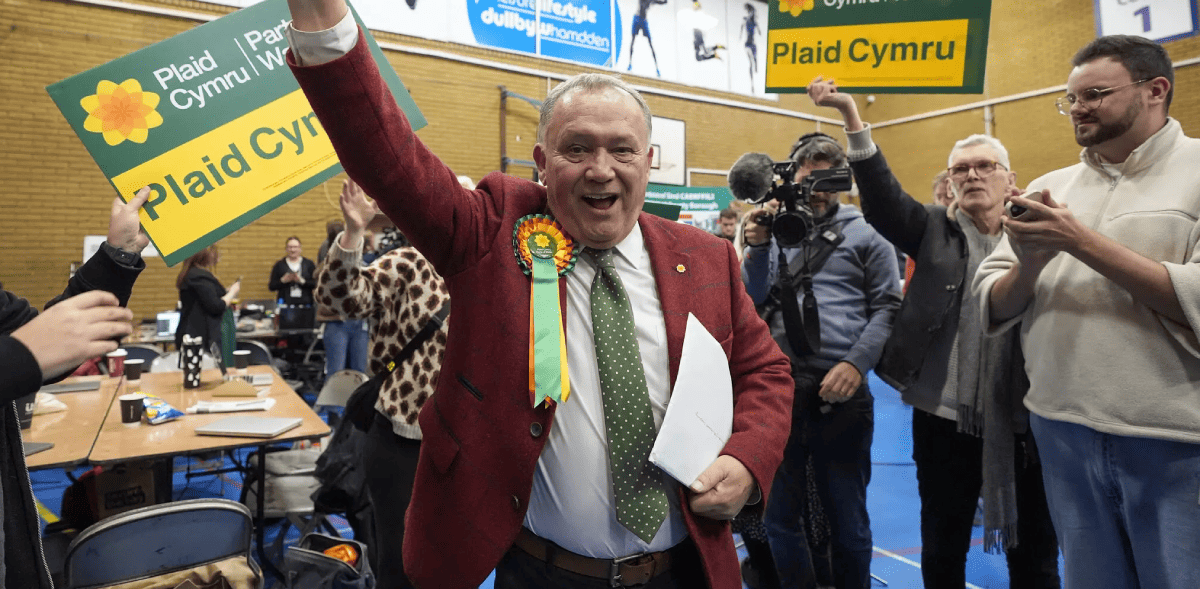

Time To Face Up To The Widespread Failure Of Devolution

Welsh devolution has always rested on a false democratic foundation. A quarter of a century on, the record speaks plainly: it has failed. Although the mandates elsewhere were different, the results were the same. The time has come to face the fact and bring it to an end.