s capacity for lawful self-defence, ESDA seeks to affirm a negative liberty to defend life, family, and home within a disciplined and well-regulated framework.

Origins and Inspiration

ESDA is a product of ongoing policy research into comparative legal models, drawing on the Canadian Possession and Acquisition Licence (PAL), U.S. 'may-issue' licensing regimes, and the federalist balance that allows U.S. states to craft bespoke answers.

But the intellectual heritage of ESDA is emphatically English. It rests on the constitutional foundations of common law, the 1689 Bill of Rights, and the recognition self-defence is not a privilege bestowed by statute, but a negative natural right subject only to proportionality and necessity.

The arguments for civilian ownership of weapons are quite simple, numerous, and well-established.

- One has a right to protect oneself, family, and property when threatened, which precedes government and politicians cannot legislate away.

- The ancient Common Law right descends from the medieval obligation and right of freemen to bear arms for the realm's defense.

- Citizen-soldiers historically defended England without standing armies.

- Parish constables and citizens historically maintained order together.

- Hunting rights have been tied to land ownership and social status for centuries.

- Charles I's disarmament attempts led to tyranny; armed citizens prevented royal overreach.

- Landowners' have always had the right to defend estates from poachers, rioters, and criminals.

- Police can't be everywhere: the average response time leaves citizens vulnerable.

- Elderly, disabled, and smaller individuals gain protection they did not previously have.

- Criminals avoid targets who might be armed.

- Firearms are essential for predator control, hunting, and remote area security.

- Weapons provide protection during civil breakdown when law enforcement fails.

Core Provisions

At its heart, ESDA establishes a new regulatory category – the Defence Firearm Certificate (DFC). The DFC is designed to offer qualified, thoroughly vetted citizens the ability to lawfully own and carry firearms for personal protection under stringent safeguards. The criteria include:

- Mandatory GP clearance: Applicants must receive medical certification verifying they pose no significant risk of self-harm or violence, renewed periodically.

- Background checks: Comprehensive checks including criminal history, domestic violence records, and affiliations with extremist groups.

- Tiered licensing: Carriage rights are divided into categories: transport-only, concealed carry, and limited open carry, depending on training level and situational need.

- Training and assessment: Applicants must pass an intensive competency and safety course, modelled on Canada’s PAL system and U.S. concealed carry training, including live-fire drills and legal instruction.

Where ESDA Breaks New Ground

The Act proposes a radical shift from prohibition to stewardship. It recognises citizens in rural or under-policed areas deserve the capacity to protect themselves. The Act would:

- Repeal and replace the 1968 Firearms Act and its amendments (1988, 1997), which have produced a confusing and often contradictory regulatory regime.

- Codify the doctrine of proportionality, offering clarity for courts and citizens alike on when defensive force is lawful.

- Establish clear restricted zones, such as polling stations, schools, and licensed alcohol venues, where carriage is prohibited.

- Introduce strong deterrents against misuse, including mandatory minimum sentencing for unlawful discharge, brandishing, or storage violations.

A Balance of Liberty and Order

ESDA rejects both libertarian absolutism and disarmament paternalism. It offers a model of arms-bearing as a duty as much as a right – requiring education, responsibility, and civic engagement. It re-establishes the armed citizen not as a rogue actor but as a lawful auxiliary to peacekeeping.

It is important to note that under the ESDA, self-defence would remain bounded. The right to armed response would only apply under immediate threat of grave harm. Force must be reasonable and proportionate. Any ambiguity about these limits would be addressed through statutory guidance and case law, drawing on existing principles in criminal and tort law.

Constitutional Rearrangement

ESDA also includes a symbolic and legal realignment. It recognises the present regime – in which police may take hours to respond to emergencies, while citizens are criminalised for defending themselves – is not only inefficient but unjust.

In a climate of rising rural crime, delayed police response times, and growing public concern about knife and gang violence, ESDA answers a simple question: if not the citizen, then who?

This law does not attempt to copy the American Second Amendment wholesale. Instead, it aims to restore an English tradition of civic defence – moderated by accountability, framed by legality, and informed by centuries of precedent.

Who Qualifies?

The DFC is not a blanket right. It is aimed at those with a demonstrable need for protection, including:

- Rural residents in areas with delayed police response.

- Former service personnel with retained competency.

- Licensed business owners transporting high-value goods.

- Persons with the required competencies and wellness.

- Persons under verified threat (e.g., whistleblowers, stalking victims).

In this way, the law balances access with scrutiny. It empowers those at risk while preventing general proliferation.

A Restoration, Not a Revolution

The English Defence Bill represents not a rupture with tradition but a restoration of it. It rediscovers an old truth – that the first line of defence is not the constable or the court, but the citizen. And it does so with the maturity and legal rigour that has long been a hallmark of the English constitutional order.

The Restorationist vision is one in which liberty and order coexist, where the state does not monopolise security but shares it with responsible citizens. In that spirit, ESDA is not merely a firearms bill. It is a statement of trust in the people, and a defence of the ancient liberties that once made England free.

The Bill of Rights 1689 did not, in its purpose, intend to arm those who have newly entered Britain, it was intended for the defence of the Englishman, Welshman and Scotsman. If they were to walk into a bar, the barkeep would explain that they may be served.

Regulation Without Disarmament: A Third Way

This is no libertarian fantasy. It is a conservative constitutional settlement. ESDA does not "glorify" firearms – it regulates them sensibly. But it trusts citizens as participants in their own safety, rather than passive wards of an overstretched state.

The Act defines firearms classes, sets safe storage standards, and introduces stiff penalties for misuse. But it permits the average citizen – if vetted and trained – to own and carry a defensive arm. In so doing, it ends the bizarre hypocrisy of a system which trusts a farmer with a shotgun but not a parent with a pistol.

The Moral Dimension: Trust in the Citizen

The central question is not one of statistics, but of trust. Is the English citizen to be forever shielded and policed – or permitted to prepare, to act, to defend? Are we adults in a free society, or wards in a state-run nursery?

Civic culture depends on shared responsibility. ESDA affirms defence is not merely the state’s monopoly. It is a shared duty, grounded in law, but animated by liberty.

The Restoration of Balance

If successful,ESDA could offer a blueprint for nations struggling to balance safety and sovereignty. It reminds us that law-abiding citizens are not the problem. And that the right to defend life and home is not a colonial relic – but a civic necessity.

This Act is not about emulating America. It is about restoring England.

Gun policy cannot be solved by panic or by platitude. Rights without regulation are dangerous. But regulation without rights is tyranny in waiting. ESDA offers a way forward – one rooted in memory, in principle, and in trust.

The liberty to defend oneself is not a luxury. It is a necessity of nationhood. And the defence of liberty, as ever, begins at home.