The Unity Act: A New Parliament, Devolved Upper Houses, No ECHR or Councils

Abolish the Lords. Relocate Parliament to the geographic centre. Bind all nations through one lower house. Let each control local application through separate upper houses. End devolution's chaos. Build a constitutional structure capable of absorbing a hundred territories without amendment.

Four distinct nations bound together in the crucible of Parliament. For three centuries this union worked, not because Westminster was perfect, but because it was singular. Then came 1998. Tony Blair's devolution settlements fractured the constitutional order, creating competing centres of democratic authority without establishing any hierarchy between them. Scotland got a parliament. Wales got an assembly. Northern Ireland got Stormont and its endless power-sharing collapses. England got nothing, and Westminster became both national and federal legislature in a muddle nobody could explain.

Eighty-five per cent of the union lives in England, so England wins every Westminster vote. London sucks resources and attention from every region. Scottish nationalists point to this imbalance as proof they need independence. Wales remains constitutionally inferior to Scotland, incorporated by conquest rather than treaty. Northern Ireland's institutions collapse whenever republicans and unionists fall out. Meanwhile, the House of Lords has swollen to over 1,600 partisan appointees, making it the second-largest legislative chamber on Earth after the Chinese National People's Congress.

We cannot wind back the clock and shut down Holyrood or the Senedd. Those institutions have democratic legitimacy now. Nor can we tolerate calls for an English parliament, which would only deepen the fracture. The answer is not more division but a fundamental restructuring: one lower house binding all territories together through shared legislation, separate upper houses allowing each nation to control how laws apply locally, and a geographic relocation to the centre of the United Kingdom.

This is not federalism in the American sense, where states can ignore federal law. Reserved matters—defence, foreign affairs, currency, borders—apply everywhere. But for general legislation, each territory decides whether to ratify. A banking regulation might suit London and Edinburgh but prove unworkable in Jersey or a future charter city in the South Atlantic. The territory opts out. Democracy without uniformity.

The Unity Act transfers existing powers rather than inventing new ones. It abolishes the Lords entirely. It relocates Parliament from London to Derbyshire, near the geometric centroid of Britain. It creates a structure capable of absorbing a hundred new territories over the coming century—charter cities, special economic zones, leased islands—without requiring constitutional amendment each time. Most radically, it abolishes every tier of local government between Parliament and the parish, devolving power downward whilst binding the nations together at the top.

Read the draft Unity Act written by Alex Coppen in full here (374 pages):

Understanding the Unity Act: Constitution At Scale

The Unity Act represents the most comprehensive constitutional transformation in British history since the Acts of Union. Spanning 200+ sections across 13 parts with 23 detailed schedules, this legislation fundamentally restructures parliamentary governance, territorial administration, rights protections, and the relationship between the constituent nations of the United Kingdom and its overseas territories.

The Act abolishes the House of Lords and all existing devolution arrangements, replacing them with a federal-unitary hybrid system featuring a population-weighted Lower House and multiple revising Upper Houses. It dismantles the entire apparatus of local government in favour of parish-level administration, withdraws from the European Convention on Human Rights whilst establishing domestic protections for natural liberties, and relocates Parliament from Westminster to the geographic centroid of Britain. The implementation timeline extends across 13 years, with full parliamentary operation commencing in Year 13.

The Act fundamentally reconceives parliamentary sovereignty by distributing legislative revision power across national and territorial upper houses through a novel "round-robin ratification" process, whilst maintaining the primacy of the directly elected Lower House.

It creates an infinitely scalable constitutional framework capable of incorporating new territories without structural amendment, establishes mechanisms for territorial acquisition and governance, and preserves British sovereignty whilst accommodating diverse local arrangements. The legislation transfers existing governmental powers rather than rewriting them wholesale, ensuring legal continuity throughout the transition.

Part 1: Preliminary Provisions

The opening sections establish the Act's title, define its constitutional status as an entrenched statute immune from implied repeal, and set forth comprehensive definitions governing the entire legislative scheme. The Act takes effect in phases according to Schedule 1, with certain provisions operative immediately upon Royal Assent, major institutional abolitions occurring in Year 11, and full parliamentary operation achieved by Year 13.

Critical definitions establish the Britannic Parliament as comprising His Majesty, the Lower House, the National Upper Houses, and Territorial Upper Houses in their respective capacities. The Lower House is defined as the directly elected chamber with population-weighted representation. National Upper Houses refer to the four chambers for England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Territorial Upper Houses encompass the converted local assemblies of any territory under British sovereignty. The concept of "round-robin ratification" receives precise definition as the sequential consultation process whereby bills approved by the Lower House must be transmitted to all upper houses for consideration. Reserved matters and devolved matters receive categorical distinction, with exhaustive lists provided in subsequent schedules.

The territory tier classification system receives foundational definition, establishing four tiers based on population and strategic significance. The override power, whereby the Lower House may compel application of legislation to territories whose upper houses have declined ratification, receives specification requiring a two-thirds majority. Category A, B, and C legislation distinctions are defined, determining different review periods and ratification requirements.

Part 2: Repeal and Abolition

This Part systematically dismantles the existing constitutional architecture to create a clean slate for the new arrangements. The abolition proceeds in three chapters addressing human rights law, the House of Lords, and devolution arrangements respectively.

The first chapter repeals the Human Rights Act 1998 in its entirety and withdraws the United Kingdom from the European Convention on Human Rights. The denunciation of treaty obligations follows established international procedures, with appropriate diplomatic notice periods. Transitional provisions address pending cases before the Strasbourg Court, transferring jurisdiction to domestic courts where British nationals are concerned. The repeal operates without creating any gap in rights protection, as the new Bill of Rights based on natural liberties becomes operative simultaneously. Consequential amendments update thousands of statutory references to the HRA and ECHR framework.

The second chapter abolishes the House of Lords as a legislative chamber. The dissolution is complete rather than reformist in character. All 1,600-plus existing peers lose their legislative functions, though ceremonial titles and honours continue to exist without parliamentary privilege. The provisions address the fate of Lords Spiritual, the Church of England bishops who historically sat in the Lords, removing their legislative role whilst respecting the constitutional position of the Established Church. Hereditary peers, life peers, and Lords of Appeal in Ordinary all cease to have any parliamentary function. Generous pension arrangements recognise past service. No peers transfer automatically to the new system, though former Lords may stand for election to the Lower House or seek appointment to upper houses under whatever selection methods those chambers adopt. The administrative staff of the House of Lords transfer to appropriate successor bodies. Archives and records pass to appropriate custodians. Pending legislation in the Lords at the time of abolition either receives expedited passage or lapses according to specified procedures.

