What Is An Englishman?

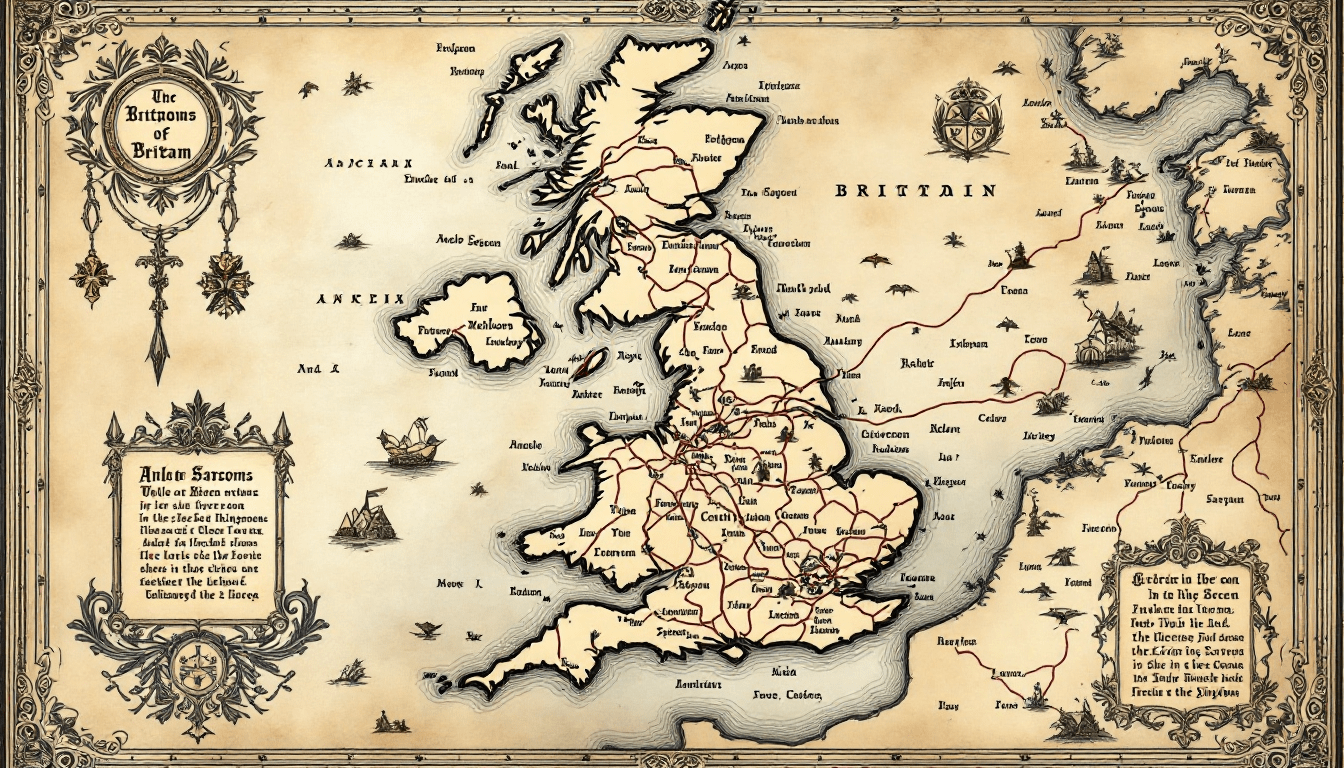

The English ethnic group traces its origins to 5th-century Germanic migrants who integrated with native Britons. Modern genetic studies confirm English people, first documented by Bede in 731 AD, are today 25-47% Anglo-Saxon.

The English ethnic group traces its origins to 5th-century Germanic migrants who integrated with native Britons. Modern genetic studies confirm English people, first documented by Bede in 731 AD, are today 25-47% Anglo-Saxon.

Integrity is not negotiable. Even in our most difficult moments, we must hold the people closest to us accountable, even if it shocks us to the core. No compromise with evil. No compromise with the darker secrets hidden away. This spectre came to haunt us this week with devastating consequences.

