What Is A Superinjunction?

British judges can secretly gag legal proceedings and ban reporting their very existence. Revealing that a superinjunction exists can itself be contempt of court, creating invisible censorship where the public cannot know what they're forbidden to discuss.

In a putative, English-speaking democracy, one might imagine that justice is not only done, but seen to be done. One would be quite wrong. Among the most sinister legal mechanisms lurking in the shadowed corridors of British public life is the superinjunction. This is where a judge files away papers in a drawer and orders no-one is allowed to say he did.

A superinjunction is a way of making sure you, the public, never know something in court ever happened. Or anyone covered it up. It's a cover-up, of the cover-up.

This is a gag so potent, so hermetically sealed it would make Richard Hermer KC himself blush. The very existence of such a gagging order cannot even be reported. These are not merely instruments of privacy but judicially sanctioned cloaks of invisibility, a veil so impenetrable it cannot be discussed. They are frequently deployed by the powerful to suppress not only inconvenient truths, but also, the fact of suppression itself.

And yet, they endure and continue in their use today. So much for the whiggish conception of our march towards a glorious present. They are granted by our courts, serviced by wealthy law firms, and increasingly wielded to conceal matters of real national consequence and risk to the public. Not least among these is the government’s quiet, court-backed facilitation of Afghan resettlement and related immigration policies.

All causes ought to be heard, ordered and determined before the judges of the king's courts openly in the king's courts, whither all persons may resort. - Daubney v Cooper (1829)

Before confronting the rot at the core, let us define the terms of the pathology.

What Even Is An Injunction?

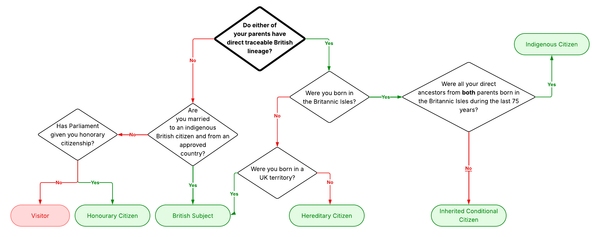

An injunction is a court order compelling a party either to act or to refrain from acting. In practice, such orders often prevent the disclosure or repetition of allegedly harmful or unlawful conduct. This includes, for instance, publication of defamatory material or the leaking of confidential documents. Injunctions can be interim (temporary, pending fuller hearing) or final, depending on the stage of litigation.

In the UK, injunctions are normally governed by the Civil Procedure Rules, especially Part 25. They are sought on grounds such as breach of confidence, misuse of private information, or defamation. In deciding whether to grant injunctive relief, judges must balance an applicant’s Article 8 rights (to private and family life) against the respondent’s Article 10 rights (freedom of expression), under the Human Rights Act 1998.

So far, so comprehensible. But then we meet the darker cousin, unbound by the inconsequence of the Human Rights Act: the superinjunction.

What Makes It “Super”?

A superinjunction does more than merely prevent publication of sensitive material. It prohibits anyone from reporting an injunction has been granted at all. The press, the public, even the larger discourse outside the shield of privilege, are rendered mute.

By contrast, there are (still pernicious) lesser forms:

- Anonymised injunctions block publication of content but permit mention of the injunction itself, with anonymised parties, as in PJS v NGN.

- Norwich Pharmacal orders compel third parties, often internet platforms, to reveal identities of leakers or intermediaries.

But the superinjunction is unique in its double cloak. It conceals not just the secret, but the act of secrecy itself. It is, in full measure, the judicial equivalent of a black site.

Where Are Superinjunctions Kept?

In the United Kingdom, super-injunctions are issued by the High Court, most often within the King’s Bench Division in the Media and Communications List. The orders and all related records are kept on the sealed court file, accessible only to the parties involved, their legal representatives, and the judge. Judges may occasionally circulate anonymised internal summaries to colleagues to avoid conflicts between orders, but the documentation is not available to the public.

Unlike ordinary injunctions, which are frequently published on the British and Irish Legal Information Institute (BAILII) or in the official law reports—sometimes anonymised with titles such as XYZ v Persons Unknown—super-injunctions are not published at all while they are in force.

In some cases, once a super-injunction has lapsed, been discharged, or varied, the courts have chosen to release anonymised judgments, which then appear retrospectively on BAILII.

In practice, the only official storage of these orders is on sealed High Court files. They sometimes become more widely known through foreign reporting, leaks, or the use of Parliamentary privilege, but these are exceptions that fall outside the formal system. Officially, until the court decides otherwise, super-injunctions remain completely confidential.

Legal Basis & Judicial Complicity

Superinjunctions emerge from the same judicial ecosystem that produced modern privacy law. This is a jurisprudential overlay grafted onto traditional breach of confidence law, given new life after Campbell v MGN Ltd [2004] UKHL 22, with its balancing of Articles 8 and 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights. The use of superinjunctions proliferated in the late 2000s, abetted by High Court judges keen to conform to European norms rather than to uphold deeper strands of English common law.