The third chapter repeals the Scotland Act 1998, Government of Wales Acts, and Northern Ireland Act 1998, abolishing the Scottish Parliament, Welsh Senedd, and Northern Ireland Assembly as currently constituted. The existing powers of these institutions do not evaporate but rather transfer to the new National Upper Houses for Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland respectively. All staff of the abolished institutions transfer to the successor upper houses, remaining in Edinburgh, Cardiff, and Belfast. The buildings and facilities continue in use. The legislation currently enacted by the devolved bodies remains in force, treated as if passed by the new upper houses, ensuring legal continuity. Future amendments proceed through the round-robin process.

Part 3: Establishment of The Britannic Parliament

This Part creates the new parliamentary structure across five chapters addressing the Lower House, National Upper Houses, Territorial Upper Houses, legislative procedures, and the Bill of Rights respectively.

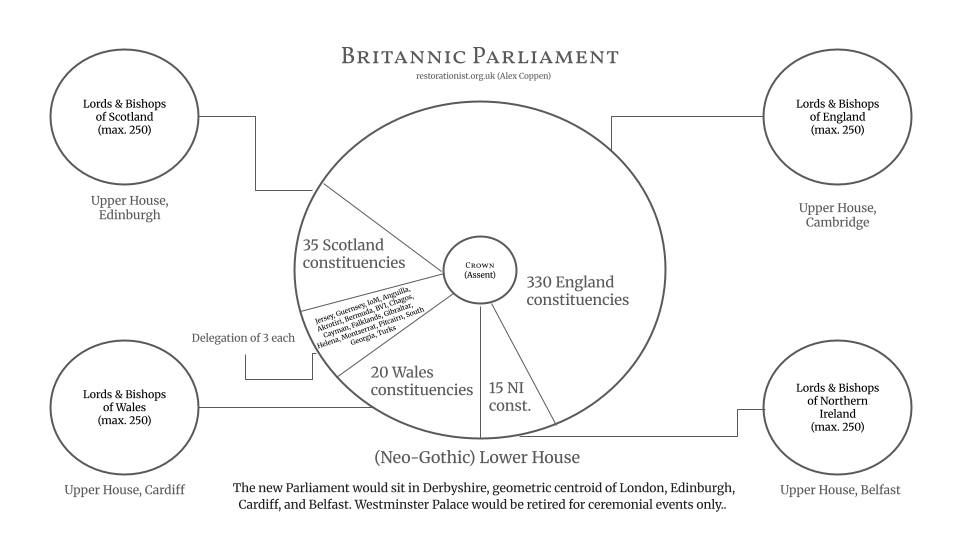

The Lower House consists of 400 members elected from single-member constituencies distributed across the four nations according to population. England receives 330 seats, Scotland 35, Wales 20, and Northern Ireland 15. The boundaries are specified in Schedule 5, drawn with mathematical precision to ensure equal population per constituency within each nation. The voting system employs simple plurality in single-member districts. The term of the Lower House is five years, subject to earlier dissolution by royal proclamation on the advice of the Prime Minister following either a vote of no confidence or a two-thirds vote for early dissolution. The Speaker is elected by secret ballot and must resign all party affiliations upon taking office. The Lower House possesses exclusive authority to initiate all primary legislation and holds final authority over money bills. Ministers must maintain the confidence of the Lower House. The chamber inherits all historic privileges and powers of the House of Commons, adapted to the new constitutional framework.

The National Upper Houses receive detailed treatment across four sections addressing England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. The Upper House of Scotland consists of members selected by a method to be determined by the Scottish people through a consultative process, with options including direct election, indirect election by local representatives, or appointment by committees. The size is initially set at 129 members, matching the former Scottish Parliament, though this number may be adjusted. The Upper House sits in Edinburgh, inheriting the Holyrood building and all facilities of the former Scottish Parliament. It possesses all powers previously exercised by the Scottish Parliament over devolved matters, now exercising them through the round-robin process. The Welsh and Northern Irish upper houses receive parallel treatment, sitting in Cardiff and Belfast respectively, with Wales having 60 members and Northern Ireland 90 members initially.

The Upper House of England presents unique complexity given England's size and the absence of any predecessor body. A transitional Upper House of England operates for the first three years, composed of appointed members drawn from former Lords, local government leaders, and distinguished persons. This transitional body conducts extensive consultations with the English people regarding the permanent composition method. Proposals are developed for consideration by the Lower House in Year 3, with implementation following approval. The permanent upper house may be elected, appointed, or use a mixed system as determined through this consultative process. Location is determined by a competitive process among English cities, with a new purpose-built chamber to be constructed. The size is initially set at 533 members but may be adjusted when the permanent arrangements are established.

Territorial Upper Houses receive specification through a scalable framework accommodating territories of vastly different sizes and governance capacities. The tier system establishes four classifications with corresponding representation and autonomy. Tier 1 territories, having populations exceeding 50,000 or receiving strategic designation, possess full upper house status with elected or appointed chambers, complete authority over devolved matters within their jurisdiction, and representation in the Lower House. Tier 2 territories, with populations between 10,000 and 50,000, have advisory councils transitioning to elected bodies, limited devolved authority, and representation in the Lower House. Tier 3 territories, with populations below 10,000, have advisory councils without legislative authority, with most governance provided directly by central departments, and guaranteed minimum representation of three seats in the Lower House. Tier 4 comprises specially administered territories, including military bases, Antarctic claims, and uninhabited islands, governed directly by appointed administrators with no local legislative body or Lower House representation.

The representation formula allocates Lower House seats to territories through a base-plus-milestone system. Every territory, regardless of size, receives a minimum of three seats ensuring voice in Parliament. Additional seats are awarded at population milestones, with allocations increasing as populations grow. A territory reaching 10,000 inhabitants gains a fourth seat. At 25,000, two additional seats are added for a total of six. This progression continues through specified thresholds, with the largest territories potentially holding 160 or more seats. The formula ensures proportionality whilst preventing the smallest territories from being entirely without voice.

Legislative procedures operate through the round-robin ratification system, detailed exhaustively in Schedule 6. Bills originate in the Lower House, where they undergo the traditional three readings, committee stage, and report stage before final passage. Upon passage, the Speaker certifies the bill and categorises it as Category A (constitutional and reserved matters), Category B (general legislation on devolved matters), or Category C (optional frameworks for local adoption). The bill is then transmitted simultaneously to all upper houses within seven days.

