Understanding The ECHR, HRA, Devolution, and Good Friday Agreement

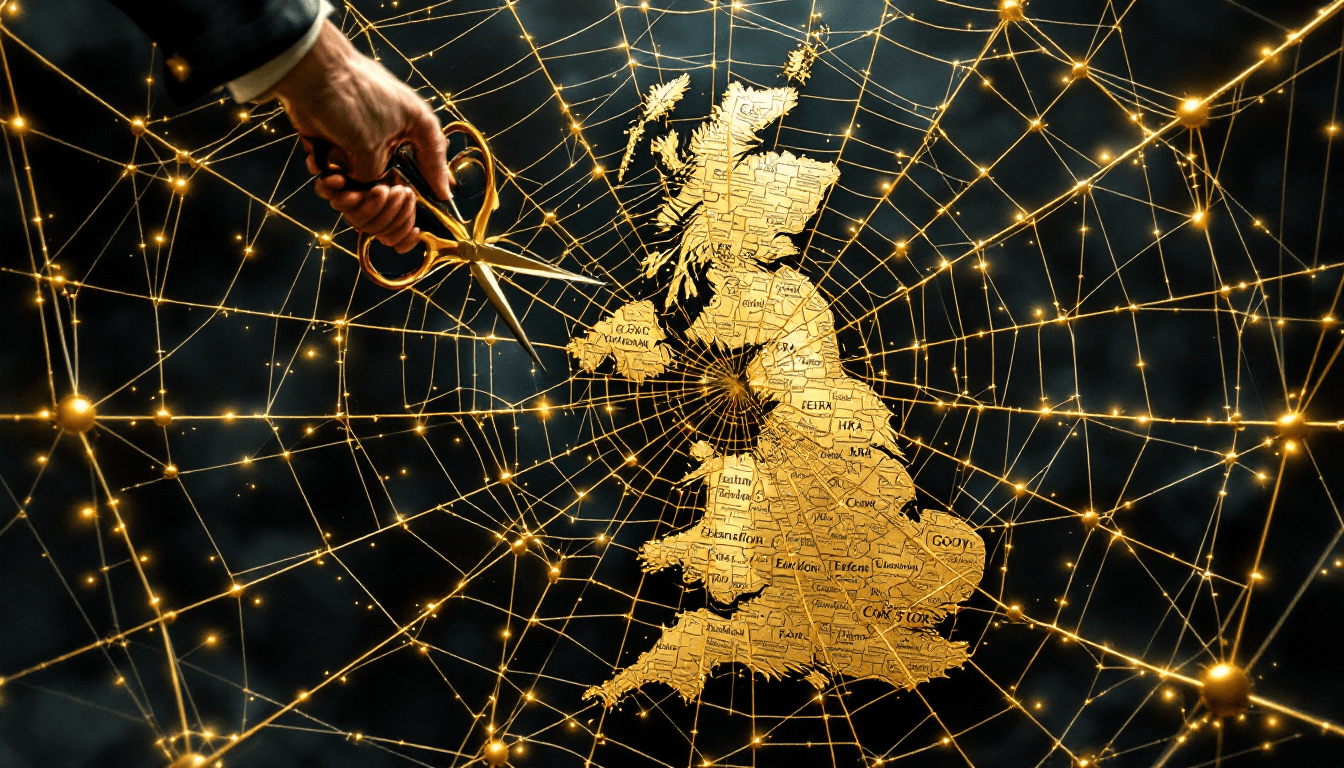

Britain's need to "just leave" the European human rights system reveals a constitutional puzzle of extraordinary complexity. What appears simple on paper becomes labyrinthine in practice - a quarter-century web designed to defy easy untangling.