"The press and public have a right to receive information about judicial proceedings" - Article 6 ECHR principle established in multiple ECtHR cases

The legal justification for superinjunctions typically lies in a claim of imminent, serious harm. This may be emotional or reputational, sometimes even existential. But the threshold for “harm” is nebulous, elastic, and too often defined by the claimant’s lawyers rather than any principled standard. Harm, like violence, has become a weasel word.

Those lawyers who master the weasel-word are handsomely rewarded.

The Industry of Silence: Carter-Ruck & Co.

No discussion of superinjunctions is complete without naming the professional silencers: Carter-Ruck. Over decades, this London firm has fashioned a reputation for rendering secrets discreet. In 2009, Carter-Ruck obtained an injunction for Trafigura to suppress reporting on toxic waste dumping in the Ivory Coast. Audaciously, they extended the gag to include parliamentary proceedings.

Only after an online moral uproar did the press break through the barrier. This proved that superinjunctions are both futile and disgraceful. But the legal fees were already paid, and the press had unwittingly advertised the practice itself.

Other firms, including Schillings and Mishcon de Reya, are equally complicit. They do not simply act as neutral service providers to clients. They are ideological operators, deploying “reputation management” and “privacy” as veneers for suppression. Their clients are typically the ultra-wealthy, powerful, or compromised. That, however, is incidental. To them, laundering inconvenient truths is a line of business. The only conflict is if the cheque bounces.

Afghan Resettlement Superinjunction

Here we confront the most unconscionable development. Superinjunction-style devices have been used to shield government policy and action on immigration from democratic scrutiny. These include total publication bans, anonymity orders, and procedural redactions. This is not theoretical.

In multiple recent instances, judges have prohibited reporting on Afghan relocation programmes, national security vetting, and even opposition by local authorities to resettlement schemes. Reporting restrictions can cloak entire hearings. Ministers speak only in vague euphemisms about “safe relocation.” NGOs bring claims to override local planning law. Meanwhile, the public is told nothing – lest they object to demographic change being orchestrated without their knowledge, much less their consent.

The scale of the UK’s Afghan relocation programmes is now material. Official Immigration System releases and parliamentary briefings record tens of thousands of people moved to the UK under the bespoke Afghan routes. By mid-2025 some 35,700 people had been resettled or relocated under the main Afghan schemes (ARAP and ACRS), with total arrivals from the evacuation exercise somewhat higher (c.38,700 to the end of June 2025 in published operational datasets).

A further, separate cohort was created after a Ministry of Defence data breach in 2022. The NAO found the MoD treated the breach as a national-security emergency and established a secret Afghanistan Response Route (ARR).

The superinjunction was granted “contra mundum”, meaning “against the world”, by the courts, and is enforceable against anyone who knows about it, rather than a named party.

The NAO reports 7,355 people were identified as eligible under the ARR; by June 2025 only 3,383 of those eligible had actually arrived, although subsequent reporting has suggested the pool affected by the breach could be substantially larger. The NAO criticised the secrecy surrounding the scheme and the MoD’s failure to track costs properly.

Family units and dependants are a significant part of these totals: both ARAP and ACRS explicitly include family members in their definitions of beneficiaries, and Home Office funding documents and scheme guidance use the term “additional family member” when setting entitlements and funding provision. In practice that has meant some principals arrived with multiple dependants and some cases — reported in the national press and to Parliament – where extended family groups were allowed in.

Media investigations and parliamentary material have cited extreme cases of a principal bringing more than a dozen relatives (one outlet reported up to 22 in isolated examples), but there is no single official published “dependants per principal” average from the Home Office which converts these headline cases into a stable multiplier.

The Home Office’s operational data gives us headline arrival totals, and the NAO exposes serious governance problems around one high-profile response route. But there is no comprehensive, independently audited dataset publicly available that links individual resettled status, household composition, length-of-stay and later offending with the methodological rigour required to prove causal links between resettlement and types of crime.

The vacuum of reliable, transparent information is precisely why secrecy is dangerous in the context of the mass-import of war-trained Afghans and their extended families (clans): it allows ministers and administrators to manage politically sensitive population change under legal and journalistic blackout, while the public is left to trade in rumour, selective press examples and partisan claims.

A Pattern of Evasion

Some key cases exposing the architecture of secrecy include:

- Trafigura v The Guardian (2009), where lawyers sought to block reporting on a parliamentary question via superinjunction.

- John Terry obtained one in 2010 about an affair with an ex-girlfriend of his former Chelsea team-mate Wayne Bridge.

- Journalist Andrew Marr also took out a controversial superinjunction in 2011 over an extramarital affair.

- CTB v News Group Newspapers Ltd (2011), where attempts were made to suppress the naming of Ryan Giggs, despite eventual intervention by Parliament.