Each upper house has a review period to consider the legislation: 90 days for Category A, 60 days for Category B, 30 days for Category C, and 14 days for emergency legislation. During this period, the upper house conducts its own readings, committee consideration, debates, and amendments. At the conclusion, each upper house votes on one of three options: ratify the bill for application in its territory, reject the bill preventing application in its territory, or propose amendments with conditional ratification.

When all upper houses have voted or the time periods expired, the Lower House receives a comprehensive report. If all upper houses ratify, the bill proceeds directly to Royal Assent and applies universally. If some upper houses reject, the Lower House has several options. For isolated rejections, it may accept non-application in those territories, creating asymmetric legislation. Alternatively, it may invoke override power, requiring a two-thirds majority to compel universal application. If the override succeeds, the law applies everywhere regardless of rejections. If it fails, the law does not apply in rejecting territories.

Category A legislation, concerning reserved matters and constitutional questions, requires either 75 per cent ratification by upper houses or a two-thirds override by the Lower House. These matters must apply uniformly across the entire union to maintain constitutional integrity. Examples include declarations of war, constitutional amendments, currency changes, and foreign treaty ratifications.

Money bills follow a distinct process. The Lower House has exclusive authority to originate bills imposing taxes or authorising expenditure. The Speaker certifies them as money bills. Upper houses receive them for 30-day consultation periods but cannot reject or amend, only offer advisory opinions. Money bills proceed to Royal Assent regardless of upper house views, preserving the historic principle of Commons financial supremacy.

The round-robin process accommodates amendments through a structured procedure. When an upper house proposes amendments, these are transmitted to the Lower House within seven days of completing the round-robin. The government or bill sponsor responds by either accepting the amendments, proposing compromise modifications, or rejecting them entirely. If amendments are accepted, the modified bill returns to all upper houses for 14-day confirmation votes. If confirmed, the bill proceeds to Royal Assent. If the Lower House rejects proposed amendments, the requesting upper houses may maintain their rejection of the bill.

The Bill of Rights receives comprehensive treatment in Schedule 2, establishing 15 natural liberties as constitutional protections. These liberties are characterised as negative rights, operating as prohibitions on governmental action rather than entitlements to services or resources. They include freedom from coercive sovereignty surrender, freedom from coercive social engineering, freedom from enforced outcome equality, freedom from compelled speech, freedom of obscurity (the right to be forgotten), freedom from medical coercion, freedom of biological immutability, freedom of biological separateness, freedom from historical guilt, freedom from malicious commercialisation, freedom from mass surveillance, freedom from censorship, freedom from indoctrination, freedom from serious immigration crime, and freedom from automation replacing human judgment in sensitive areas.

Each natural liberty receives precise definition specifying its scope and any permissible limitations. The liberties are directly enforceable in courts without implementing legislation. No administrative bodies, commissions, tribunals, or ombudsmen are established to oversee their operation. Enforcement occurs exclusively through ordinary judicial review in existing courts. Any law, regulation, or governmental action violating a natural liberty is void to the extent of the violation. Parliament may expressly limit liberties within the terms specified for each, but such limitations require explicit statement and cannot occur by implication or administrative action.

Part 4: Abolition of Local Government

This Part eliminates the entire apparatus of English local government across three chapters, addressing counties, districts, parishes, and devolution of functions. Similar provisions apply to Scottish, Welsh, and Northern Irish local authorities mutatis mutandis.

All county councils, unitary authorities, district councils, borough councils, city councils, metropolitan councils, and London boroughs are abolished. The abolition is absolute, occurring on a specified date in Year 11. All councillors cease to hold office on that date, with no transfer to successor bodies. Approximately 20,000 elected local councillors lose their positions. Staff, estimated at 1.5 million employees across all local authorities, face either transfer to central government departments, transfer to parish councils for limited functions, or redundancy with statutory compensation.

Parish councils receive substantial enhancement, becoming the sole form of sub-national government within each nation. Every area of England is assigned to a parish. Urban areas previously lacking parishes receive newly constituted bodies. Parish boundaries are redrawn using mathematical precision to ensure populations between 2,000 and 15,000 inhabitants per parish, creating approximately 5,000 to 7,000 parishes nationally. Each parish council consists of 7 to 15 elected members serving four-year terms, elected by simple plurality in multi-member wards. Councils elect their own chairs and vice-chairs from among members.

Parish council functions are strictly limited to genuinely local matters. They may maintain public spaces including parks, gardens, commons, and recreation grounds. They may provide and maintain bus shelters, public seating, notice boards, and similar street furniture. They may operate community centres, libraries, and similar facilities. They may grant small community grants to local organisations. They may comment on planning applications affecting their area, though decisions rest with national planning authorities. They may organise local events, ceremonies, and celebrations. They may maintain war memorials and similar monuments. They exercise common law powers to protect local amenities and public health at the most immediate level.

Crucially, parish councils possess no powers over education, social services, housing, major planning decisions, economic development, public transport, police, fire services, or any significant governmental function. These responsibilities transfer to national ministries or are eliminated entirely.

The devolution of functions follows a systematic approach. Education transfers entirely to the Ministry of Education, operating through regional and local offices but under unified national policy and standards. Social services, including children's services and adult social care, transfer to the Ministry of Health and Social Care, with regional administration. Housing policy and social housing provision transfer to national authorities, though operation may be contracted to housing associations. Planning authority for all but the most trivial applications transfers to a national Planning Inspectorate operating through regional offices. Public transport, where not operated by private companies, comes under national transport authorities. Police and fire services consolidate into larger regional forces under national frameworks. Waste collection and disposal become the responsibility of private contractors under regional frameworks or national authorities.

The financial implications are substantial. Local government currently accounts for approximately 25 per cent of total public expenditure. Most functions continue but under national administration, requiring reorganisation rather than elimination of spending. Savings arise from eliminating approximately 400 separate bureaucracies, reducing duplicated overhead costs, and streamlining administration. Parish councils receive modest budgets sufficient for their limited functions, raised through small precepts on national property taxes.

Part 5: Territorial Governance and Expansion

This Part establishes mechanisms for acquiring and governing territories beyond the existing United Kingdom, structured across six chapters addressing the Britannic Territorial Office, territorial acquisition, governance frameworks, economic zones, citizenship, and representation.