Nothing exposes middle-class Marxist racism like an actual tragedy. While students chant death to Israel in support of murderous Islamic rapists, innocent Christians are butchered by the hundred-thousand by Muslim fanatics. Nobody cares. Because it's Africa, and they're poor, rural, and black.

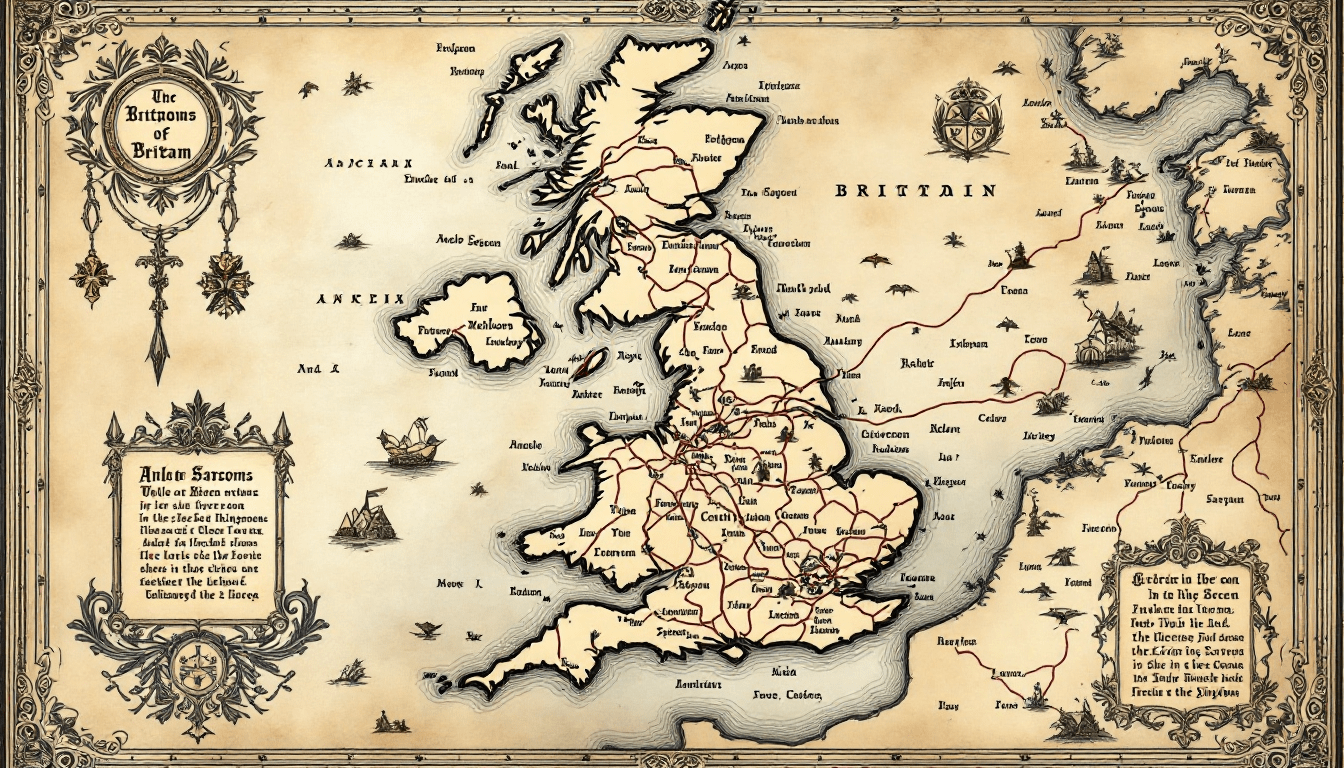

The American 1863 Abraham Lincoln national holiday of Thanksgiving, similar to the 1843 Harvest Festival in England, emerged from the celebration of Guy Fawkes Night of November the 5th and the Puritans' arrival to the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1619. Remember, Remember, the Fifth of November...

MPs across parties publicly support a rape gangs inquiry but write no legislation to create one. This bill establishes a statutory inquiry with compulsory powers, protected funding, and a nine-month timeline to deliver answers instead of Instagram selfies and PR gimmicks. Do your damned job.