- PJS v NGN Ltd [2016] UKSC 26, where the Supreme Court upheld an anonymity injunction, even after widespread online publication.

- ABC v Telegraph Media Group [2018] EWCA Civ 2329, which delayed exposure of serious misconduct by a business figure using NDAs and privacy orders.

- Family-division cases from 2021 to 2024, involving Afghan resettlement and asylum decisions. These were anonymised, redacted, and injuncted so severely anyone even acknowledging their existence risks contempt.

Keir Starmer himself is the subject of innumerable rumours of superinjunctions, none of which have been proven but illustrate the suspicion they cause:

- Alleged romantic involvement with Labour donor Lord Waheed Alli, tied to gifted clothing, accommodation, and £100k+ in undeclared donations.

- Whispers of an undisclosed "love child" or hidden family members (e.g., more than his known two sons).

- Involvement with rent boys from Ukraine, possibly linked to aid policies or advisors.

- Hiding reasons for suspending ex-Labour chief whip Nick Brown in 2022 over "serious criminal allegations."

- Details of Rayner's property sales and tax avoidance claims during 2024 election.

The mere existence and persistence of these rumour chains in public discourse is enough to furnish the point they sully trust in public officials and the accountability of government.

The Death of Parliamentary Privilege

It is often said that the health of a democracy may be gauged by the speech permitted in its Parliament. If so, Britain’s democracy is comatose.

The supposed constitutional safeguard of Parliamentary Privilege, enshrined in Article 9 of the Bill of Rights 1689, once protected MPs’ freedom to speak in Parliament without fear of “impeachment or question in any court.” It was designed to keep both judiciary and Crown from muzzling elected representatives. Like many English liberties, it has been hollowed out by precedent, practice, and institutional timidity.

The erosion began in 1844, when Erskine May’s procedural guide introduced the notion of “unparliamentary language” – a euphemism for curbing blunt challenge. In 1888, the Speaker was given the power to suspend MPs for disorderly conduct. This tool has long since been used to suppress dissent. By 1963, the sub judice rule banned MPs from referring to ongoing court cases, fitting a legal muzzle directly onto the legislature.

Decay quickened under John Major, who codified parliamentary conventions. Blair expanded them, forcing ministers to defer to “independent advisers.” Managerialism triumphed over sovereignty.

From 2020 to 2021, MPs were effectively suspended from meaningful debate under the Coronavirus Act. Parliament became a Zoom show. In 2024, following the Southport stabbings, the pretence collapsed completely. MPs were explicitly barred from asking questions about the case, under threat of contempt.

In a chamber supposedly immune from judicial interference, speech is now vetted by lawyers before it reaches Hansard. This is not mere decay – it is reversal. The institution once built to protect speech now muzzles itself. Into that void steps the superinjunction, to muzzle discussion of entire people, or areas of policy.

Outrage, Reform, and the Future of Open Justice

Superinjunctions have not disappeared. They have merely changed form. After the 2011 reforms and Lord Neuberger’s modest guidelines, the practice morphed into reporting-restriction orders with anonymity provisions. The name changed, but the substance remains.

Open justice is a fundamental aspect of the way in which courts in England and Wales administer justice. - Lord Neuberger

Judicial discretion is supposed to contain their reach. But in practice, judges under pressure from lawyers, state actors, or security officials, often capitulate. The principle of open justice is subordinated to institutional caution.

The concentration of silence remains where it always has – in the hands of the rich and powerful. Foreign oligarchs, state interests, political networks, resettlement operatives – all keep the silencers on retainer.

It is a fundamental principle that justice should not only be done, but should manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done. - Lord Chief Justice Hewart in R v Sussex Justices, ex parte McCarthy [1924]

To understand superinjunctions is to perceive a deeper rot. Secrecy now supplants sovereignty. Fear replaces democratic discourse. What began as a rare shield for privacy has become a sword for manipulation and deceit.

No country that hides its immigration policy behind court orders deserves to call itself free. And no people who tolerate such concealment can claim to govern themselves. People still believe net immigration nis in the tens of thousands – wrong by two orders of magnitude, as touched upon here. It is therefore more important than ever for the public to be aware of their situation.

The hearing of a case in public may be, and often is, no doubt, painful, humiliating or deterrent both to parties and witnesses, and in many cases, especially those of a personal character, the requirements of open justice will to some extent defeat the remedy which the court intends to provide. But all this is tolerated and endured, because it is felt that in public trial is to be found, on the whole, the best security for the pure, impartial and efficient administration of justice, the best means for winning for it public confidence and respect. - Scott v Scott [1913] AC 417 (House of Lords)

We do not live in a rich country, nor a free country. England is under attack, from all sides and within, and the intention of everything from the Online Safety Act (2023) to the jurisprudence surrounding superinjunctions aims to keep it that way – and – ensure you are blissfully unaware of the predicament you are in.