The Britannic Territorial Office operates as an executive agency under the Foreign Secretary, responsible for administering all British Overseas Territories, facilitating territorial expansion, managing relationships with territorial governments, and operating the territory tier classification system. The BTO maintains offices in London and regional centres, staffed by career administrators with expertise in colonial administration, development economics, and international law. Its functions include processing petitions from territories seeking British sovereignty, conducting due diligence on acquisition proposals, administering territories during transitional governance periods, providing technical assistance to territorial governments, certifying tier classifications and advancements, managing development funds for territorial infrastructure, and coordinating between territorial governments and Westminster.

Territorial acquisition follows specified pathways. Voluntary accession occurs when a recognised polity petitions for British sovereignty, provides evidence of popular support through referendum or equivalent, satisfies due diligence requirements regarding legitimacy and governance capacity, and receives approval from both Houses of Parliament (Lower House and relevant national upper houses). Purchase acquisition proceeds through negotiations with vendor states, approval by Parliament and the Crown, payment of consideration, and formal transfer of sovereignty. Treaty acquisition involves international agreements ceding territory, ratification by Parliament, and implementation. Discovery and settlement allows claiming of terra nullius, uninhabited islands, and similar territories following international law principles. Each pathway includes safeguards against improper acquisition and ensures legitimate transfer of sovereignty.

Governance frameworks vary by tier. Tier 1 territories possess full internal self-government with elected legislatures or appointed councils functioning as upper houses, governors representing the Crown with limited reserve powers, internal authority over all devolved matters, participation in round-robin revision for laws affecting them, and full representation in the Lower House. Tier 2 territories have transitional advisory councils moving toward elected bodies, governors exercising more active administrative roles, limited devolved authority with most functions exercised by the BTO, and representation in the Lower House. Tier 3 territories receive direct administration by BTO-appointed governors, advisory councils providing local input, minimal autonomous authority, and guaranteed minimum Lower House representation of three seats. Tier 4 territories have administrators rather than governors, no local legislative bodies, direct metropolitan governance, and no Lower House representation except through special provisions for any resident populations.

Charter cities receive extensive treatment as a mechanism for experimental governance. Parliament may designate areas within existing territories or newly acquired lands as charter cities, granting them special constitutional status with bespoke governance arrangements, regulatory autonomy, and ability to establish distinct legal frameworks within specified parameters. Charter cities must remain subject to reserved matters, respect natural liberties, maintain common citizenship, and uphold basic rule-of-law principles, but otherwise enjoy broad autonomy to create competitive regulatory environments. Examples might include financial centres operating under distinct commercial codes, technology hubs with specialised IP regimes, or retirement communities with age-restricted governance. The charter city framework enables innovation whilst maintaining territorial integrity.

Special economic zones complement charter cities by offering areas with distinct tax regimes, streamlined regulations, and enhanced investment incentives whilst maintaining normal governance structures. Territories may establish SEZs to attract capital and development, operating under frameworks approved by Parliament.

Citizenship provisions establish British citizenship as a unified status held equally by all persons in all territories. Territories cannot create separate citizenships or restrict movement of British citizens between territories. Birth in British territory generally confers citizenship, with provisions for descent and naturalisation. Citizens possess equal rights throughout British domains, including rights to reside, work, own property, vote, and access public services subject to reasonable residency requirements. The unified citizenship binds the territories together constitutionally and prevents fragmentation.

Representation in the Lower House follows the formula specified in Schedule 10, ensuring all territories regardless of size possess meaningful voice in Parliament. The smallest territories hold three seats, providing influence disproportionate to population but ensuring they are not entirely marginalised. Larger territories gain additional seats at population milestones, gradually approaching proportional representation as populations grow. This graduated system balances the principle of representation by population with recognition of territorial identity and the need to prevent domination by the largest territories.

Part 6: New Parliamentary Facilities

This Part addresses the physical relocation of Parliament across three chapters concerning the new parliamentary complex, Westminster Palace's future role, and transitional arrangements.

The location of the new Parliament is determined by geometric calculation, identifying the centroid of London, Edinburgh, Cardiff, and Belfast. This point lies in Derbyshire, approximately in the area of Ashbourne or Matlock. The exact site is selected through a competitive process among local authorities in the region, evaluating land availability, transport connections, environmental impact, cost, and community support. The selected location receives designation in Year 2, with construction commencing immediately.

The architectural character embraces neo-Gothic design, drawing on the Victorian Gothic tradition of the Palace of Westminster whilst incorporating modern functionality. The complex includes a chamber for the Lower House accommodating 400 members with supporting facilities, offices for all members and ministers, committee rooms for detailed legislative work, a Royal Gallery for ceremonial occasions, facilities for the press and public, extensive archive and library space, and secure conference facilities. The design ensures accessibility, environmental sustainability, and technological integration whilst respecting British architectural heritage.

Westminster Palace ceases to function as the working parliament, transitioning to ceremonial and educational use. State Opening of Parliament continues there annually, with the monarch proceeding in state to deliver the Speech from the Throne in the historic House of Lords chamber. The building becomes a UNESCO World Heritage site if not already designated, open to extensive public visitation. Educational programs utilise the historic chambers to teach parliamentary history and constitutional principles. The British Diplomatic Institute occupies portions of the palace, training future diplomats in the historic rooms where Britain's global role was shaped. The British Institute of Statesmanship provides office space for fellows studying constitutional questions. International conferences and summits may use the facilities on occasion. The palace remains Crown property under parliamentary trusteeship, preserved for the nation.

Transitional arrangements manage the migration from Westminster to Derbyshire across Years 11-13. Parliament continues sitting in Westminster through Year 10 whilst construction proceeds in Derbyshire. The final session in Westminster occurs with appropriate ceremony marking the end of an era. During Year 11, parliamentary functions transfer to the new complex, with members, staff, and equipment relocating. The first session in the new Parliament occurs with grand ceremony, including Royal attendance and appropriate recognition of the historic significance. Staff receive relocation assistance including moving expenses, housing support, and family assistance to ease the transition.

Part 7: Judicial and Legal Continuity

This Part ensures the legal system continues functioning without disruption across four chapters addressing courts, judiciary, legal profession, and law continuity.

The Supreme Court continues its functions unaltered, remaining the highest court for civil matters and the constitutional court for devolution and human rights questions under the new framework. Its composition, appointments process, and jurisdiction continue unchanged except for modifications required by the new constitutional structure. References to the ECHR in its jurisprudence are superseded by the natural liberties framework. The Court's location in Parliament Square, London, continues, maintaining accessibility and connection to legal tradition.

The High Court, Court of Appeal, and subordinate courts continue their jurisdictions and operations. The judicial structure requires no fundamental reform, as the courts are already organised on a functional basis suitable to the new arrangements. Minor adjustments address terminology changes and jurisdictional clarifications arising from abolition of local authorities and establishment of new territorial courts.

Judicial appointments continue through the Judicial Appointments Commission, operating under existing statutory frameworks with modifications to address the new territorial structures. Judges in territorial courts are appointed through processes established by territorial upper houses, subject to minimum qualifications and procedural safeguards ensuring independence and competence.

The legal profession continues with minimal impact. Solicitors and barristers practising in England and Wales continue under existing regulatory frameworks, now administered by national authorities rather than quasi-governmental bodies with local government involvement. Scottish and Northern Irish legal professions continue their distinct traditions. Territories may recognise English or local qualifications according to their needs. Rights of audience and practice rights adapt to the new court structures through ordinary professional regulation.

Legal continuity receives emphatic protection through comprehensive savings provisions. All existing legislation, whether primary or secondary, continues in force. Acts of Parliament remain valid and enforceable. Statutory instruments and regulations made under existing powers continue applying. Devolved legislation from the Scottish Parliament, Welsh Senedd, and Northern Ireland Assembly continues, treated as if enacted by the successor upper houses. Local authority bylaws continue at the parish level, with parish councils inheriting the authority to maintain, amend, or repeal them. Licenses, permits, planning permissions, and similar administrative authorisations remain valid despite the abolition of the bodies issuing them. Contracts entered by abolished bodies remain binding on successor entities. Court orders continue in force and remain enforceable.

This comprehensive continuity ensures no legal vacuum emerges. The transition occurs through transfer and reorganisation rather than repeal and replacement, preserving legal certainty and preventing chaos.

Part 8: Financial Provisions

This Part establishes fiscal arrangements across four chapters addressing parliamentary budgets, territorial finances, revenue sharing, and audit mechanisms.

The Lower House and each upper house receive independent budgets determined through processes insulated from executive control. The Lower House budget is set by the Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority operating under statutory mandate, ensuring members' salaries, allowances, and operational costs are adequate without being excessive. Currently, members receive salaries of approximately £90,000 with additional allowances for constituency offices and staff. Under the new arrangements, Lower House members continue receiving comparable remuneration adjusted for inflation and responsibilities.

Upper house budgets are determined by equivalent independent bodies established for each upper house, ensuring operational independence whilst preventing profligacy. Members of upper houses receive remuneration appropriate to their roles, whether full-time or part-time. Full-time members of national upper houses receive salaries comparable to Lower House members, recognising equivalent responsibilities. Members of territorial upper houses receive salaries reflecting local economic conditions and the time commitment required, ranging from modest stipends for part-time members in small territories to full salaries in larger jurisdictions.

The critical principle establishes that no level of government may coerce any other through financial manipulation. The central government cannot threaten to withhold funds to compel upper houses to ratify legislation. Each legislature receives its budget as a matter of right, subject to ordinary accountability and audit but not to political control. This financial independence reinforces constitutional independence and prevents the round-robin process from becoming a charade where economic pressure substitutes for genuine deliberation.

Territorial finances follow the framework in Schedule 15. Each territory contributes to central government costs according to a formula based on population, GDP, and fiscal capacity. These contributions fund reserved functions including defence, foreign affairs, currency, and constitutional courts, benefiting all territories. Revenue sharing provisions return portions of nationally collected taxes to territories according to population-weighted formulas, ensuring adequate resources for devolved functions. Development grants provide additional funding to less developed territories, enabling infrastructure investment and economic advancement. The goal is fiscal balance, where territories contribute fairly to common costs whilst retaining sufficient resources for local needs.

Transparency requirements mandate publication of all financial information. Every budget, account, expenditure, revenue source, transfer, and grant becomes public information, accessible through online databases. Citizens may scrutinise how their representatives spend public money, enabling informed electoral choices and deterring corruption or waste.

Audit and accountability operate through the National Audit Office, examining all parliamentary and governmental expenditure. Each upper house undergoes separate annual audit, with reports published and debated. The Public Accounts Committee of the Lower House scrutinises spending across government, calling witnesses and issuing reports on efficiency, effectiveness, and propriety. Parliamentary Standards Authorities at each level investigate allegations of financial impropriety by members, imposing sanctions including repayment, suspension, or expulsion for serious violations.

Part 9: Rights and Freedoms

This Part codifies the Bill of Rights with detailed treatment of each natural liberty across multiple chapters, each chapter addressing several related liberties.

The first chapter establishes freedom from coercive sovereignty surrender, preventing any government from transferring British sovereignty to international bodies, supranational organisations, or foreign powers without explicit consent. This liberty prohibits Parliament or ministers from pooling sovereignty, subordinating British law to foreign or international law, accepting compulsory jurisdiction of foreign or international courts, or delegating legislative authority to unelected international bodies. Any such transfers require not merely parliamentary approval but national referendum with a two-thirds majority and minimum turnout requirements. The liberty aims to prevent repetition of European Union membership circumstances, where sovereignty gradually eroded through treaty amendments and judicial expansion absent direct popular consent.

Freedom from coercive social engineering prevents governmental attempts to reshape society, culture, or human behaviour according to ideological blueprints. Public authorities cannot implement policies whose primary purpose is altering social attitudes, relationships, or cultural practices rather than addressing concrete material harms. Governments may address genuine threats to health, safety, or public order but cannot pursue egalitarian, perfectionist, or communitarian agendas through state power. Examples of prohibited action include compelled diversity training, social credit systems, mandatory consciousness-raising programs, and policies whose primary aim is changing how people think rather than what they do.

Freedom from enforced outcome equality prohibits governmental action aimed at equalising results, as distinguished from equalising opportunities or treatment. Public authorities cannot discriminate to achieve proportional representation of groups in outcomes. Laws and policies must be neutral regarding outcomes, judged by whether they remove illegitimate barriers rather than whether they produce statistical parity. This liberty permits addressing genuine discrimination and removing unjust obstacles whilst forbidding racial quotas, gender balancing requirements, and similar measures treating people differently to achieve equalised results.

The second chapter addresses speech and expression freedoms. Freedom from compelled speech prevents authorities from requiring persons to express beliefs they do not hold, make statements supporting ideologies they reject, or participate in symbolic acts contrary to conscience. Examples include required affirmations of ideological propositions, compulsory use of preferred pronouns contrary to biological reality, mandatory participation in political rituals, and similar impositions. The liberty protects the right to silence and the right to dissent from official orthodoxies. Exceptions permit requiring factual disclosures for legitimate regulatory purposes, such as product ingredients, health warnings, or financial disclosures, but not compelled expressions of belief or opinion.

Freedom from censorship prevents governmental suppression of speech, publication, or expression based on content. Public authorities cannot prohibit, penalise, or restrict expression because of disagreement with the ideas expressed. This liberty protects political speech most strongly, recognising that democratic self-governance requires robust debate including speech offensive to prevailing sensibilities. It extends to artistic, literary, scientific, and religious expression. Narrow exceptions permit restrictions on true threats, incitement to imminent violence, defamation, fraud, obscenity involving children, and similar historically recognised categories where speech itself constitutes harm. The liberty does not extend to conduct, only expression. Governments may regulate the time, place, and manner of expression through content-neutral rules but cannot discriminate based on viewpoint.

Freedom from indoctrination prevents educational and governmental institutions from using their authority to inculcate ideological beliefs in captive audiences, particularly children. Schools may teach facts, skills, and cultural knowledge but must not propagandise for contestable political or philosophical positions. Teachers may present multiple perspectives on controversial questions but must not impose their views as orthodoxy. This liberty particularly protects children from manipulation during their formative years whilst acknowledging legitimate educational objectives.

The third chapter addresses bodily autonomy. Freedom from medical coercion prevents governmental mandates for medical interventions absent genuine public health emergencies. Persons retain authority over their own bodies, including rights to refuse testing, treatment, or prevention. Vaccines, pharmaceuticals, and other interventions cannot be mandated generally, though narrow exceptions permit quarantine and isolation during genuine epidemics of highly dangerous communicable diseases. The liberty prevents authoritarian public health measures whilst preserving legitimate disease control powers for extraordinary circumstances.

Freedom of biological immutability recognises biological sex as an immutable characteristic determined by reproductive anatomy and function. Legal recognition and social facilities may not be allocated based on self-declared gender identity in circumstances where biological sex is material. Single-sex spaces including bathrooms, changing rooms, hospital wards, prisons, and similar facilities may exclude persons of the opposite biological sex regardless of gender identity. Sporting competitions may establish categories based on biological sex. Birth certificates and similar official documents record biological sex rather than gender identity. Medical treatment may not alter the bodies of children or adolescents based on gender identity distress. The liberty acknowledges biological reality whilst permitting adults to make choices regarding their own lives.

Freedom of biological separateness prohibits governmental facilitation of the creation of human-animal hybrids, human clones, or genetically modified humans. Genetic engineering of human embryos is forbidden except for correcting defects causing serious disease. Human reproduction must proceed through natural biological processes, not technological manipulation. This liberty reflects human dignity and prevents horrors reminiscent of eugenics programmes.

The fourth chapter addresses personal dignity and privacy. Freedom of obscurity, also known as the right to be forgotten, enables persons to remove personal information from public databases, commercial records, and governmental archives after sufficient time has passed. Exceptions protect legitimate historical research, ongoing legal proceedings, and public interest in serious crimes, but ordinary persons may escape permanent digital surveillance by demanding removal of outdated personal data. This liberty responds to the permanence of internet records and commercial data collection.

Freedom from malicious commercialisation prevents commercial exploitation of personal data, images, or likenesses without meaningful consent. Corporations cannot harvest and sell personal information gathered through digital services without explicit opt-in permission. Surveillance capitalism practices requiring users to surrender privacy as the price of accessing essential services violate this liberty. Persons retain property rights in their own data and must receive fair compensation for commercial use.

Freedom from mass surveillance prohibits governmental or corporate systems conducting indiscriminate monitoring of populations. Specific targeted surveillance of individuals suspected of serious crimes remains permissible with proper warrants, but dragnet collection of communications, movements, transactions, and activities violates this liberty. Mass CCTV networks, automated number plate recognition, facial recognition systems, and similar technologies require strict limitation to prevention of serious crime with appropriate safeguards. The liberty preserves space for private life beyond governmental observation.

The fifth chapter addresses historical and social matters. Freedom from historical guilt prohibits imposing collective guilt, shame, or liability on persons for actions of others in the past. No person bears responsibility for historical injustices committed by others, whether ancestors, co-ethnics, or members of the same nation. Educational and governmental institutions may teach history accurately including uncomfortable truths but must not assign guilt or demand expiation from present persons for past wrongs. Reparations, collective apologies, and similar practices treating people as representatives of historical groups rather than individuals violate this liberty.

Freedom from serious immigration crime protects persons from crimes committed by individuals whose presence in Britain results from governmental immigration policies. The liberty recognises governmental duty to protect citizens from violent crime and establishes liability when authorities permit entry of dangerous individuals who subsequently cause serious harm. This provision enables civil actions against governmental immigration authorities when their negligence or recklessness in vetting, monitoring, or removing dangerous aliens results in murders, sexual offences, or other grave crimes. It aims to incentivise careful immigration management and provide remedy to victims.

The sixth chapter addresses emerging technological concerns. Freedom from automation prevents replacement of human judgment with algorithmic decision-making in sensitive areas including criminal sentencing, medical diagnosis, welfare eligibility, and educational assessment. Automated systems may assist human decision-makers but cannot substitute for human judgment in matters significantly affecting persons' rights, opportunities, or welfare. This liberty preserves human dignity and accountability whilst permitting beneficial uses of technology where appropriate.

Each liberty receives precise definition specifying scope, permissible limitations, enforcement mechanisms, and remedies for violations. The enforcement occurs through ordinary courts without specialised tribunals or administrative bodies, preserving separation of powers and preventing proliferation of bureaucracy.

Part 10: Westminster Palace and Ceremonial Functions

This Part addresses the future of Westminster Palace after Parliament relocates, structured across four chapters concerning ceremonial use, educational functions, diplomatic training, and the Institute of Statesmanship.

State Opening of Parliament continues at Westminster annually, maintaining connection with tradition and history. The monarch proceeds in state from Buckingham Palace to Westminster, entering through the Sovereign's Entrance, proceeding to the historic House of Lords chamber where the Speech from the Throne is delivered. Members of the Lower House are summoned by Black Rod, preserving the ancient ritual symbolising parliamentary independence. The ceremony occurs in Westminster despite Parliament's ordinary business occurring in Derbyshire, recognising the importance of tradition and the unsuitability of conducting such grand ceremony in a working parliament building.

Royal weddings, funerals, and coronations continue using Westminster Abbey adjacent to the palace complex, maintaining the historic connection between Crown and Westminster. Lying in state for deceased monarchs and distinguished persons may occur in Westminster Hall as historically practised.

Educational programs transform Westminster into a living museum of parliamentary government. School groups tour the historic chambers, learning constitutional history in the rooms where it unfolded. Interactive exhibits explain how Parliament functions, the development of democracy, and Britain's constitutional evolution. Historical reenactments in the chambers bring the past to life. University programs use Westminster facilities for teaching politics, history, and constitutional law. International visitors study British parliamentary traditions, with Westminster serving as an exemplar of stable democratic governance.

The British Diplomatic Institute occupies portions of Westminster Palace, training future diplomats in historic surroundings. The institute operates as a residential academy offering intensive 12-month programs to approximately 100-150 students annually, combining recent Foreign Office entrants, mid-career diplomats upgrading skills, international fee-paying students building relationships with British counterparts, and military officers receiving joint military-diplomatic training. Faculty comprise retired ambassadors, academic experts, serving diplomats on secondment, and international guest lecturers. The curriculum covers diplomatic history and tradition, international law, negotiation and mediation, cultural intelligence, intensive language training, economic diplomacy, public diplomacy, crisis management, and intelligence overviews. Practical training includes simulations, negotiations exercises, crisis scenarios, model UN assemblies, and diplomatic protocol training. The Westminster setting provides inspiration and prestige, with students learning in chambers where great diplomats worked, accessing historic portraits and documents, and absorbing British diplomatic tradition. International students, approximately 20-30 per cohort paying substantial tuition, return to their countries as Anglophiles and British partners, spreading understanding of the British approach whilst building networks among future diplomatic leaders globally.

The British Institute of Statesmanship provides dignified roles for former senior politicians and civil servants whilst contributing to policy research and constitutional scholarship. Twenty to thirty fellows serve two to five year renewable terms, selected by invitation from former Prime Ministers, Cabinet Ministers, Permanent Secretaries, Governors of major territories, and military chiefs. Fellows conduct major policy studies leveraging decades of governmental experience, addressing challenges including constitutional reform, economic strategy, international relations, territorial expansion strategies, and technology and governance. They study and document British constitutional tradition, write histories and analyses, contribute to constitutional debates, and preserve institutional memory. Mentoring current ministers and senior civil servants provides channels for wisdom transfer without interference in executive functions. Fellows write memoirs, histories, and analyses published by the institute, contributing to public understanding. Guest lectures at universities, teaching at the Diplomatic Institute, and public lectures at Westminster extend their influence. The government may consult fellows informally during major challenges or crises, drawing on experience without creating formal advisory bodies. Fellows become available for international mediation, represent Britain at conferences, and build relationships with foreign elder statesmen, exercising soft power and influence. This arrangement retains expertise otherwise lost to retirement, provides dignified roles better than corporate boards, preserves institutional memory, contributes to policy quality, and enhances British intellectual capital at modest cost.

Part 11: Financial and Budgetary Arrangements

This Part establishes detailed fiscal procedures across four chapters addressing parliamentary finance, territorial contributions, money bills, and audit mechanisms.

Parliamentary budgets receive independent determination through statutory bodies insulated from executive manipulation. The Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority for the Lower House and equivalent bodies for each upper house assess operational needs, determine appropriate remuneration, allocate resources for offices and staff, and present budgets to Parliament for approval. Once approved, these budgets cannot be reduced by the executive branch, preventing financial coercion. Members receive salaries reflecting the importance and demands of their offices whilst avoiding excess that might alienate voters or encourage rent-seeking.

Territorial contributions follow the exhaustive formula in Schedule 15, calculating each territory's share of central government costs based on population, GDP, and fiscal capacity. Wealthier territories contribute proportionally more, recognising both ability to pay and greater benefit from common services including defence and currency stability. Less developed territories contribute modest amounts, avoiding crushing burdens whilst maintaining the principle of shared responsibility. The formula adjusts automatically as territories develop economically, ensuring fairness across time. Revenue sharing returns portions of nationally collected taxes including income tax, VAT, and corporate tax to territories according to population-weighted formulas, providing resources for devolved functions. Development grants supplement revenues in less developed territories, enabling infrastructure investment, education improvement, and economic advancement. The fiscal arrangements aim for rough equity, where territories contribute fairly whilst receiving adequate resources for legitimate needs.

Money bills follow historic procedures, originating exclusively in the Lower House. The Speaker certifies bills imposing taxes or authorising expenditure as money bills, triggering special procedures. Upper houses receive money bills for 30-day consultation periods, reviewing and offering advisory opinions without power to reject or amend. This preserves the constitutional principle of Commons financial supremacy, preventing unelected or indirectly elected upper houses from controlling taxation. The Lower House may accept upper house suggestions but is not bound. Money bills proceed to Royal Assent after consultation periods expire regardless of upper house views.

Territorial finances require transparency and accountability. All budgets, revenues, expenditures, transfers, and grants appear in published accounts accessible to citizens. Online portals enable detailed scrutiny of how governments spend public money, down to individual transactions above de minimis thresholds. This transparency deters corruption, enables informed electoral choices, and facilitates comparison of efficiency across territories.

Audit occurs through the National Audit Office examining all parliamentary and governmental accounts annually. Independent auditors verify accuracy, assess efficiency and effectiveness, evaluate value for money, and identify waste, fraud, or abuse. Published audit reports receive parliamentary scrutiny through Public Accounts Committees examining findings and recommending corrective action. Upper houses receive separate audits recognising their independence, with reports submitted to the respective chambers. Parliamentary Standards Authorities investigate allegations of financial impropriety by members, conducting inquiries and imposing sanctions including repayment of inappropriate expenses, suspension, or expulsion for serious violations. Criminal prosecution remains available for frauds or thefts.

Part 12: Constitutional Amendment Procedures

This Part establishes entrenchment mechanisms protecting the constitution's fundamental features whilst permitting evolution, structured across three chapters addressing constitutional fundamentals, amendment procedures, and popular participation.

Constitutional fundamentals receive specific enumeration, distinguishing them from ordinary provisions subject to simpler amendment. These fundamentals include the existence of the Britannic Parliament itself, the four-nation structure comprising England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, the monarchy and Crown's constitutional role, the Lower House composition principle of population-weighted representation, the national upper houses with one per nation, the round-robin revision system for legislation, the division between reserved and devolved matters, natural liberties protections, the territorial representation system, and the geographic location of Parliament at the centroid. These fundamentals constitute the constitution's core identity, requiring stringent procedures for amendment.

Amendment of fundamentals requires a two-thirds majority in the Lower House, ratification by three of four national upper houses (75 per cent), and national referendum for specified matters. Referendum is mandatory for abolishing the monarchy and establishing a republic, secession of any nation, abolition of the Britannic Parliament, removal of core natural liberties, and other matters the Lower House designates by two-thirds vote. Referendums require simple majority (50 per cent plus one) of votes cast with minimum turnout of 40 per cent of registered electorate. Campaign periods last between 12 and 26 weeks, with fair broadcasting rules ensuring balanced coverage, spending limits preventing plutocratic domination, and transparency requirements disclosing campaign funding sources. The amendment procedure extends over a minimum 12 months from introduction to enactment, passing through multiple stages including proposal, first vote in Lower House, upper house ratification, referendum where required, and final vote. Royal Assent follows completion of all stages.

Amendment of ordinary provisions, encompassing all constitutional matters not listed as fundamentals, requires 60 per cent majority in the Lower House (simple majority plus 10 percentage points), consultation with upper houses permitting non-binding input, and no referendum requirement. Upper houses may propose amendments or express opposition, with the Lower House free to accept, modify, or reject suggestions. The procedure requires minimum three months from introduction to enactment, balancing accessibility with deliberation. Examples of ordinary provisions include specific boundary details, procedural rules, administrative arrangements, and technical specifications capable of adjustment without threatening constitutional fundamentals.

Entrenchment operates through express repeal requirements, preventing implied repeal of constitutional provisions. Future Parliaments cannot inadvertently override the constitution through legislation inconsistent with it. Constitutional amendment must follow prescribed procedures, binding subsequent Parliaments through manner and form requirements recognised in Commonwealth jurisprudence. The Parliament Act procedures do not apply to constitutional amendments, preventing circumvention of upper house involvement through declaring deadlock. This entrenchment gives the constitution higher legal status than ordinary legislation, creating constitutional supremacy to the extent constitutional fundamentals cannot be changed casually.

Popular participation through referendum for fundamental changes recognises that the constitution ultimately rests on popular consent. Whilst Parliament possesses legislative supremacy within constitutional bounds, changes to constitutional fundamentals require direct popular approval. This prevents political classes from making radical changes without explicit authorisation, ensuring the constitution reflects settled popular will rather than temporary parliamentary majorities or elite preferences.

Part 13: Final Provisions, Commencement, and Schedules

This Part addresses technical matters across three chapters concerning interpretation, commencement, and general provisions.

Interpretation provisions establish how terms and phrases receive meaning throughout the Act and in subsequent legislation referencing it. Schedules possess equal legal force to main provisions, establishing binding rules rather than mere guidance. Welsh language translations possess equal status for Welsh matters, ensuring linguistic equality in Wales. Gaelic and Irish translations are available but English texts remain authoritative, recognising practical necessity whilst respecting linguistic heritage.

Judicial review permits courts to review governmental compliance with the Act, including challenges to override exercises as potentially ultra vires, challenges to tier classifications, determination of reserved versus devolved disputes, and interpretation of constitutional provisions. The existing constitutional court arrangements continue, with minor adaptations for the new structure. A presumption in favour of devolution applies where language is ambiguous, interpreting uncertainties to favour autonomy rather than centralisation.

Commencement occurs in phases specified in Schedule 1. Sections 1 through 4 and Part 13 take effect upon Royal Assent, establishing the Act's status and interpretive framework immediately. Site selection provisions commence within six months, beginning the process of locating and acquiring land for the new Parliament. Natural liberties provisions become immediately effective, ensuring rights protections are in place before HRA repeal. Abolition provisions take effect on 1 April of Year 11, dissolving the House of Lords, Scottish Parliament, Welsh Senedd, Northern Ireland Assembly, and all local authorities simultaneously. Full parliamentary operation commences in Year 13, with the Lower House and all upper houses functioning under the new arrangements. Detailed commencement schedules specify effective dates for each provision, enabling orderly transition. The Secretary of State may make commencement orders for phased provisions where gradual implementation proves desirable.

Extent provisions establish the Act's geographic application. The Act extends to England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, applying throughout the United Kingdom. It extends to all British Overseas Territories, bringing them under the new constitutional framework. It extends to all Crown Dependencies, incorporating Jersey, Guernsey, and the Isle of Man. It extends to all territories acquired under Part 5, ensuring universal application of constitutional principles across expanded British domains.

The short title permits citation as the Britannic Parliament Act 2025, providing a concise reference for this transformative constitutional statute.

The 23 schedules provide exhaustive detail on matters requiring precision beyond the main text.

- Schedule 1 establishes the 13-year commencement timetable with year-by-year milestones.

- Schedule 2 contains the complete text of the 15 natural liberties with detailed definitions and limitations.

- Schedule 3 specifies ECHR withdrawal procedures including denunciation timelines and transitional arrangements.

- Schedule 4 lists all current territories with populations, tier classifications, and seat allocations.

- Schedule 5 specifies Lower House constituency boundaries with mathematical precision.

- Schedule 6 details round-robin procedures including flowcharts and timelines.

- Schedule 7 establishes transitional arrangements for the Upper House of England.

- Schedule 8 provides procedures for establishing territorial upper houses.

- Schedule 9 defines tier classification criteria and advancement procedures.

- Schedule 10 presents the territorial representation formula.

- Schedule 11 exhaustively lists reserved matters by category.

- Schedule 12 exhaustively lists devolved matters.

- Schedule 13 provides constitutional provisions for each territory, including governance structures, powers and duties, electoral systems, rights protections, judicial arrangements, amendment procedures, and transition provisions.

- Schedule 14 establishes staff transfer provisions from abolished institutions to successor bodies.

- Schedule 15 specifies territorial fiscal arrangements including contribution formulas and revenue sharing.

- Schedule 16 details planning and construction timelines for the new parliamentary complex.

- Schedule 17 establishes Westminster Palace preservation and ceremonial use procedures.

- Schedule 18 provides provisions for the British Diplomatic Institute and Institute of Statesmanship.

- Schedule 19 addresses local government staff transfers, redundancies, and compensation.

- Schedule 20 contains transition provisions ensuring all existing law continues in force.

- Schedule 21 establishes international conference procedures.

- Schedule 22 provides consequential amendments to thousands of existing Acts updating terminology and references.

- Schedule 23 lists repealed Acts completely superseded by new arrangements.

The cumulative effect of these schedules transforms the skeleton into a comprehensive legal code governing every aspect of the constitutional transformation, ensuring no detail is overlooked and no ambiguity remains unaddressed.